Liveaboard Diving in Belize's New Shark Sanctuaries

My entire body convulses as I turn to find a shark headed directly at me. It’s only feet away, gray flesh shining in the filtered sunlight, pupils growing larger as the dark edges of its fins come into focus. Through my sudden heart attack, I see this Caribbean reef shark is barreling ahead like a determined New Yorker crossing the street. It has no intention of changing course—it’s swimmin’ here.

Alexandra GillespieA Caribbean reef shark soars past the author.

I shouldn’t be so shocked—I’d already watched sharks pacing along the reef wall this very dive—but I am. You think of large animals making a noise as they move, a rustle of leaves or the creak of a branch. But that’s not the case underwater. A shark’s approach is silent. There is no ominous soundtrack here.

I dart to my left. As soon as I am out of its flight path, my terror turns to exhilaration. This is going to be a close encounter of the best kind!

It maintains course, soaring only inches from me. Our eyes connect as it passes. Its stare is not dead or full of ravenous bloodlust. If anything, it’s indifferent to me. It owns these waters with a quiet confidence. I’m a tourist here, and again, like a New Yorker, it couldn’t care less that I’m thrilled to be here.

Little do I know, I’m only at the start of a shark-filled week. And, if Belize has anything to say about it, a shark-filled future.

“Globally Significant Spot”

Three days before I find myself with a reef shark barreling toward my back, I board Belize Aggressor IV in Fort George Marina with my fingers tightly crossed for at least a brush with sharks on my liveaboard trip through the world’s second-largest barrier reef.

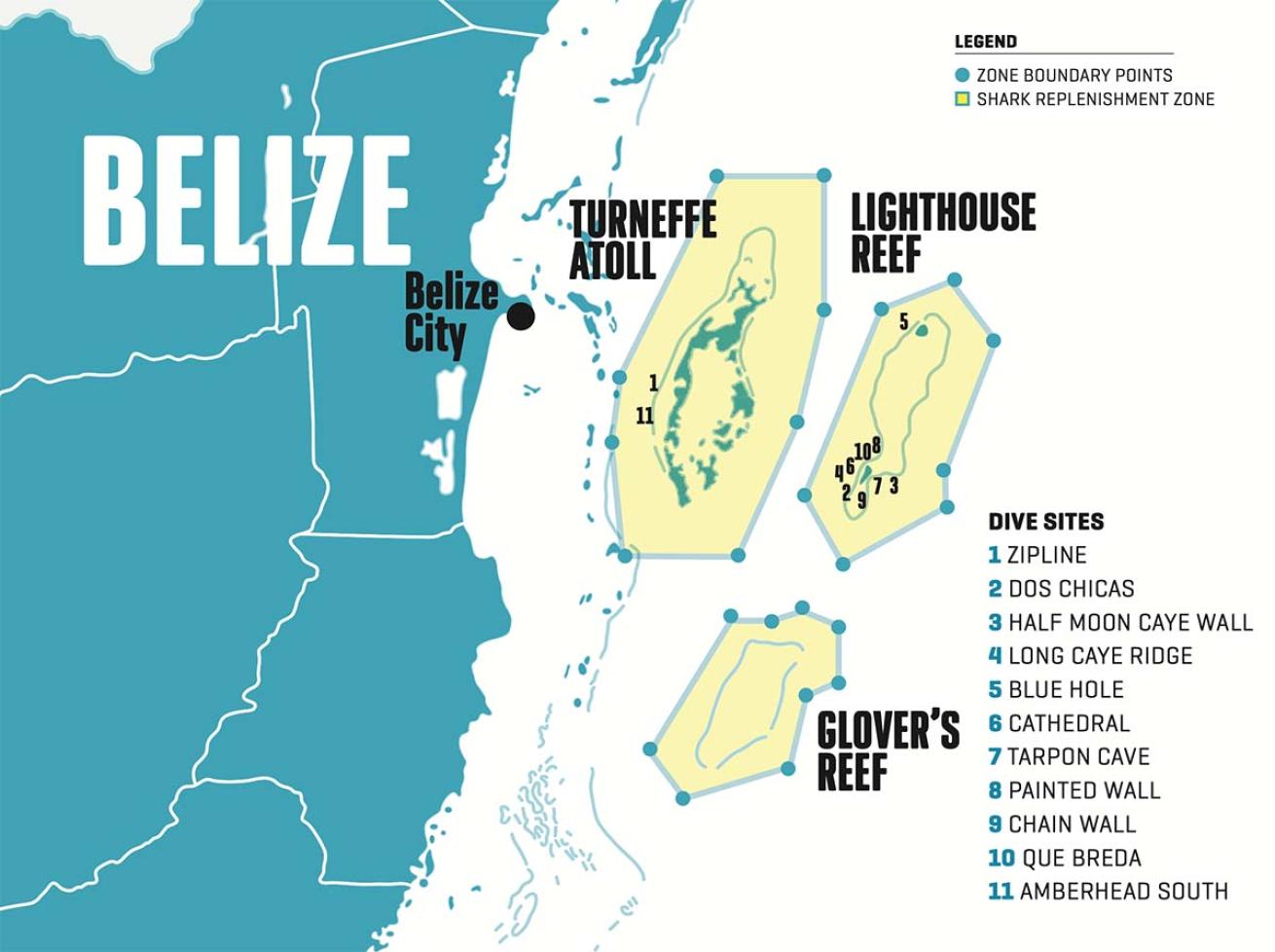

My itinerary involves 24 dives in six days across Turneffe Atoll and Lighthouse Reef, two of Belize’s three coral atolls. These reefs, along with Glover’s Reef in Belize’s southern waters, make up three of the four coral atolls found in the Western Hemisphere. In late June, about two months before my trip, the Belize Fisheries Department announced its intention to ban all shark fishing within 2 miles of the three atolls. Belizean Minister of the Blue Economy and Civil Aviation Abner Perez signed the regulations into law a month after I flew home, placing my entire trip within the roughly 1,500 square miles of a newly minted shark sanctuary with worldwide implications.

Map: Shutterstockcom/Frees; Illustration: Monica MedinaShark fishing is banned within 2 miles of Turneffe, Lighthouse Reef and Glover’s Reef atolls—three of the four coral atolls in the Western Hemisphere—creating about 1,500 square miles of shark sanctuary. The sites listed above, on Turneffe and Lighthouse Reef, were dived by the author on Belize Aggressor IV in this important area for global shark conservation.

The three atolls are a “globally significant spot,” says Dr. Demian Chapman, director of the Sharks and Rays Conservation Program at Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium in Sarasota, Florida. Chapman has studied sharks and rays in Belize for 21 years and was lead scientist of the 2020 Global FinPrint study, the world’s largest shark survey, which found sharks are functionally extinct on 20 percent of surveyed reefs.

According to the September update of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, nearly 40 percent of sharks and rays (the shark’s evolutionary cousin) are threatened—including the Caribbean reef shark. All of these threatened species are being overfished, says the IUCN, and a third face habitat loss and degradation. Scientists see a healthy shark population as key to thriving oceans.

“Sheer removal of sharks is linked to ecosystems degrading,” says Dr. Rachel Graham, founder of the tropical ocean conservation nonprofit MarAlliance, who has studied sharks in Belize for 23 years. It’s like eliminating wolves from a forest—removing this top predator leads to a spike in deer populations, putting pressure on forest regeneration as the deer turn to eating seedlings. Scientists believe removing sharks has the same deleterious effect on reefs.

“Lighthouse Reef is very important to Caribbean reef sharks throughout all their life cycle,” says Graham. Data gathered by Graham and her team over five years from 77 tagged sharks, published in August, found that, while teenage reef sharks moved to some other reefs, “those big mamas tended to come back to the [Lighthouse] atoll” to stay close to food sources—like reef fish spawning aggregations—and to give birth.

Of the sites surveyed in the FinPrint study, Lighthouse had one of the largest Caribbean reef shark populations in the world. And, “if you look at shark abundance nationally, it increases quite a bit out at these atolls,” Chapman says. This data informed Belize’s decision to institute the 2-mile no-fishing boundary.

This new shark-fishing ban is part of an ongoing effort from a Central American nation smaller in area than the state of New Hampshire to sustainably manage its oceanic industries. Marine protected areas around Glover’s Reef and Turneffe Atoll previously blocked the use of nets. The country outlawed trawling in 2010, placed a moratorium on offshore oil drilling in 2018, banned gill nets in 2020, and launched its Ministry of Blue Economy later that November. This year’s ban on shark fishing within 2 miles of the atolls is part of a larger law that also includes gear limits and size requirements for other marine life.

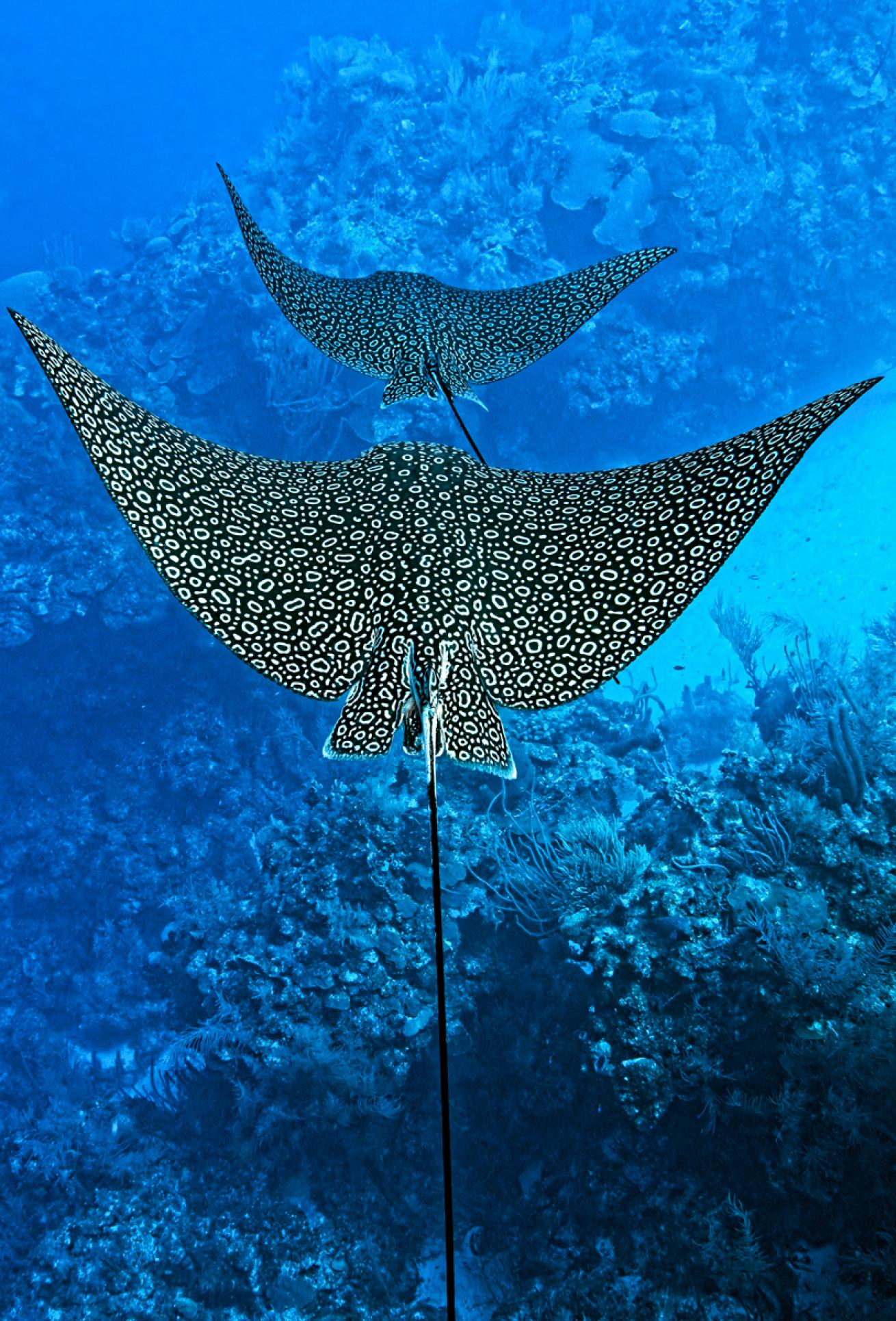

Scott JohnsonEagle rays soar past the Lighthouse Wall dive site.

Belizeans are reliant on keeping their waters vibrant. More than 15,000 residents are directly dependent on fishing daily, says Janelle Chanona, vice president of Oceana Belize. And tourism, driven in large part by the country’s oceanic allure, is a major contributor to the country’s overall GDP, one that was growing pre-pandemic.

Its management choices also have global policy implications, Chapman tells me over the phone before the trip. He sees Belize as a microcosm of the challenges facing nations dedicated to marine conservation that are also economically reliant on shark fishing.

On one hand, there are nations with significant shark tourism and a cultural aversion to eating shark—like the Bahamas, the Maldives and Palau—that “have banned shark fishing entirely because it’s easy,” he says. “Protecting sharks enhances lots of people’s livelihoods because the shark tourism is so important.”

On the other hand are developed nations that permit shark fishing and have the resources to run abundant stock assessments that protect against overfishing, like the United States and Australia. Then there’s everywhere else: too economically reliant on shark fishing to ban it entirely, keen to manage the fishery properly, and lacking the resources to consistently monitor shark populations.

Every “coastal country in the middle of that is going to have to do what Belize is trying to do,” says Chapman. “That’s why it’s a really interesting spot.

“Frisky”

To my delight, I’ve come on a particularly active week—not a day goes by without encountering a shark. On Sunday, our first day of diving, we meet Sampson, an oversize nurse shark fond of eating the invasive lionfish speared by engineer and divemaster Simon Villanueva. Later in the week I swim back and forth on a wall with Patches, a Caribbean reef shark distinguished by two white splotches bisected by its top fin. Even the Great Blue Hole, often thought of as lifeless, delivers. Brooke and John Howe, a couple in their 30s on vacation from Huntsville, Alabama, spot a hammerhead soaring in the smoky distance. It’s the first hammerhead sighting at the Great Blue Hole in three or four years for Villanueva, who dives there weekly.

“I never thought I’d dive with so many sharks I’d be like, ‘eh,’” says John on Wednesday, lounging in the shade of a second-deck couch between the day’s third and fourth dive. “I had it in my head: ‘You want to dive with sharks? Gotta pay a little extra.’ Not here. Is it Wednesday? Sharks. Thursday? Sharks.”

“There didn’t used to be so many, before COVID,” Aggressor’s second captain Shea Markwell tells me at the end of the week. “After COVID, there are so many sharks, especially at Long Caye.”

Scott JohnsonA giant barrel sponge at the Chain Wall dive site on the southeastern tip of Lighthouse Reef Atoll.

The pandemic squeezed the shark market, says Hector Martinez, a lobster fisherman who moved from fishing sharks to tagging them for Mote several years ago. Most of the sharks caught in Belize are exported, so movement complications dropped demand and price. “There has pretty much been zero shark fishing for the last few years,” he says. “There’s definitely a lot more sharks out there, because we see them when we’re diving for lobsters.”

Our encounters intensify as the week progresses. The sharks at dive site Tarpon Cave are “more frisky” than the ones at Long Caye Ridge, first mate and divemaster John Garraway tells us on Wednesday. “They’ll come in your face and then turn away.”

The moment we drop, two sharks are circling beneath the boat, cutting wide arcs through the grass before they follow us to the wall. As promised, I am face to face with them more than once. “They’re beginning to feel like a part of our dive group, but not enough that the excitement fades,” I write in my trip journal later that day.

Alexandra GillespieCaribbean reef sharks swim through a group of divers visiting Belize aboard Belize Aggressor IV.

Nowhere are these thriving sharks more apparent during this liveaboard trip than 42 miles from the mainland at Chain Wall in Lighthouse Reef.

“If you don’t want to be near them, just hang out at the edge of the group,” Markwell says during our Thursday-morning dive briefing. This strikes me as odd advice. After all, aren’t the fish at the edge of a school more likely to be the target?

I come to find his advice is spot on. Three reef sharks hone in the instant our splashes begin. They dart and meander and cut their way through the middle of the group over and over—often simultaneously. My head is on turbo, swinging from side to side for minutes on end. Occasionally all three of them are visible from a distance, but the majority of the time I have to pick one to focus on.

Beyond Paper Parks

Enforcement plans, key to making these protected areas more than a map, are still forthcoming.

“We will openly admit that enforcement is our biggest challenge,” says Beverly Wade, an advisor for Belize’s Ministry of the Blue Economy and director of the Fisheries Department. Co-managers, or the nonprofits that help care for and oversee protected sites, will play a critical role. Amanda Acosta, of the Belize Audubon Society, which works in Lighthouse Reef Atoll, co-managing the Blue Hole and Half Moon Caye natural monuments within it, and Valdemar Andrade, executive director of the Turneffe Atoll Sustainability Association, co-manager of Turneffe Atoll, are still developing their enforcement plans.

“Patrols and enforcement outside of the atoll for those few miles would have to be a joint venture between [the Belize Audubon Society] and Belize Coast Guard, as we don’t have the vessel size/type that is needed for enforcement at high seas,” Acosta tells me via email. “We do feel the best approach at this moment would be to deal with the fisherfolk through education and alternative sources of income [rather] than enforcement.”

“This whole thing has been parachuted in,” says Graham, who had previously worked with other local NGOs and shark fishers to advocate for a 4-nautical-mile sanctuary around the atolls. She says the fisheries department rejected the proposal a decade ago and local conservationists are now frustrated at “being sold back our own recommendations by others.”

Any fishing ban beyond 2 miles would be too restrictive for shark fishers to continue working, says Martinez. “You can’t do anything” in the space left from a longer ban. Both Martinez and Wade contest the notion the sanctuary announcement came out of nowhere, saying the 2-mile boundary was hashed out over several years in the National Shark Working Group, a multi-stakeholder task force of which Chapman, Graham, Acosta, Wade and Martinez are all members.

A Glimpse

Back at Chain Wall, I hang 15 feet below the boat from the safety stop bar. I’m more than 15 hours into the roughly 20 that I will spend submerged this week. Above me waits an open-air shower and freshly dried towel, but the reef shark posse hasn’t tired of us—nor I of them. I hold fast to the bar, watching one of our silent companions loop lazy circles above the sea grass meadow.

In the coming years, Chapman and locals like Martinez will drop baited underwater remote video stations into these very waters to gauge whether local shark populations change over time with the new fishing rules. This data will be given to the government in the continued hope of shaping a sustainable future for both the sharks and the dozens of fishers reliant on them.

The rushing current tries to yank me away from the bar, encouraging me to end the dive, to surface, to trade the land of the sharks for sun and sea legs. But I don’t give. Not yet. I can’t stare long enough at this sliver of a shark-filled future.

Alexandra Gillespie

FOLLOW ALONG

Mote Marine Laboratory’s Center for Shark Research and its partners have tagged several sharks in Belize to track their movements, including three silky sharks and two tiger sharks—Alan, Belekin, El Tigre, Mario and Stann. Follow their journey on the Global Shark Tracker.

NEED TO KNOW

Operator: Belize Aggressor IV departs on Saturday evenings from Fort George Marina, located in Belize City, and returns to port the next Friday at noon. This yacht is a 138-foot joyride with a 26-foot beam that hosts up to 20 guests in 10 rooms. Rooms offer a mix of twin, queen and king beds. The salon is air-conditioned, and the cocktail deck is shaded. Beer and wine are complimentary, and liquor is bring-your-own. Group scuba amenities include a photo-editing computer, fish ID books and camera tables. Diving is from the boat, but optional shore excursions can be taken on the 15-foot tender. All itineraries include Lighthouse Reef Atoll, Half Moon Caye and Turneffe Atoll.

Local Language: English

Courtesy Aggressor AdventuresBelize Aggressor IV

Getting There: Flights leave daily from Houston, Miami, Atlanta and Dallas to Philip Goldson International Airport in Belize City. Plan to arrive the day before the boat sets sail. Aggressor offers hotel bookings and airport transportation.

Dive Conditions: Water temps are warmest between August and October, around 82–84°F; the water is about 78°F from November to July. Visibility ranges from about 40 to more than 100 feet depending on site and conditions.

Trip Tip: You’ll be stuffed after dinner, but don’t skip the night dives. These reefs are bopping with squid, octopuses, eels, shrimp, crabs and more after sunset. Plus, post-dive, the crew serves up a delicious mix of hot cocoa and Jamaican rum cream.

Onboard Expertise: Second captain Shea Markwell is master of the macro; follow him to find minute nudis and bouncing jawfish.

COVID Travel Requirements: At the time of publication, a negative COVID test is required both to enter Belize and return to the United States. Belize requires a negative PCR test within 96 hours of the trip or a rapid antigen test within 48 hours, presented before boarding your flight. Aggressor arranges for a medical team to board the boat upon return to port to test guests for their U.S. re-entry.

Price Tag: A seven-night cruise on Belize Aggressor IV ranges from $3,195 for a deluxe suite to $3,395 for a master; a $130 port fee per guest is charged at the end of the trip. Unlimited nitrox is $100.