Into the Frenzy: Diving Baja's Mobula Ray Aggregations

On March 6, 1940, the chartered shrimp vessel Western Flyer pulled away from the dock in Monterey, California, with author John Steinbeck and crew, including marine biologist Ed Ricketts—waving from the deck. Their six-week journey to the Sea of Cortez would cover roughly 4,000 miles. Western Flyer was stuffed to the brim with glass vials, specimen jars, and hearty provisions to sustain the crew on their long, arduous days searching for marine invertebrates. Those they found would be killed, preserved and cataloged in the name of science.

Brandon ColeView of UNESCO World Natural Heritage Site Espiritu Santo Island from above.

Map of BajaThe six-week, 4,000-mile journey undertaken in 1940 by author John Steinbeck, marine biologist Ed Ricketts and their hardy crew began in Monterey, California, meandered down to Cabo San Lucas and curled around the Sea of Cortez before returning north.

Eighty-two years later in Baja California Sur, Mexico, I clambered aboard the soggy deck of Kochimini, our 28-foot fiberglass panga, and headed for those same productive waters. I live on the central coast of California, where Steinbeck’s legacy is impossible to ignore. I sat only half a mile from his preserved 900-square-foot cottage while I dug hungrily into Sea of Cortez, the travelogue that resulted from his mission all those years ago, and reflected on the parallels—and deviations—in our voyages.

Western Flyer reeked of the formaldehyde and rubbing alcohol used for specimen preservation; our Kochimini was saturated in a more pleasant aroma of sea breeze and soggy neoprene. The deck of Western Flyer teemed with nautical charts—ours was loaded with drones and heavy videography equipment. On their journey, Steinbeck and Ricketts pondered the interconnectedness of our world: “The true biologist deals with life, with teeming boisterous life, and learns something from it, learns that the first rule of life is living,” Steinbeck wrote. And learn he did. His days in the Sea of Cortez, also called the Gulf of California, were spent searching under rocks—”ferocious with life”—for tiny wonders that taught him about the ocean as it existed then.

As for me, I was tagging along on a photo expedition with professional photographer Brandon Cole; his wife, Melissa; and our guide, marine biologist and filmmaker Erick Higuera. Rounding out our crew was Siddharta “Sid” Velazquez—a spotter-plane pilot hired to be our eyes in the sky and better our chances of finding our targets: giant aggregations of pancake-like mobula rays that show up each year, and if happenstance allowed, the orcas that feed on them. Our focus was pure observation, but we were driven by the same interest in life, the same desire to study it. No samples were collected, no rocks overturned, and no animals harmed.

Related Reading: The Best Dives in Mexico's Baja California Sur

Our starting point, La Paz, lies at the tail end of the long, dry Baja California Peninsula, where the Gulf of California to the east bleeds into the Pacific Ocean to the west. As we motor out on our first day, the water flashes silver and sapphire. The wind tangling my hair will drive the mobulas to deeper water, Erick tells me, but when the wind dies down by late morning and it’s flat, they start to jump. I check my watch—9:13 a.m. As a wildlife videographer, Erick has spent countless days in and around the animals that reside in these depths, so we follow his nose, relocating frequently to scope out new patches of water, and moving along when the action fails to appear. Frigate birds circle our sleepy panga. Their prehistoric, broken looking wings slice the crisp blue sky that has started to peek through the mist.

Illustration by Andrea DingledeinThe Adventures of Steinbeck and Ricketts

Flying Tortillas

Once outside of La Paz, the Gulf of California feels deserted and ancient. Barren cliffs the color of sunbleached bricks slope gently into the sea, their folds and deep grooves surrounded by a brilliant navy hue—a color Steinbeck referred to as “tuna water.” These productive waters churn with megafauna: whale sharks, hammerheads, orcas, sea lions, dolphins, blue, sperm and humpback whales, turtles and mobula rays, to name only a few. Mobula rays (Mobula munkiana)—also called Munk’s devil rays—are the manta’s smaller, shyer cousins. They congregate here en masse to mate and give birth. In addition to their impressive ability to gather in the hundreds of thousands, they are also phenomenal jumpers. They can reach vertical heights of nearly 10 feet. When they splash back into the water, the sound cracks the surface like lightning, earning them the nickname “tortillas” from local fishermen. When I asked Jay Clue, owner of local dive shop Dive Ninja, why, he responded with a tortilla-making video tutorial. “Close your eyes and picture mobulas,” he texted. I closed my eyes and listened to the woman on screen vigorously pat the uncooked masa with her hands—slap, slap, slap. “I totally get it now,” I answered. It’s unclear why they jump—it could be to dislodge parasites, to communicate with other rays, or to impress a mate, but whatever the reason, it is a transfixing sight.

Brandon ColeMobula rays leap from the water, reaching heights of up to 10 feet. This may be to communicate or dislodge parasites—or it might be a mating display—scientists aren’t entirely sure.

Or so I had heard. Two hours in on this first day, we still haven’t seen a single ray. Erick stands at the bow, his knees bending and flexing with each wave that lolls under the boat. The drone in his outstretched hand whirs to life and springs 20 feet into the air. From this new vantage point, we spot something that could be a big school of mobulas 30 yards away. We snap to attention like a pack of wolves on the hunt. Erick peers over the edge of the panga as we creep along, searching. The anticipation reaches a crescendo as the limits of my patience are tested. Pop!

A mobula flings itself into vertical flight at my 2 o’clock and my heart soars along with it. And then the silence is broken. The first brave ray having made its inaugural leap, the others now follow suit. Gleeful little leaps and energetic slaps echo around us, sometimes only feet from the boat. Some rays go for distance. Others fail to launch, clumsily tumbling back into water that is thick with wings. Several somersault and twist in the air before landing square on their cartilaginous backs. Most jump three times in a row.

Brandon ColeMobula rays (Mobula munkiana) grow to only 4 feet and swim together in the thousands. The productive Sea of Cortez provides ample food, and the rays gather there to eat, mate and give birth seasonally.

Erick points out the round little bodies of some pregnant rays as they, too, leap from the depths, seemingly unencumbered by their present condition. Erick has witnessed several airborne deliveries—live pups ejected from their mothers midleap, their first moments alive suspended in air, rather than water.

Brandon scrambles to aim his camera at the jumpers, swinging his lens left and right with each subsequent slap! Too late. Each ray makes contact with the water once more and sinks below, shot missed. “Come on, you crazed little bats,” I hear him mutter as another launches just outside the frame.

After some time, Brandon puts his camera down and sighs. The creases in his forehead unfold as he accepts defeat. “They look mustard-colored in the green water,” he says. The water’s jade tinge is precisely what draws these rays to the area, and probably has since before Steinbeck, or I, or anyone else was here to observe it. “Microscopically, the water is crowded with plankton,” Steinbeck wrote of the living tint. Under the boat, the rays chug swigs of emerald seawater and filter it through their gills, trapping the microscopic morsels.

When they splash back into the water, the sound cracks the surface like lightning, earning them the nickname “tortillas” from local fishermen.

Brandon ColeMarine biologist and filmmaker Erick Higuera deploys a drone to determine the size of a mobula aggregation;

We fall silent as the school starts to lift toward the surface, swooping past in never-ending waterfalls. I notice some rays have traces of a white fungus, while others have mating-ritual bite scars. A few have the telltale tooth marks that could only come from an orca.

“We’re placing ourselves right in the middle of the food chain,” Brandon tells me, noticing the same scars. Some pods of orcas prey exclusively on rays, he explains. Other pods prey on sharks, pinnipeds, cetaceans or fish, and others still are generalists, eating whatever they can find. Erick chimes in: “It’s like vegans and meat eaters and vegetarians; orcas have different diets.” We’re here to see mobula rays, but I must admit the idea of a chance encounter with orcas while they stalk their prey thrills me.

Fever Pitch

Brandon ColeAuthor Ariella Simke swims with the rays

We slide into our weight belts and pull on our fins in preparation for our first introduction to the school. “Don’t make any noise when you get in the water or it’ll spook them,” Brandon warns. I straddle the side of the panga and enter with a small splash. Fifteen feet below me, I can see my graceless entry hasn’t bothered the rays, as they continue to tightly circle.

Brandon, Melissa, and Erick drop in behind me and we move like a pod, signaling and staying glued together to avoid encircling the rays. This behavior, reminiscent of orca hunting behavior, would likely chase them deeper. “You have to gain their trust before you make any dives,” Erick says. We stay on the surface, gently acclimating the fever to our presence.

They begin to rise, accepting us into the fold, and Erick silently plunges down. They jostle, then fill in their own gaps slowly, like a thousand simultaneous zipper merges on the world’s most glorious highway. Erick hovers below them. And then something magical happens. They begin to encircle him until, oxygen depleted, he is forced to ascend.

Thousands of gray-yellow bodies circle clockwise in unison, creating a powerful gyre. “They’re vortexing!” Erick yells over the splashing.

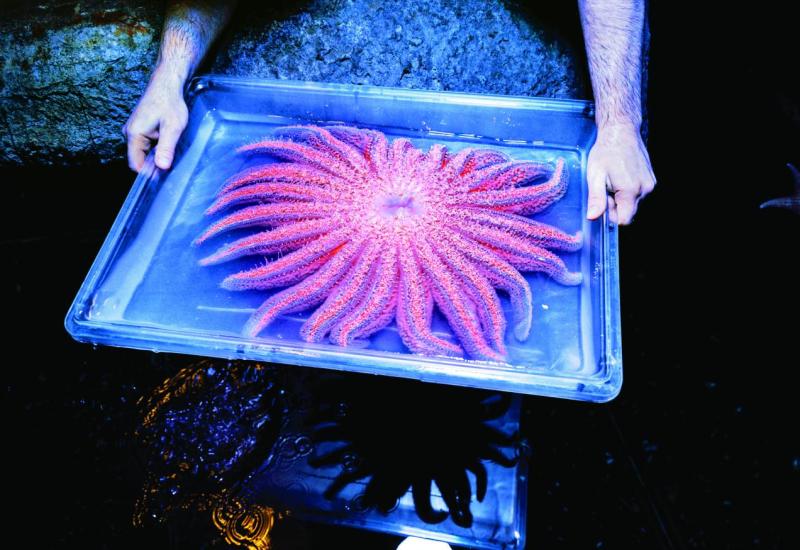

Brandon ColeA mobula ray exhibits wounds likely acquired from an orca bite.

The rays appear both chaotic and perfectly choreographed. They pack together, yet rarely touch. Their wings shimmer with the tattooed ripples of the reflected water above. Once in a while a solitary individual appears overcome by a wild itch and, twitching and spasming, tears away from the herd and bolts for the surface in a fit. We continue to freedive, careful to leave spaces in between dives to keep the rays copacetic.

By late afternoon the viz has deteriorated into what Erick calls “green beans.” Taking a cue from the rays, we launch ourselves out of the water, peel off our suits and get underway back to La Paz. Sleepy and salt-encrusted, I watch the landscape slide by.

Related Reading: Battling for the Future of Striped Marlin During Mexico's Secret Sardine Run

Brandon ColeMelissa Cole dives with a group of mobula rays

Each day follows like the first; the days blur together as they do when a routine is established. I wake up with legs stiffened to the point of paralysis from hours of kicking. Blisters have popped up on the back of each ankle where my fins chafe. My eyelids feel broiled, and yet, my excitement grows with each new morning.

Brandon ColePilot Siddharta Velazquez flies a spotter plane to gather scientific data and assist local scientists

One afternoon, while we are anchored in about 80 feet of blue water, tens of thousands of rays fill the distance between us and the sandy bottom. They move quickly, and we fight hard to keep up, sucking mouthfuls of air through our snorkels. Thousands of gray-yellow bodies circle clockwise in unison, creating a powerful gyre. “They’re vortexing!” Erick yells over the splashing. Vortex feeding lets the rays condense the plankton in the water and scoop it up efficiently. Floating above the center, I stretch my body to form a straight line from my fin tips to my outstretched fingers, holding tension in my muscles like a rigid plank. The whirlpool starts to turn my body like the hands on a clock. When I dive, their collective inertia pulls me deeper into the eye of the tornado.

Over the next couple of hours we swim with several schools, leaving as soon as we detect any avoidance on their part. On the surface, a curious sea lion pup swims up to Brandon for a brief play session. Then a flat, wide figure comes into view behind it. As the barnacle-clad sea turtle cruises by, Brandon and I raise our faces out of the water. “Turtle!” we exclaim in unison, breaking out in laughter. Before I can catch my breath, a sea angel flits by. I follow it with my eyes. When I turn back to the mobulas, they are gone.

Closing The Gap

Brandon Colea bright mural in La Paz

It’s hard to know how the animal life we’re experiencing today compares to what Steinbeck saw. In his journals he wrote: “The abundance of life here gives one an exuberance, a feeling of fullness and richness. The playing porpoises, the turtles, the great schools of fish which ruffle the water surface like a quick breeze … The sea here swarms with life.” This sea has weathered enormous changes since Western Flyer passed through. Overfishing cleared the water of highly vulnerable species like oceanic manta rays and hammerhead sharks that were once prevalent.

At the urging of conservationists, management plans were implemented. Bit by bit, the ecosystem has been rebuilding to its former glory. But a lack of historical data provides only a small window into the past, altering our perception of what is normal—a phenomenon called “shifting baselines.”

Brandon ColeA pod of orcas swims serenely in Baja

While past management plans in Baja have encouraged a conservation mindset around certain species, such as whale sharks, local marine scientists like Erick and his wife, Francesca Pancaldi, must now contend with a new kind of unregulated animal encounter splashed across social media: swimming with orcas.

Brandon Cole“In Search of Killers,” a painting by Melissa Cole, inspired by the magic of the Sea of Cortez and our photo expedition

Orcas enjoyed a somewhat covert existence in Baja until about two years ago, when people began posting videos of their chance encounters online and interest soared. In a call after my trip, Erick and Francesca tell me that no one was prepared for the resulting influx of visitors. “The way that tourism is growing has no order at all,” Francesca says. There are currently no specific regulations to manage the activity, and local conservationists are worried. Jay tells me that without regulations, orcas are often chased and harassed. What we know about orca behavior is very limited, but researchers have studied the effects of boats on their movement patterns. “The noise produced by the number of boats surrounding orcas changes their behavior for the worse,” Erick says. “They swim faster to get away, they dive deeper and longer, and they come back to the surface even a mile away from the boat.”

But tourism demand entices some operators— a number of which operate without proper permits—to force interaction even when it is harmful to the animals. “It’s not only dangerous for the animal, it’s also dangerous for people,” Francesca says. If an accident were to happen, it would be bad news for everyone involved. The social structure of the species is also very complex, and we may be interfering in detrimental ways that we don’t yet understand.

“We are trying to collect scientific data to help the government create a proper management plan for interaction with orcas,” Francesca says. Such a plan would dictate best practices for interacting with orcas, based on available science and input from various stakeholders. It would determine the number of boats permitted in an area with orcas present, when and how people can interact with them, and when they must be left alone—during sensitive activities, like feeding, mating and nurturing young.

While some locals work toward a management plan, others believe banning the activity outright is the best way forward. Current regulations governing interaction with whales, such as sperm whales and humpbacks, are often ignored without repercussions, leading to skepticism that an orca management plan would be any better.

Brandon ColeFrancesca Pancaldi analyzes cetacean tissue samples in the lab.

The Way Forward

As I learn more about the issue at hand, I feel a deep discomfort. My conversations with Erick, Francesca and Jay make me think back to my own initial reactions seeing those captivating orca videos online. Astounded by their beauty and grace, I felt the itch to swim with them too. Am I a part of the problem? But they all stress that wildlife tourism in and of itself is not the issue. In fact, conservation minded tour operations like Dive Ninja are supporting ongoing research in a big way.

Government funding for important conservation projects is hard to come by, so researchers partner with tour operators to share resources, conducting fieldwork from their boats while simultaneously educating visitors and thus bridging the funding gap by creating a meaningful and educational tourist experience.

I asked Jay if there was any way to see orcas responsibly. The only way is by chance. Until the activity is better regulated, Dive Ninja doesn’t specifically offer orca tours, but it does run mobula ray citizen- science expeditions. “Come for the mobulas, something that you’re guaranteed to see, and if you’re lucky, you’ll also see orcas hunting them,” he says.

Brandon ColeA scene from the La Paz beach where Kochimini departed each morning

Not Meant To Be

Our last day on the boat came and went. I never did see orcas, but I couldn’t be too disappointed. After speaking with the scientists, my perspective has shifted. This encounter is not something to check off a bucket list. It cannot be chased—you have to take what the ocean delivers. Sometimes the orcas show up of their own accord and other times, they don’t. Their autonomy is what makes the encounter worth having at all.

Interaction is an inevitable and beautiful part of life. Interaction between people and the sea, mobulas and orcas, even science and tourism. As divers, we spend much of our lives in the water, and as Steinbeck says at the finale of his journey: “We search for something that will seem like the truth to us; we search for understanding; we search for that principle which keys us deeply into the pattern of all life; we search for the relation of things, one to another …” Through the eyes of the local scientists, I saw the interconnected nature of this ecosystem and our place as humans within it. In 1940, Steinbeck studied the sea unencumbered by social media, before drones and spotter planes were in a scientist’s arsenal and wildlife tourism drew hordes of people to the area each year. And yet our stories are not so different. This vibrant sea still has the same effect on people now as it did then. Through all its iterations, struggles and triumphs, the Sea of Cortez is a living testament to the power of interaction and the evolving interdependence we are all a part of.

NEED TO KNOW

Water temp: 72 degrees

Exposure suit: 5 mm freediving wetsuit

For more information on cetacean and ray research in Baja, check out the work of the Rufford Foundation and the Mobula Conservation Project.