A Look Back At the Scuba Diving Pioneers of the National Park Service

Courtesy National Park ServiceAll In A Day's Work

Sgt. Ted Chittick of the U.S. Park Police after a dive in the Tidal Basin in Washington D.C., in 1965.

The National Park Service, which is celebrated it's 100th anniversary this August, was the first civilian federal agency to adopt scuba diving as an important management tool. Its dual mission — “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects” and “to provide for the enjoyment of the same,” as established by Congress in August 1916 — compels the NPS to manage parks in their entirety, including underwater.

At the end of World War II, soldiers and sailors returning from the South Pacific brought back a smattering of dive training and equipment, courtesy of Uncle Sam. Books, movies and war-oriented comics inspired mostly young park visitors to explore underwater, if only by holding their breath. A few resolute rangers quickly followed. Now a new book slated for release this fall — National Park Service Divers — Protecting Nature, Preserving the Past, Recovering the Dead by Charles R. “Butch” Farabee and Daniel J. Lenihan — tells that story.

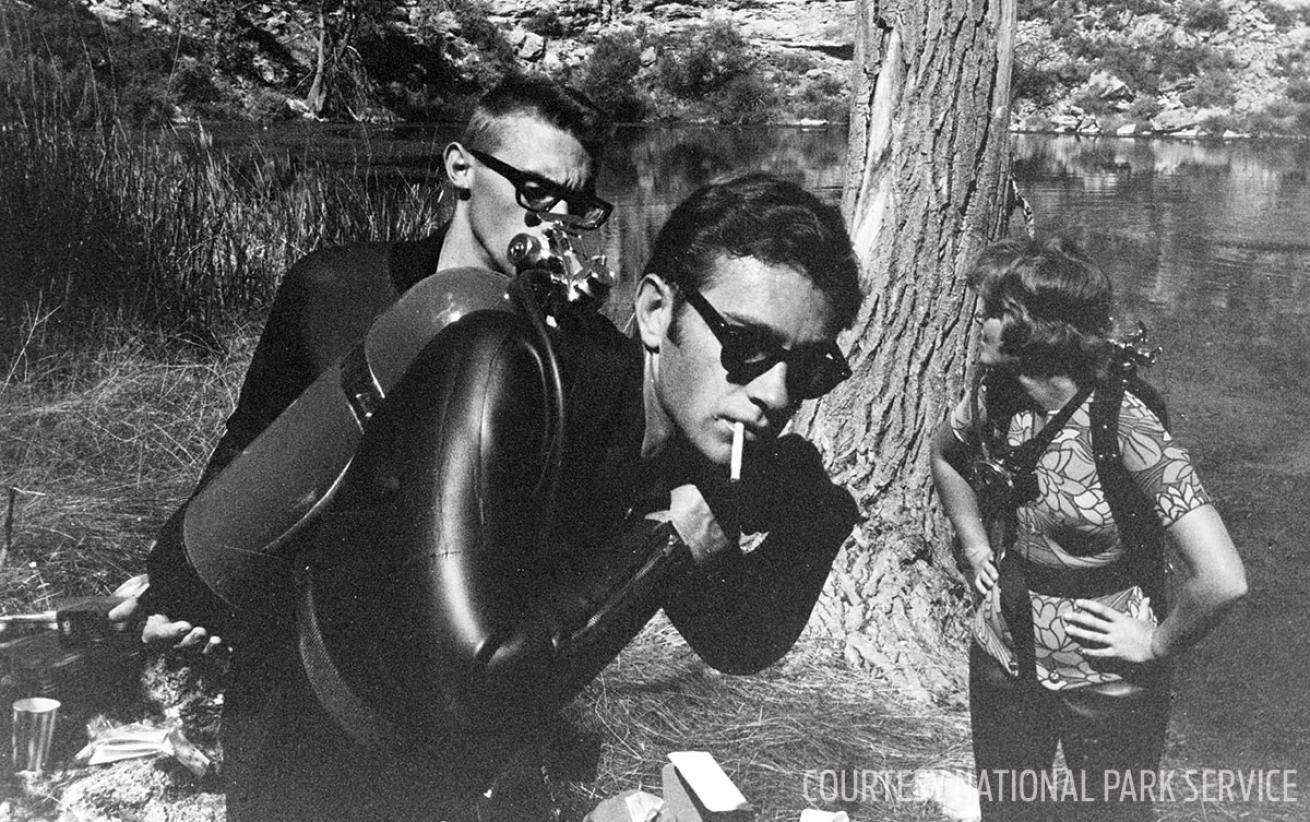

Courtesy National Park ServiceThe Early Days

Some of NPS' first diving archeologists at Montezuma Well in Arizona in 1968.

Through the 1950s, a handful of NPS areas, such as Channel Islands, Olympic, Isle Royale and Death Valley (Devils Hole) national parks, began seeing scuba diving by the general public. Many of the places in the park system that initially received the most attention from divers were inland in the desert Southwest, such as Lake Mead, Amistad and Glen Canyon national recreation areas.

In the mid- to late ’50s, a few intrepid NPS personnel also began diving. Although these rangers lacked formal certification and training, the service has identified isolated instances of employees being “on the job” underwater as early as 1957.

Recognizing the need for standards and guidance, an NPS diving policy for internal use was first issued in 1963. For decades, scuba has been part of park service protection, research, maintenance, interpretation, and cultural and natural resource management. Since the mid-1960s, dive tanks have been added to guns, ropes and fire packs in ranger caches.

Courtesy National Park ServicePractice Makes Perfect

Drills like this circa-1966 car sinking at Texas's Amistad National Recreation Area prepared rangers for emergencies.

Over the years, rangers have dived white shark breeding grounds, surveyed WWII ships sunk in nuclear blasts, explored deep submerged caves, felt among the detritus of New York Harbor for weapons used in crimes, and recovered body parts of drug pushers along the Rio Grande. Others have tracked lobster migrations, excavated the HL Hunley, a Civil War submarine, and accompanied French divers on 200-foot dives to the remains of the CSS Alabama, a Confederate raider sunk in the English Channel.

NPS divers regularly check accumulation of oil leaking from the USS Arizona in Pearl Harbor. They have participated in saturation diving, mixed-gas diving, cave diving and rebreather diving, and searching submerged planes, helicopters and automobiles for accident victims. They’ve used submersibles, jumped from helicopters in full scuba, entered deep shipwrecks, and used oxy-arc torches to cut away boating obstacles.

As the National Park Service celebrates its centennial this month, today’s National Park Service divers are well-trained, highly motivated and work in the shadow of a great tradition.

- Want to dive some of these underwater gems yourself? We've created a list of our favorite scuba friendly National Parks.