What It's Like To Scuba Dive After Jumping Out of a Helicopter

Steven P. HughesDivers jumping from the helicopter wear full scuba gear, except for their masks and fins.

The helicopter door opens right above the ocean and wind floods in. That’s when the diver’s perception narrows: He stops hearing the thumping of the rotor blades. He sees only my hands — nothing else. That’s the adrenaline rush. If he panics, there will be problems. If he doesn’t jump, the dive is scrubbed because his buddy can’t climb over him to exit.

But let me back up. I teach heli-diving for OC Helicopters in Los Angeles and I’m the only PADI Heli-Diver 1 specialty course instructor in the world. We’ve been offering this course since 2014, and The Department of Homeland Security only allows U.S. Citizens to participate.

So let’s start from the beginning. There are two types of jumps: a non-certifying jump and a certifying jump (the specialty requires two jumps). Typically, divers have time for just one jump a day.

When you climb aboard the helicopter, keep your hands low, no higher than your head, or that will be the last time you put your hands up.

Then you’re inside wearing all your dive gear, save for your fins and mask. Those are strapped to your chest. Your air is on. In the event that you have a problem, we want to make sure you can breathe.

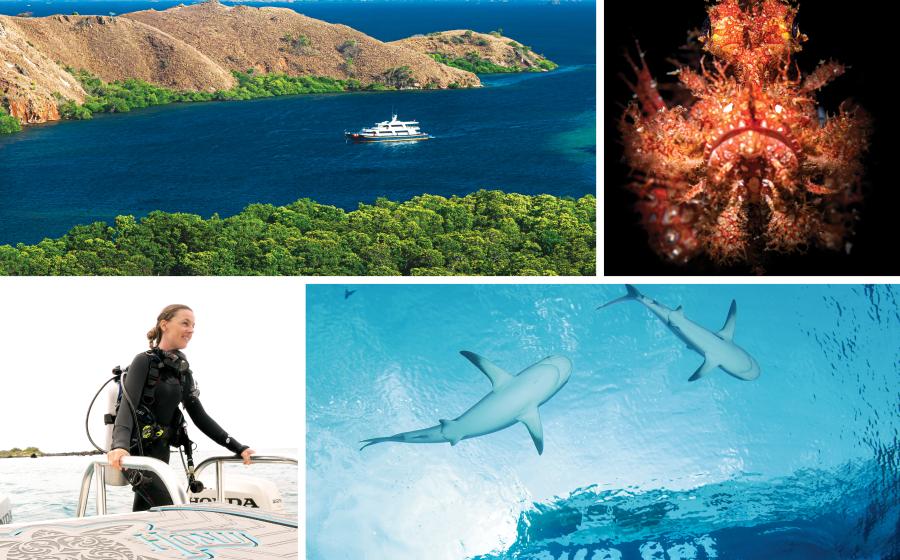

We drop jumpers at one of three locations, where, after the drop, the dive proceeds as usual, aided by a divemaster who joins via a chase boat. Fly time to Catalina Island is between 15 and 18 minutes. To the Eureka oil platform, about 8 minutes, and to Deadman’s Reef at Laguna Beach, about 6 to 8.

That’s a lot of time to think about what’s about to happen as you’re strapped in.

As we approach, I slide the door open. Several jumpers have told me this is when it gets real.

And while this is happening, I’m communicating with pilot Ric Webb. He has to anticipate the changing weight displacement occurring when roughly 200 pounds exits one side. If he doesn’t, the helicopter would pitch too far in one direction suddenly.

When it’s time, if you’re diver one, you unbuckle first. I have a hold of you. You scoot left, stepping onto the step. Below is the ocean, 15 feet down. Nobody ever asks for a higher jump.

Then you have to step. Not jump. If you jump, you push down, placing too much weight on one side of the helicopter.

As you’re in the air, you look slightly down. If you don’t, you’ll faceplant.

That free-fall is why we do this. I’m always looking for that rush in diving, and for me, this is it. If you have to ask why someone would want to do this, then heli-diving isn’t for you.

MORE CRAZY — BUT TRUE — DIVE STORIES