Finding Hope for Florida’s Bleached Corals

Jennifer AdlerA healthy coral releases gametes into the water column.

At sunset, we splash into the 86-degree water, dodging moon jellies as we swim toward the hauntingly white corals. It’s early September, two months after a severe bleaching event on Florida’s coral reefs, and we’re here, 5 miles offshore at Looe Key, to see if any of the bleached corals will spawn. I’m a photojournalist here with Vox reporter Benji Jones to document the bleaching and the scientists studying it.

Corals spawn at night, usually one week out of the year in the evenings following a summer full moon. This year is a split-spawn year, basically a leap year for corals, when mass spawning occurs over two consecutive months. Bleached corals are stressed and therefore less likely to spawn, so the bleaching event combined with the tricky split-spawn year means we may not see spawning at all.

This is Dr. Hanna Koch’s sixth spawning season. She and Celia Leto, both coral reproduction scientists at Mote Marine Laboratory, create and raise coral offspring to restore reefs in Florida. According to Koch, if we see spawning despite the devastating bleaching, it would be miraculous.

Koch and Leto lead our sunset dive. We swim through dead and bleached corals, some centuries old, and Koch marks six healthier corals she thinks are most likely to spawn with glow sticks that become neon green beacons when cracked. I try to remember the pattern of lights for later—these are the corals we will monitor in the dark.

Related Reading: The Warriors Fighting to Save Florida's Dying Corals

Back on the boat at 8 p.m., we switch tanks, eat dinner and prep for a late night of diving. Adrenaline levels are high. Jones is interviewing Koch when Leto and I let out muffled screams of excitement. Blue bioluminescence dances at the edge of the boat. We swirl our hands in the warm water, and it lights up an electric blue.

At 9:30, we splash again, learning the pattern of green lights as we swim between coral colonies to monitor for spawning. We use red light to look closely at the coral polyps—direct white light can interfere with the cues colonies are looking for from the moon, but once the gametes are released, we’re able to use our normal dive lights. Looking up to the surface, we find we’re not alone: Dozens of barracuda reflect the light like long, slender disco balls. But we stay focused on the corals and the bioluminescent blue halos around us as we swim.

After an hour, we come up to quickly switch tanks for a third dive. It’s past my bedtime, but that’s not even remotely on my mind as I jump back in, dodging moon jellies on the surface, and head for the green markers hovering at each of the six marked corals. The pattern is much more familiar after a few hours in the water.

Each time we swim by a coral, we’re looking closely at its polyps to see if they’re “setting.” The little pink gamete bundles (eggs and sperm) sit in the mouth of the polyp before they’re released—a trained eye can spot this sign that the coral is about to spawn.

Related Reading: Unprecedented Mass-Bleaching and Significant Coral Mortality in the Florida Keys

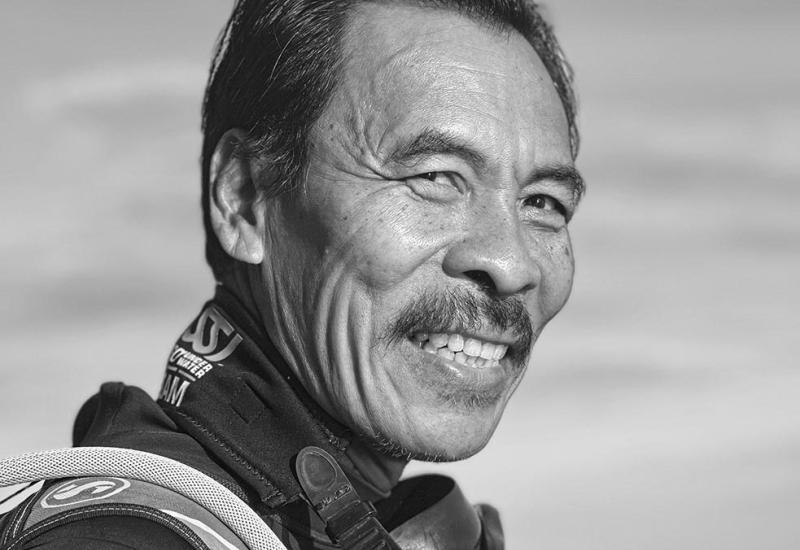

Jennifer AdlerAt sunset, Koch swims through patches of bleached and healthy coral to mark the likely spawners with glow sticks.

Suddenly, our red blanket of light is disturbed by Koch’s dive light flashing around as if she’s at a concert. I’m not sure whether to be worried or excited, but when I turn to Leto, her eyes are huge behind her mask—it’s her first time seeing spawning in the wild too, and she’s freaking out. The minute-long swim to Koch is a blur.

Sure enough, Koch has spotted setting—the polyps are more open, and there is a tiny gamete bundle ready to pop out of each one. I switch my video lights from red to white to capture the moment, and worms flock like moths to a flame. I’m glad to have a hood on so nothing swims into my ears.

For the next 15 minutes, we hover in the pitch dark, staring at this one healthy lobed star coral. Gently and without fanfare, the tiny pink bundles start to release, hovering at first near the coral and then floating up into the water column like tiny balloons.

Related Reading: The Coral Classroom: A Lesson in Restoring Reefs and Mobilizing Action

Although these bundles contain eggs and sperm, they need to find gametes from other colonies to fertilize. They are viable for only a few hours, so the race is on. We only see one coral spawn, but there are surely others out there. We wish the bundles luck as they drift off into the darkness.

Heat tolerance is genetic—this particular coral avoided bleaching during a historic marine heat wave and is now passing on its heat tolerant genes to a new generation of corals.

While it felt a bit random to be floating out in the middle of the ocean and see a coral spawn, there’s a science to it. “Our predictions work,” Koch tells us after the dive. “This was one of the peak predicted nights.” Hopefully, the other corals were in on it too—they need all the help they can get.

We high-five underwater and collect the green glow sticks from the reef. It’s midnight when we surface. “I’m so jazzed, I’m not going to be able to sleep tonight,” Leto says. It’s 3 a.m. when I make it back to my hotel room, and I’m in the same boat. There’s no amount of caffeine that can keep me awake until this time of night, but coral spawning did the trick.