American Waters: Q&A

Alex Kirkbride

The underwater photographer and author of American Waters shares the inspiration for his three-year, 108,000-mile odyssey to document this nation's myriad waterways.

Q: How did you get your start in photography?

Q: You live in Hove, England, yet you chose to focus your project on American waters. Why?

Alex Kirkbride: I am actually a native New Yorker. I spent the first six years of my life in the U.S., and then we moved to England, where I lived until I was 22. So I grew up with an American mother in London, with both American and English cultures, and have always felt torn between both countries. From 25 to 42, I lived in New York City and felt it was time to move back to the UK. But I wanted to say something about America before I returned, something that hadn't been said before photographically--something substantial enough for me to feel OK about leaving the States.

AK: I began to learn underwater photography in 1982 by taking pictures at night when I wasn't in charge of a night dive as a divemaster at the Riding Rock Inn, San Salvador, Bahamas. Then, part of my job at the Rum Cay Club, Rum Cay, Bahamas, was to take photographs of the guests underwater. At the same time I took a correspondence course from a photography school in New York. The course taught me the fundamentals and the rest I picked up by trial and error. After a while I had accumulated enough images to make a slide show. A few professional photographers came down and remarked on my work. Initially, I just thought they were all being polite! However, one pro came back the next year and remarked on my improvement. At this point I realized that I could have the ability to pursue photography as a career. So instead of going to photography school, I became an assistant for five years in New York City before I started my own business.

Q: What about diving compels you as a form of exploration and discovery?

AK: To see places few people have had the chance to see and the opportunity through photography to show people what is down there. I feel very fortunate to be able to do this.

Q: You took 848 days to complete this project, covered more than 100,000 miles, went on 945 dives and spent some 732 hours underwater. How did you keep motivated?

AK: I had wanted to make a book since I was 12 years old, so it wasn't too hard to keep motivated. I felt this was my opportunity and I wasn't going to let it pass, especially after having been forced to delay the project for two years due to illness. However, there were times when it was tough to keep motivated. But then I would meet someone who was genuinely enthusiastic and excited about what I was trying to accomplish. This enthusiasm, which I was surprised happened time and time again, encouraged and inspired me.

Apart from that, sheer determination and willpower, perseverance, fear of failure and running on adrenaline.

I'm glad to say I was able to rise to the challenge, as I honestly didn't know at the beginning if I was going to be able to keep up. There were days when I felt I couldn't get in the water from exhaustion, and Hazel would beg me to rest. But I was controlled by the weather: If it was sunny, and I needed the sun for a particular image, I simply had to get in the water, as that could be my only opportunity. So it wasn't possible to rest when I physically needed to, but that was merely part of the challenge.

Having Hazel by my side helped enormously to keep motivated to say the least. I simply couldn't have done this without her and she deserves an enormous amount of credit.

The project was so consuming in every aspect--physically, mentally, creatively, emotionally--that frankly it never popped into my head that I should call it quits. I was always thinking about the images, the next state and the research, etc.

Also I was never sure where the next image was going to come from, so it was really exciting to move to the next spot to see what I could find. It was very fast-paced--really a sort of "Around the World in 80 Days" kind of trip.

Q: What was your mission for the project? What do you hope viewers will take away from your images?

AK: My mission was to try and produce at least one image from every state for the book, and to make a visual poem about the waters of America. I hope viewers will take away the fact that there is beauty and wonder in places you wouldn't immediately expect it, and that all water should be cherished and protected.

As Leonardo da Vinci said, "Water is the driving force of all nature."

Q: What role do you see yourself playing--spectator, reporter, artist or activist?

AK: All of the above, but primarily an artist.

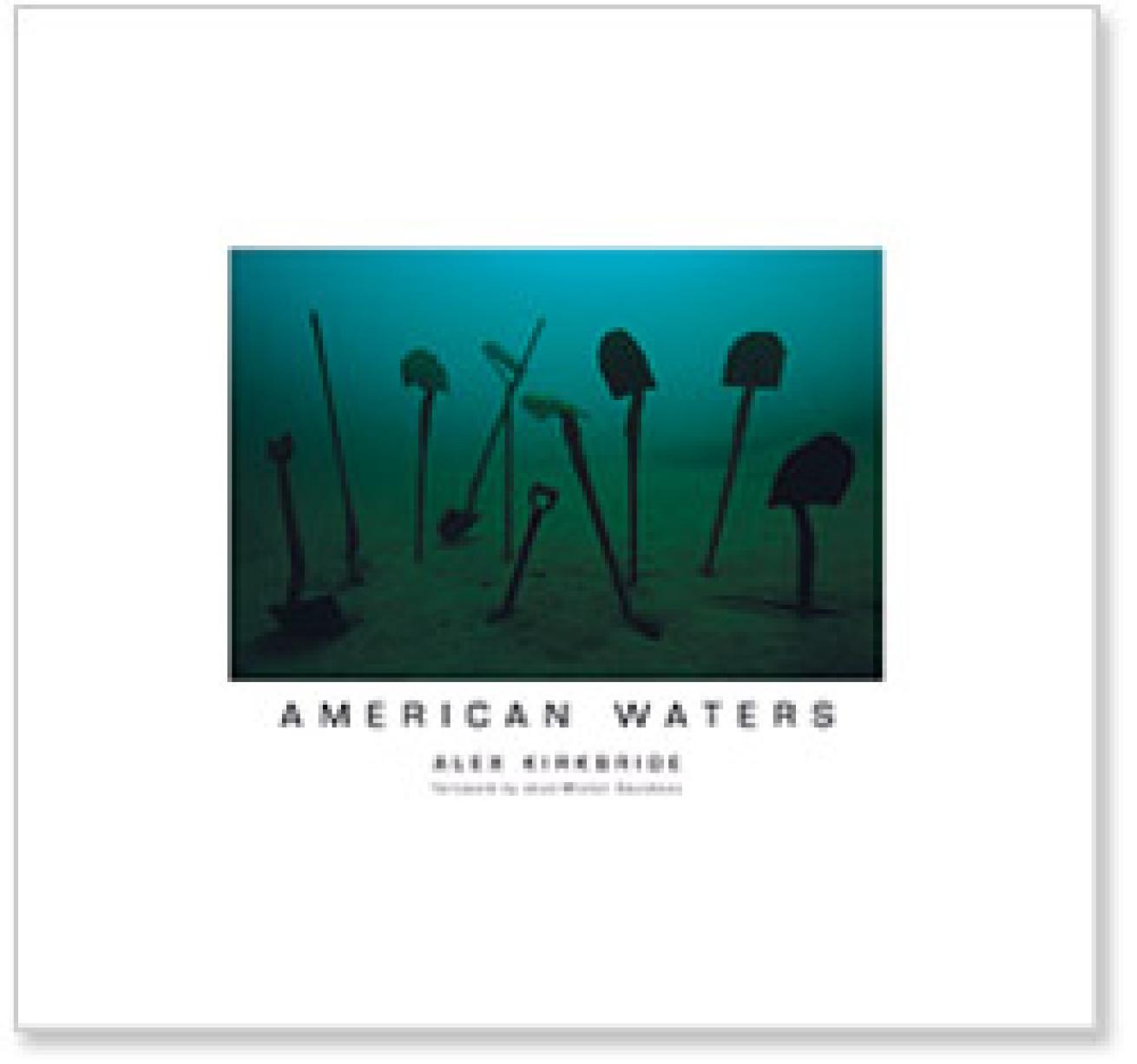

Q: Your images capture both natural and manmade objects. Please explain your fascination of seeing both in the image of water?

AK: I was looking at America 200 years after Lewis and Clark had made their epic crossing of the country in search of the Northwest Passage. In that time, human beings have influenced the natural world with industrialization. So I wanted to look at American waters from a modern perspective. Besides that, a great deal of American history is underwater, with all the manmade wrecks--whether it be an old dentist's chair thrown in the water or a disastrous shipwreck.

I was also looking for the unexpected. Manmade objects such as a Titan 1962 nuclear missile certainly fit that bill.

Q: What are some ways in which water changes your approach as a photographer?

AK: You have to work very close to your subject to diminish the diffusing effect of water, so I use wide-angle lens a lot more than I do in a studio, for example. Topside, you can be a long way away. But I like the intimacy of being close. It creates a better interaction.

You don't have as much time as when you're shooting topside, so your decision-making process has to be quicker. I ask a lot of questions before I jump in the water to minimize lost time wandering around looking for a decent composition or a particular animal. If someone is around to show me where to go, that's great, but I didn't have that luxury a lot of the time on the trip.

Q: What were some of the more challenging aspects of capturing these images (e.g., wildlife, conditions)?

AK: I was working in so many different foreign environments, it was a real challenge to understand a particular area quickly, peel back the visual layers and try to make a well-composed photographic statement.

Dealing with silty bottoms in freshwater was particularly tricky, especially when I was using a tripod. My buoyancy control had to be spot on so I didn't ruin a photograph.

Trying to coordinate being in a particular area when the visibility was at its optimum or near its optimum was a minefield.

Constantly dealing with wildlife I didn't know very well, or at all, and had to learn on the spot how to approach. For example photographing a loon in Minnesota.

Q: What were some of the more challenging aspects of the trip itself?

AK: Finding at least one image for every inland state and doing the research to find them. Making decision after decision about where to go, questioning whether you made the right decision. Frustration when you moved to an area you thought would yield an image but didn't, and the absolute joy when an idea you had in your mind actually worked.

Working and living with your partner 24/7 with little social life and very few distractions, and not seeing your friends or family. We were in our own little bubble.

I had to keep my mind open creatively at all times. The driving and the miles we covered every month were tiring, which made it tougher to think clearly and react quickly underwater when I had to.

Constantly trying to second-guess the weather. This was particularly tricky during the very active 2004 hurricane season. That was the one time when I lost far too many diving days.

Q: Which sites stand out in your mind or haunt your memory?

AK: So many stand out in my mind, because I jumped into such a variety of water environments, and each image has a different story behind it.

Having a humpback whale eyeball me from a short distance away was incredibly special and humbling. Watching sea lions swarm around me at Santa Barbara Island was a joy. Lying in a cranberry bog was surreal and the visibility at Clear Lake in Oregon was mind-boggling. Seeing a German U boat (U-352) almost completely intact at the bottom of the ocean off the coast of North Carolina was like going back in time. And it was amazing to have Havasu Falls all to ourselves for a day. I loved my exploratory dives in Alaska also. I could go on and on.

The cemetery at Lake Jocassee was very eerie and haunting, as the light level was so low at 132 feet. We passed over a few graves that had been exhumed--all that was left were perfect rectangular holes.

Q: What is your basic can't-live-without-it camera setup?

AK: I haven't gone digital yet. American Waters was all shot on Professional Kodak E100GX 35mm film. So for the moment, my can't-live-without setup would be a Nexus F4 housing, a Nikon F4 with a large action viewfinder and a wide-angle lens, either a 16mm or 18mm.

Q: What remains your biggest hurdle as an underwater photographer? What are you driven to perfect?

AK: Money to go do what I would like to...and time.

It takes a lot of money to get off the beaten track for a decent period of time when you're not sent somewhere by a magazine.

And enough time underwater. Ideally, I would like to spend a lot more time underwater every year than I do. This project was obviously the exception to the rule.

I'm driven to find unusual images that might make people stop and think for a moment.

Q: What advice would you offer a diver seeking to become a better underwater photographer?

AK: Perfect your diving skills, especially buoyancy. Your equipment should feel like a second skin. Get a lot of dives under your belt before you even take a camera underwater. I was lucky, as I had hundreds of dives as a divemaster before I took a camera down.

Know your subject. If it is an animal, do your research.

Don't try and shoot too many subjects when you're underwater. Concentrate on only a few per dive at the very most. I'm lucky if I find one! Find your subject and then work it, don't just snap and move on. Compose your shot and then wait and see. It's surprising what happens or what comes along if you remain in one place for a while. Use the available light, be very patient and don't be afraid to experiment.

Q: You met your wife, Hazel, during the early part of this project. What other transforming events did you experience?

AK: At the beginning of the project I was concerned about spending so many years on one idea. But once I began, I felt that what I was doing was absolutely the right thing. I have never felt that clear before in my career.

Apart from that, dealing with the hurricanes and tropical storms during the summer of 2004 made me realize even more how incredibly fragile life is on this planet.

Q: Is Hazel an underwater photography widow? Do you ever leave your camera topside?

AK: Hazel is an underwater photography widow, but she is also a new diver who likes warm water. Most of the time I was in the water she was my topside assistant, changing film and doing production work.

No, I never leave my camera topside because you never know what might appear.

Q: What's next? Do you plan any similarly themed trips to other regions of the world?

AK: After five years of working nonstop and having very little time for anything but the project, I would like to take Hazel on a holiday, spend some quality time with my family, and just sit and reflect without a deadline looming.

I have quite a few ideas in the pipeline, one very long-term one and many shorter ideas, but I'm not sure which idea I will pursue next.

Alex Kirkbride

The underwater photographer and author of American Waters shares the inspiration for his three-year, 108,000-mile odyssey to document this nation's myriad waterways.

Q: You live in Hove, England, yet you chose to focus your project on American waters. Why?

Alex Kirkbride: I am actually a native New Yorker. I spent the first six years of my life in the U.S., and then we moved to England, where I lived until I was 22. So I grew up with an American mother in London, with both American and English cultures, and have always felt torn between both countries. From 25 to 42, I lived in New York City and felt it was time to move back to the UK. But I wanted to say something about America before I returned, something that hadn't been said before photographically--something substantial enough for me to feel OK about leaving the States.

Q: How did you get your start in photography?

AK: I began to learn underwater photography in 1982 by taking pictures at night when I wasn't in charge of a night dive as a divemaster at the Riding Rock Inn, San Salvador, Bahamas. Then, part of my job at the Rum Cay Club, Rum Cay, Bahamas, was to take photographs of the guests underwater. At the same time I took a correspondence course from a photography school in New York. The course taught me the fundamentals and the rest I picked up by trial and error. After a while I had accumulated enough images to make a slide show. A few professional photographers came down and remarked on my work. Initially, I just thought they were all being polite! However, one pro came back the next year and remarked on my improvement. At this point I realized that I could have the ability to pursue photography as a career. So instead of going to photography school, I became an assistant for five years in New York City before I started my own business.

Q: What about diving compels you as a form of exploration and discovery?

AK: To see places few people have had the chance to see and the opportunity through photography to show people what is down there. I feel very fortunate to be able to do this.

Q: You took 848 days to complete this project, covered more than 100,000 miles, went on 945 dives and spent some 732 hours underwater. How did you keep motivated?

AK: I had wanted to make a book since I was 12 years old, so it wasn't too hard to keep motivated. I felt this was my opportunity and I wasn't going to let it pass, especially after having been forced to delay the project for two years due to illness. However, there were times when it was tough to keep motivated. But then I would meet someone who was genuinely enthusiastic and excited about what I was trying to accomplish. This enthusiasm, which I was surprised happened time and time again, encouraged and inspired me.

Apart from that, sheer determination and willpower, perseverance, fear of failure and running on adrenaline.

I'm glad to say I was able to rise to the challenge, as I honestly didn't know at the beginning if I was going to be able to keep up. There were days when I felt I couldn't get in the water from exhaustion, and Hazel would beg me to rest. But I was controlled by the weather: If it was sunny, and I needed the sun for a particular image, I simply had to get in the water, as that could be my only opportunity. So it wasn't possible to rest when I physically needed to, but that was merely part of the challenge.

Having Hazel by my side helped enormously to keep motivated to say the least. I simply couldn't have done this without her and she deserves an enormous amount of credit.

The project was so consuming in every aspect--physically, mentally, creatively, emotionally--that frankly it never popped into my head that I should call it quits. I was always thinking about the images, the next state and the research, etc.

Also I was never sure where the next image was going to come from, so it was really exciting to move to the next spot to see what I could find. It was very fast-paced--really a sort of "Around the World in 80 Days" kind of trip.

Q: What was your mission for the project? What do you hope viewers will take away from your images?

AK: My mission was to try and produce at least one image from every state for the book, and to make a visual poem about the waters of America. I hope viewers will take away the fact that there is beauty and wonder in places you wouldn't immediately expect it, and that all water should be cherished and protected.

As Leonardo da Vinci said, "Water is the driving force of all nature."

Q: What role do you see yourself playing--spectator, reporter, artist or activist?

AK: All of the above, but primarily an artist.

Q: Your images capture both natural and manmade objects. Please explain your fascination of seeing both in the image of water?

AK: I was looking at America 200 years after Lewis and Clark had made their epic crossing of the country in search of the Northwest Passage. In that time, human beings have influenced the natural world with industrialization. So I wanted to look at American waters from a modern perspective. Besides that, a great deal of American history is underwater, with all the manmade wrecks--whether it be an old dentist's chair thrown in the water or a disastrous shipwreck.

I was also looking for the unexpected. Manmade objects such as a Titan 1962 nuclear missile certainly fit that bill.

Q: What are some ways in which water changes your approach as a photographer?

AK: You have to work very close to your subject to diminish the diffusing effect of water, so I use wide-angle lens a lot more than I do in a studio, for example. Topside, you can be a long way away. But I like the intimacy of being close. It creates a better interaction.

You don't have as much time as when you're shooting topside, so your decision-making process has to be quicker. I ask a lot of questions before I jump in the water to minimize lost time wandering around looking for a decent composition or a particular animal. If someone is around to show me where to go, that's great, but I didn't have that luxury a lot of the time on the trip.

Q: What were some of the more challenging aspects of capturing these images (e.g., wildlife, conditions)?

AK: I was working in so many different foreign environments, it was a real challenge to understand a particular area quickly, peel back the visual layers and try to make a well-composed photographic statement.

Dealing with silty bottoms in freshwater was particularly tricky, especially when I was using a tripod. My buoyancy control had to be spot on so I didn't ruin a photograph.

Trying to coordinate being in a particular area when the visibility was at its optimum or near its optimum was a minefield.

Constantly dealing with wildlife I didn't know very well, or at all, and had to learn on the spot how to approach. For example photographing a loon in Minnesota.

Q: What were some of the more challenging aspects of the trip itself?

AK: Finding at least one image for every inland state and doing the research to find them. Making decision after decision about where to go, questioning whether you made the right decision. Frustration when you moved to an area you thought would yield an image but didn't, and the absolute joy when an idea you had in your mind actually worked.

Working and living with your partner 24/7 with little social life and very few distractions, and not seeing your friends or family. We were in our own little bubble.

I had to keep my mind open creatively at all times. The driving and the miles we covered every month were tiring, which made it tougher to think clearly and react quickly underwater when I had to.

Constantly trying to second-guess the weather. This was particularly tricky during the very active 2004 hurricane season. That was the one time when I lost far too many diving days.

Q: Which sites stand out in your mind or haunt your memory?

AK: So many stand out in my mind, because I jumped into such a variety of water environments, and each image has a different story behind it.

Having a humpback whale eyeball me from a short distance away was incredibly special and humbling. Watching sea lions swarm around me at Santa Barbara Island was a joy. Lying in a cranberry bog was surreal and the visibility at Clear Lake in Oregon was mind-boggling. Seeing a German U boat (U-352) almost completely intact at the bottom of the ocean off the coast of North Carolina was like going back in time. And it was amazing to have Havasu Falls all to ourselves for a day. I loved my exploratory dives in Alaska also. I could go on and on.

The cemetery at Lake Jocassee was very eerie and haunting, as the light level was so low at 132 feet. We passed over a few graves that had been exhumed--all that was left were perfect rectangular holes.

Q: What is your basic can't-live-without-it camera setup?

AK: I haven't gone digital yet. American Waters was all shot on Professional Kodak E100GX 35mm film. So for the moment, my can't-live-without setup would be a Nexus F4 housing, a Nikon F4 with a large action viewfinder and a wide-angle lens, either a 16mm or 18mm.

Q: What remains your biggest hurdle as an underwater photographer? What are you driven to perfect?

AK: Money to go do what I would like to...and time.

It takes a lot of money to get off the beaten track for a decent period of time when you're not sent somewhere by a magazine.

And enough time underwater. Ideally, I would like to spend a lot more time underwater every year than I do. This project was obviously the exception to the rule.

I'm driven to find unusual images that might make people stop and think for a moment.

Q: What advice would you offer a diver seeking to become a better underwater photographer?

AK: Perfect your diving skills, especially buoyancy. Your equipment should feel like a second skin. Get a lot of dives under your belt before you even take a camera underwater. I was lucky, as I had hundreds of dives as a divemaster before I took a camera down.

Know your subject. If it is an animal, do your research.

Don't try and shoot too many subjects when you're underwater. Concentrate on only a few per dive at the very most. I'm lucky if I find one! Find your subject and then work it, don't just snap and move on. Compose your shot and then wait and see. It's surprising what happens or what comes along if you remain in one place for a while. Use the available light, be very patient and don't be afraid to experiment.

Q: You met your wife, Hazel, during the early part of this project. What other transforming events did you experience?

AK: At the beginning of the project I was concerned about spending so many years on one idea. But once I began, I felt that what I was doing was absolutely the right thing. I have never felt that clear before in my career.

Apart from that, dealing with the hurricanes and tropical storms during the summer of 2004 made me realize even more how incredibly fragile life is on this planet.

Q: Is Hazel an underwater photography widow? Do you ever leave your camera topside?

AK: Hazel is an underwater photography widow, but she is also a new diver who likes warm water. Most of the time I was in the water she was my topside assistant, changing film and doing production work.

No, I never leave my camera topside because you never know what might appear.

Q: What's next? Do you plan any similarly themed trips to other regions of the world?

AK: After five years of working nonstop and having very little time for anything but the project, I would like to take Hazel on a holiday, spend some quality time with my family, and just sit and reflect without a deadline looming.

I have quite a few ideas in the pipeline, one very long-term one and many shorter ideas, but I'm not sure which idea I will pursue next.