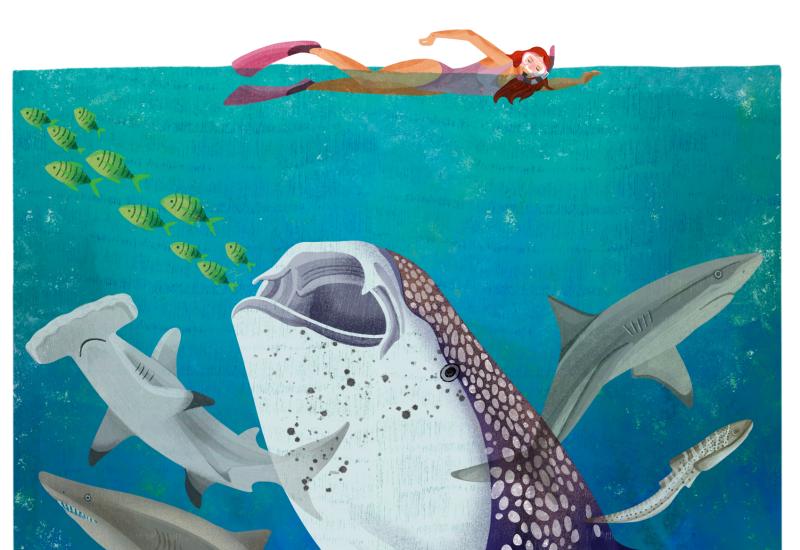

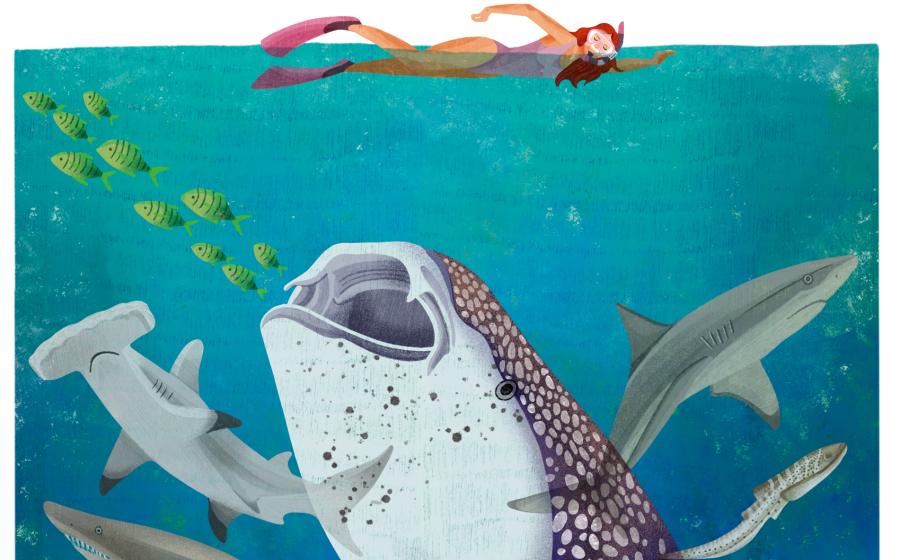

Should Big Animals Live in Aquariums?

Aquariums

Aquariums support conservation and promote education through meaningful encounters

By Bruce Carlson

I am seated in front of a massive window that holds back 6.3 million gallons of sea water at the Georgia Aquarium in Atlanta. It’s a Thursday afternoon and about 125 people are in this gallery, including several dozen children seated on the floor, mesmerized by the amazing creatures just on the other side of the glass. We are watching two whale sharks being fed while a narrator explains that they are plankton feeders. The kids are enthralled; not only by the whale sharks, but also by the thousands of other animals they have access to in these exhibits. During the past five years, more than 11 million people have had this same experience. I am certain that more than just one of the millions of children who have been here will decide to dedicate their lives to marine biology and conservation as a result of their trip to the aquarium.

Scuba Diving readers are among the lucky few who have seen and interacted with the magnificent creatures that live in the ocean. An even smaller group has had up-close encounters with the largest animals in the sea: whales, dolphins, whale sharks and manta rays. These encounters are unpredictable and brief, yet they are experiences that make a lifelong impression on the people who have them. And not only does the sport of diving require specific training and physical prowess, the trips to dive in the places where these most interesting creatures live cost a considerable sum. Airfare, boat charters, gear rentals and more make these encounters a luxury many people cannot afford. But thanks to places like the Georgia Aquarium, the thrill of seeing a whale shark or a manta ray is no longer an exclusive experience, but rather an accessible encounter for the masses.

What aquariums and zoos do best is help bring people and animals closer together. And the more we learn about animals, the more we care about them and their environments. So how could a place like this not encourage people to be active in the conservation of these creatures? As I write this, I can see the impact of this tremendous educational and empowering experience in the eyes of these young children.

But the impact goes beyond education. The revenue generated from guest attendance at many zoological parks and aquariums around the world is used to support research and conservation. For instance, since 2003 the Georgia Aquarium has provided research grants to scientists in the U.S. and Mexico to document the aggregation of whale sharks that appears each year off the town of Holbox on the Yucatan peninsula. More than 700 whale sharks have been tagged and photographed, and over many years this data will give us a good understanding of population dynamics of whale sharks in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean. Aerial surveys funded by the aquarium have also contributed valuable data on where to establish boundaries for the new Whale Shark Biosphere Preserve created in Holbox in 2009. The new preserve will help protect whale sharks from possible exploitation and ensure that their food supply –– plankton and fish eggs –– is not endangered from pollution.

This is just one example of how aquariums give back to nature. Over the past five years, aquariums and zoos accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums have provided nearly $89 million to more than 3,700 conservation projects all over the world. These programs for species ranging from tiny Banggai cardinal fish in Indonesia to great white sharks off California to beluga whales in Alaska are giving the animals a better chance to thrive in the wild.

When people ask me whether or not large animals, like whale sharks, should be kept in aquariums or zoos, I tell them to ask the children at the aquarium that day. I am sure they would give you a resounding “yes.” The awe they are feeling will turn into appreciation and respect for living creatures they might otherwise have never known.

Bruce Carlson is the Chief Science Officer at the Georgia Aquarium. A diver since 1967, he is also the former Director of the Waikiki Aquarium in Honolulu.

Large Marine Animals Do Not Belong in Bath Tubs

By Kim McCoy

Captive marine animals are often referred to as “ambassadors for their kind,” as though they have some choice in the matter or this is somehow a noble pursuit. My question is always: What did these innocent beings do to deserve the extreme trauma of a potentially lethal wild capture (yes, these still happen routinely around the world) followed by a life sentence in a liquid prison that is unnatural in every conceivable way; an environment rife with stress, boredom, frustration of natural instincts, forced human interactions, increased mortality rates and decreased quality of life? Wouldn’t they be much better ambassadors in the wild?

With startlingly few exceptions, most aquariums worldwide (and certainly entities such as casinos and marine “abusement” parks) exist exclusively for the purpose of generating profits through commercial exploitation. Animals are regarded as expendable commodities, high death and illness rates are anticipated costs of doing business, and the underlying message is that confinement of animals for profit and human entertainment is acceptable.

While nearly all aquariums attempt to justify this exploitation under the guise of conservation, education and research, only a tiny percentage actually conduct legitimate conservation programs. Even then, the money spent on conservation represents a fraction of the overall income generated off the backs of these animals and begs the question: Wouldn’t the money spent finding ways to keep animals alive in artificial environments be better spent solving conservation issues in their natural habitats in the first place?

The standard argument is that aquariums are necessary because they educate people and create awareness of the plight of wild animals, resulting in a call to action. But there is no solid evidence that viewing captive animals translates directly into any sort of practical conservation action. To the contrary, viewing animals in unnaturally small, often chlorinated enclosures desensitizes people to the cruelty inherent in their removal from the wild. It encourages the false notion of animals in isolation that are dependent upon humans for survival, rather than integral elements of ocean ecosystems that are fully competent to care for themselves. More important, it discourages the correct view of marine animals as sentient beings with their own intrinsic value, deserving of the right to live their lives free from human interference.

Aquariums and the research conducted therein teach us nothing of migratory or foraging patterns, actual life spans or complex natural behaviors exhibited by large marine animals in the wild. How, for example, is a young child supposed to learn, by looking into a concrete and Plexiglas enclosure only 30 feet deep, that whale sharks routinely dive to almost 5,000 feet? That child sees an animal swimming in endless circles. Whale sharks can live for up to 150 years in the wild, yet we applaud facilities that can keep them alive for three to 10 years in captivity, as if that is somehow an accomplishment.

No man-made enclosure can adequately simulate the tides, the biodiversity, or the sheer vastness and freedom of the open ocean in order to meet the complex physical and psychological needs of large captive animals. Enclosures are designed for human convenience and comfort, not the animals’ well being, and even the best-designed enclosures frustrate and confuse critical senses relied upon in the wild for navigation, danger avoidance or locating prey, such as dolphin echolocation or a shark’s ability to detect and interpret vibrations and electrical activity.

While it is legitimate to conclude that some facilities are more or less damaging than others, the lives led by large captive marine animals are so contrary to the natural experiences of their wild counterparts — and the purported benefits of confinement are such a stretch — that it is simply unforgivable to keep these animals in captivity.

Wouldn’t we all be much better off funneling the billions of dollars spent supporting commercial captive enterprises into learning about our oceans through more compassionate and accurate means, such as observation in the wild (with responsible operators), virtual reality simulations, books, DVDs and/or IMAX theatres? Don’t we owe it to our children, to the animals and to our planet to move forward in a way that inflicts no harm?

Kim McCoy is the Director of Campaigns for Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, a nonprofit organization specializing in international ocean wildlife conservation. She is also a co-founder of the Shark Angels alliance.

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.com

Should sharks, killer whales and other marine animals be kept in aquariums? Scroll down to read two different perspectives from industry experts.

Shutterstock

Aquariums support conservation and promote education through meaningful encounters

By Bruce Carlson

I am seated in front of a massive window that holds back 6.3 million gallons of sea water at the Georgia Aquarium in Atlanta. It’s a Thursday afternoon and about 125 people are in this gallery, including several dozen children seated on the floor, mesmerized by the amazing creatures just on the other side of the glass. We are watching two whale sharks being fed while a narrator explains that they are plankton feeders. The kids are enthralled; not only by the whale sharks, but also by the thousands of other animals they have access to in these exhibits. During the past five years, more than 11 million people have had this same experience. I am certain that more than just one of the millions of children who have been here will decide to dedicate their lives to marine biology and conservation as a result of their trip to the aquarium.

Scuba Diving readers are among the lucky few who have seen and interacted with the magnificent creatures that live in the ocean. An even smaller group has had up-close encounters with the largest animals in the sea: whales, dolphins, whale sharks and manta rays. These encounters are unpredictable and brief, yet they are experiences that make a lifelong impression on the people who have them. And not only does the sport of diving require specific training and physical prowess, the trips to dive in the places where these most interesting creatures live cost a considerable sum. Airfare, boat charters, gear rentals and more make these encounters a luxury many people cannot afford. But thanks to places like the Georgia Aquarium, the thrill of seeing a whale shark or a manta ray is no longer an exclusive experience, but rather an accessible encounter for the masses.

What aquariums and zoos do best is help bring people and animals closer together. And the more we learn about animals, the more we care about them and their environments. So how could a place like this not encourage people to be active in the conservation of these creatures? As I write this, I can see the impact of this tremendous educational and empowering experience in the eyes of these young children.

But the impact goes beyond education. The revenue generated from guest attendance at many zoological parks and aquariums around the world is used to support research and conservation. For instance, the Georgia Aquarium has provided research grants to scientists in the U.S. and Mexico to document the aggregation of whale sharks that appears each year off the town of Holbox on the Yucatan peninsula. From 2003-2010, more than 700 whale sharks were tagged and photographed, and over many years this data will give us a good understanding of population dynamics of whale sharks in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean. Aerial surveys funded by the aquarium have also contributed valuable data on where to establish boundaries for the new Whale Shark Biosphere Preserve created in Holbox in 2009. The new preserve will help protect whale sharks from possible exploitation and ensure that their food supply –– plankton and fish eggs –– is not endangered from pollution.

This is just one example of how aquariums give back to nature. Over from 2005-2010, aquariums and zoos accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums provided nearly $89 million to more than 3,700 conservation projects all over the world. These programs for species ranging from tiny Banggai cardinal fish in Indonesia to great white sharks off California to beluga whales in Alaska are giving the animals a better chance to thrive in the wild.

When people ask me whether or not large animals, like whale sharks, should be kept in aquariums or zoos, I tell them to ask the children at the aquarium that day. I am sure they would give you a resounding “yes.” The awe they are feeling will turn into appreciation and respect for living creatures they might otherwise have never known.

Bruce Carlson was the Chief Science Officer at the Georgia Aquarium from 2002-2011. A diver since 1967, he is also the former Director of the Waikiki Aquarium in Honolulu.

Large Marine Animals Do Not Belong in Bath Tubs

By Kim McCoy

Captive marine animals are often referred to as “ambassadors for their kind,” as though they have some choice in the matter or this is somehow a noble pursuit. My question is always: What did these innocent beings do to deserve the extreme trauma of a potentially lethal wild capture (yes, these still happen routinely around the world) followed by a life sentence in a liquid prison that is unnatural in every conceivable way; an environment rife with stress, boredom, frustration of natural instincts, forced human interactions, increased mortality rates and decreased quality of life? Wouldn’t they be much better ambassadors in the wild?

With startlingly few exceptions, most aquariums worldwide (and certainly entities such as casinos and marine “abusement” parks) exist exclusively for the purpose of generating profits through commercial exploitation. Animals are regarded as expendable commodities, high death and illness rates are anticipated costs of doing business, and the underlying message is that confinement of animals for profit and human entertainment is acceptable.

While nearly all aquariums attempt to justify this exploitation under the guise of conservation, education and research, only a tiny percentage actually conduct legitimate conservation programs. Even then, the money spent on conservation represents a fraction of the overall income generated off the backs of these animals and begs the question: Wouldn’t the money spent finding ways to keep animals alive in artificial environments be better spent solving conservation issues in their natural habitats in the first place?

The standard argument is that aquariums are necessary because they educate people and create awareness of the plight of wild animals, resulting in a call to action. But there is no solid evidence that viewing captive animals translates directly into any sort of practical conservation action. To the contrary, viewing animals in unnaturally small, often chlorinated enclosures desensitizes people to the cruelty inherent in their removal from the wild. It encourages the false notion of animals in isolation that are dependent upon humans for survival, rather than integral elements of ocean ecosystems that are fully competent to care for themselves. More important, it discourages the correct view of marine animals as sentient beings with their own intrinsic value, deserving of the right to live their lives free from human interference.

Aquariums and the research conducted therein teach us nothing of migratory or foraging patterns, actual life spans or complex natural behaviors exhibited by large marine animals in the wild. How, for example, is a young child supposed to learn, by looking into a concrete and Plexiglas enclosure only 30 feet deep, that whale sharks routinely dive to almost 5,000 feet? That child sees an animal swimming in endless circles. Whale sharks can live for up to 150 years in the wild, yet we applaud facilities that can keep them alive for three to 10 years in captivity, as if that is somehow an accomplishment.

No man-made enclosure can adequately simulate the tides, the biodiversity, or the sheer vastness and freedom of the open ocean in order to meet the complex physical and psychological needs of large captive animals. Enclosures are designed for human convenience and comfort, not the animals’ well being, and even the best-designed enclosures frustrate and confuse critical senses relied upon in the wild for navigation, danger avoidance or locating prey, such as dolphin echolocation or a shark’s ability to detect and interpret vibrations and electrical activity.

While it is legitimate to conclude that some facilities are more or less damaging than others, the lives led by large captive marine animals are so contrary to the natural experiences of their wild counterparts — and the purported benefits of confinement are such a stretch — that it is simply unforgivable to keep these animals in captivity.

Wouldn’t we all be much better off funneling the billions of dollars spent supporting commercial captive enterprises into learning about our oceans through more compassionate and accurate means, such as observation in the wild (with responsible operators), virtual reality simulations, books, DVDs and/or IMAX theatres? Don’t we owe it to our children, to the animals and to our planet to move forward in a way that inflicts no harm?

Kim McCoy is the Executive Director of Big Life Foundation, and was the Director of Campaigns for Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, a nonprofit organization specializing in international ocean wildlife conservation, from 2007-2009.

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.com

Editor's Note: This story was originally published in Scuba Diving magazine in 2010.