Mastering the Muck

Text and Photography by Stephen Frink

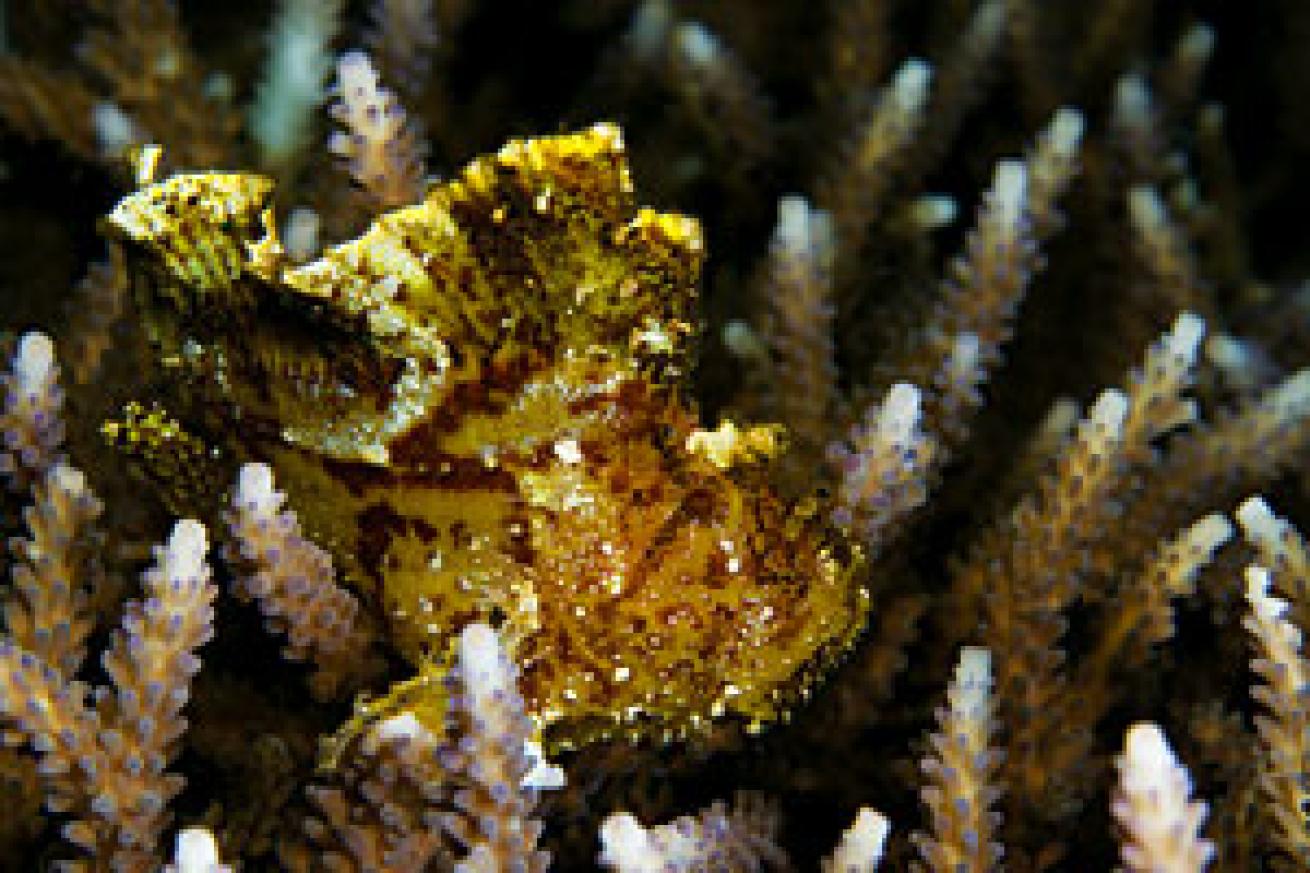

Muck photography: You're diving in 20 feet of water with marginal visibility--sometimes with more than a fair bit of garbage strewn about--shooting microscopic creatures that are hard to find and even harder to shoot. Doesn't sound sexy, does it? And it definitely doesn't sound like something divers would spend thousands of dollars on and travel halfway around the world to experience. Yet, that's exactly what we do, and photography in far-flung destinations known for their cryptic creatures of the muck is all the rage. In the Caribbean, divers long ago learned to look past the tires, bottles and tennis shoes cluttering the seafloor beneath Bonaire's Town Pier because we've realized the pilings, cloaked with orange cup corals and tube sponges, are a rich habitat. They provide refuge for seahorses, frogfish, high-hats and juveniles of many reef species. St. Vincent has likewise attracted fanatic fanboys eager to capture its weird and wonderful flying gurnards, scorpionfish, peacock flounders and bull's-eye lobster.

But the big action in muck photography happens far, far away, in exotic locales such as Tulamben Bay, Raja Ampat and Lembeh Strait, Indonesia; Milne Bay, Papua New Guinea; and Mabul, Malaysia. These are the iconic muck destinations that shooters passionately put on their must-dive list, and these sites consistently deliver some of the most bizarre and colorful images in underwater photography. Want to master the muck? Here's how:

The Tools

Most of the creatures at muck sites are reasonably small, making a 50mm or 100mm macro lens for Canons with full-frame sensors, or 60mm and 105mm Micro-Nikkors for cropped-sensor Nikons, the go-to lenses for most circumstances. And because the most interesting muck critters are often the tiniest ones, a high magnification is a must--use a lens with at least 1:1 magnification (life-size). Extension tubes or threaded close-up lenses can be applied to the lens (inside the housing). Of course, then your entire dive will be devoted to nothing but very small creatures, but this is a useful discipline--it forces selective vision, as all subjects larger than the size of a dime are pretty well excluded from consideration. A more versatile approach is using an external close-up lens--like the Backscatter Macro-Mate, Nexus Wet Diopter or the Seacam Wet Two--that slips over the front of the macro port as needed when ultra-small subjects are discovered. The Macro-Mate offers the greatest magnification, about twice life-size, while the other wet diopters probably add another 25 to 40 percent magnification when installed.

You can also encounter larger animals in these areas, however, and a system that offers flexibility can be useful if you're looking for a range of subjects. For example, I could have the best shot of the octopus (#2 right) with my 16-35mm zoom lens. With the 100mm macro I had mounted at the time, I had to crop extra-tight and force the composition to fit the lens. It worked out, but if I'd had the choice, I would've used a different lens. I was rather envious of my dive buddy who was shooting a Sea and Sea compact DX-1G on the same dive. I watched as she took a series of portraits of the octopus, navigated into macro mode and got some shots of the eye, and then added her wide-angle accessory lens to the front of the housing and got wonderful environmental shots of the octopus free-swimming along the reef. For additional macro tips and techniques, see stephenfrink.com/sf-tips/200601-macro-techniques.

Backscatter Control

Muck environments aren't necessarily crystalline. In fact, most are near shore and can suffer visibility degradation from rain runoff or detritus stirred up by surge. Plus, they often have sand bottoms rather than hard-coral reefs or walls, so sloppy buoyancy control and errant fin kicks can step on visibility in an already challenging situation. The good thing is that most of these subjects aren't in open water, and bits of backscatter are often obscured by the visual confusion of the background. For example, this mimic octopus (#3 right) was swimming along the volcanic sand bottom off Lembeh. I only had about 25 feet of visibility, but because I shot at a downward angle, the sandy bottom camouflaged the chunks of particulate illuminated by the strobe.

The most challenging shots are dark subjects with open-water elements--this is where backscatter really shows up--and sometimes backscatter is inevitable in the muck. These catfish (#4 right) were found in marginal visibility to begin with, and like a rowdy group of teenagers, they went from spot to spot along the reef, stirring up even more debris wherever they went with their boisterous feeding habits. Do your best to avoid backscatter by choosing visually confusing backgrounds and using various lighting angles, but sometimes the cloning tools in Photoshop and a healthy dose of elbow grease are your best bet for eliminating backscatter.

The Role of the Dive Guide

While I'm sure there are plenty of shooters who can find subjects themselves, a good local divemaster knows the habits of minute and highly camouflaged marine life, where they live and how to best present them to the macro lenses of their visiting photographers. I'll be the first to admit this pygmy seahorse shot (#5 right) greatly depended on a guide to point it out to me in the first place. It was a challenge to get such a small creature reasonably large in the frame, as was trying to shoot it facing toward the lens when its naturally frustrating inclination is to turn away. Because the composition work alone takes valuable time in 60 to 80 feet of water, having a knowledgeable dive guide really minimized the bottom time we spent searching and maximized my pygmy photo-ops.

The best critter finders are highly desired photo facilitators, able to move from spot to spot along a muck site, pointing their little metal wands to setup after setup. By the time a photographer is done with one amazing macro discovery, the guide has often already found the next one. Is it cheating? I don't think so. Even Tiger Woods uses a coach to help him refine his golf swing. Of course, the analogy fails in that Tiger can find all 18 holes by himself. But, these guides do have very special skills and incredible visual acuity, and a muck photographer will increase his or her efficiency by relying on local knowledge. Many of these creatures are reasonably sedentary, and the guides will know where they found them the week before. Plus, guides freely share information with one another. If one guide on the morning boat finds a cuttlefish laying eggs in the elkhorn, the dive guides on the afternoon boat will go out armed with that knowledge.

Not All Muck is Created Equal

I've sometimes thought muck diving must be one of the grand pranks in scuba diving, perpetrated by eagle-eyed divemasters who discovered that by pointing out a pygmy seahorse, a shrimp on a sea cucumber or a mandarinfish along an otherwise uninteresting reefscape, they can ignite a firestorm of flashes from their grateful customers and as a result generate ever greater gratuities. Certainly the world's muck diving hot spots offer up incredible photo ops, often unique to that particular spot, but all muck sites are definitely not created equal. I had to chuckle at a recent web post by photographer Matthew Addison who described his most memorable muck dive destination:

"We spent two days at a 'muck' site at the request of the macro shooters amongst us. This is not the volcanic muck one finds in places such as Lembeh. This is the runoff of a town with no sewage system. I called it quits after day one when a dead, bloated dog floating by was pointed out to me. The other shooters were braver than I and only called it quits when several dump trucks of 'poop' were dumped over their heads. Some of the townspeople standing on the dock doubled over with laughter. No kidding, this really happened!"

I'm not suggesting good muck dives can't be done in sewage outflows--who knows what kind of strange mutant life we might find there--but in my experience, the best muck dives are those where the habitats sustain a wide variety of small and fascinating marine life, and where dive guides have well-honed skills in pointing out these creatures of desire to their visually challenged guests.

Muck Etiquette

Because muck diving attracts eager and aggressive photographers who often spend large sums of cash and time to get to these spots, you and your fellow divers may feel a strong urge to get the shot no matter what. To help you keep sight of what's important, namely the sustainability of the environment and your reputation as a photographer people will want to dive with, here are four tips for minding your manners in the muck:

Don't monopolize a subject The creature may be extra-sensitive to repeated, close proximity bombardment from a high-powered strobe. Furthermore, another photographer might be patiently waiting nearby to take a turn photographing the same subject. Especially if the dive guide found the subject to begin with, it is common courtesy to let other photographers have their turn.

Don't intrude on a photo setup Particularly in a muck environment, repeated strobe flashes will quickly alert you when another shooter in your group finds something interesting. Be patient. It's exceedingly bad form to barge into another photographer's setup, and it's even worse to spook the subject. Stay a healthy distance away and wait your turn. Or, even better, move on to your own shot elsewhere.

Watch your buoyancy and fin kicks Some muck environments are blessed with heavy volcanic sand or rocky substrate, which don't get kicked up easily, but many areas are composed of fine sand or silt where an overweighted or clumsy diver can blunder along the bottom like Pigpen, absolutely obliterating whatever water clarity there might have been. Even worse is the photographer who delicately settles in for a shot, maneuvers with the greatest of care all around the subject for fear of creating backscatter, and then pushes off the bottom with a few hyper-kicks, leaving an impenetrable cloud of silt behind. The generous conclusion here is that diver is unaware or clumsy. The more cynical view is that they purposely trashed the photo-op for the next shooter. Either way, it is tacky.

Don't invite or reward bad behaviors The guides at emerging critter destinations know the better the shot, the more healthy the gratuity. If you reward them, either financially or with excess enthusiasm, for behavior like digging a mimic octopus out of the sand and then dropping it into the water column so you can get the classic shot of the "swimming" octopus, you are only perpetuating bad behavior.

Text and Photography by Stephen Frink

Muck photography: You're diving in 20 feet of water with marginal visibility--sometimes with more than a fair bit of garbage strewn about--shooting microscopic creatures that are hard to find and even harder to shoot. Doesn't sound sexy, does it? And it definitely doesn't sound like something divers would spend thousands of dollars on and travel halfway around the world to experience. Yet, that's exactly what we do, and photography in far-flung destinations known for their cryptic creatures of the muck is all the rage. In the Caribbean, divers long ago learned to look past the tires, bottles and tennis shoes cluttering the seafloor beneath Bonaire's Town Pier because we've realized the pilings, cloaked with orange cup corals and tube sponges, are a rich habitat. They provide refuge for seahorses, frogfish, high-hats and juveniles of many reef species. St. Vincent has likewise attracted fanatic fanboys eager to capture its weird and wonderful flying gurnards, scorpionfish, peacock flounders and bull's-eye lobster.

But the big action in muck photography happens far, far away, in exotic locales such as Tulamben Bay, Raja Ampat and Lembeh Strait, Indonesia; Milne Bay, Papua New Guinea; and Mabul, Malaysia. These are the iconic muck destinations that shooters passionately put on their must-dive list, and these sites consistently deliver some of the most bizarre and colorful images in underwater photography. Want to master the muck? Here's how:

The Tools

Most of the creatures at muck sites are reasonably small, making a 50mm or 100mm macro lens for Canons with full-frame sensors, or 60mm and 105mm Micro-Nikkors for cropped-sensor Nikons, the go-to lenses for most circumstances. And because the most interesting muck critters are often the tiniest ones, a high magnification is a must--use a lens with at least 1:1 magnification (life-size). Extension tubes or threaded close-up lenses can be applied to the lens (inside the housing). Of course, then your entire dive will be devoted to nothing but very small creatures, but this is a useful discipline--it forces selective vision, as all subjects larger than the size of a dime are pretty well excluded from consideration. A more versatile approach is using an external close-up lens--like the Backscatter Macro-Mate, Nexus Wet Diopter or the Seacam Wet Two--that slips over the front of the macro port as needed when ultra-small subjects are discovered. The Macro-Mate offers the greatest magnification, about twice life-size, while the other wet diopters probably add another 25 to 40 percent magnification when installed.

You can also encounter larger animals in these areas, however, and a system that offers flexibility can be useful if you're looking for a range of subjects. For example, I could have the best shot of the octopus (#2 right) with my 16-35mm zoom lens. With the 100mm macro I had mounted at the time, I had to crop extra-tight and force the composition to fit the lens. It worked out, but if I'd had the choice, I would've used a different lens. I was rather envious of my dive buddy who was shooting a Sea and Sea compact DX-1G on the same dive. I watched as she took a series of portraits of the octopus, navigated into macro mode and got some shots of the eye, and then added her wide-angle accessory lens to the front of the housing and got wonderful environmental shots of the octopus free-swimming along the reef. For additional macro tips and techniques, see stephenfrink.com/sf-tips/200601-macro-techniques.

Backscatter Control

Muck environments aren't necessarily crystalline. In fact, most are near shore and can suffer visibility degradation from rain runoff or detritus stirred up by surge. Plus, they often have sand bottoms rather than hard-coral reefs or walls, so sloppy buoyancy control and errant fin kicks can step on visibility in an already challenging situation. The good thing is that most of these subjects aren't in open water, and bits of backscatter are often obscured by the visual confusion of the background. For example, this mimic octopus (#3 right) was swimming along the volcanic sand bottom off Lembeh. I only had about 25 feet of visibility, but because I shot at a downward angle, the sandy bottom camouflaged the chunks of particulate illuminated by the strobe.

The most challenging shots are dark subjects with open-water elements--this is where backscatter really shows up--and sometimes backscatter is inevitable in the muck. These catfish (#4 right) were found in marginal visibility to begin with, and like a rowdy group of teenagers, they went from spot to spot along the reef, stirring up even more debris wherever they went with their boisterous feeding habits. Do your best to avoid backscatter by choosing visually confusing backgrounds and using various lighting angles, but sometimes the cloning tools in Photoshop and a healthy dose of elbow grease are your best bet for eliminating backscatter.

The Role of the Dive Guide

While I'm sure there are plenty of shooters who can find subjects themselves, a good local divemaster knows the habits of minute and highly camouflaged marine life, where they live and how to best present them to the macro lenses of their visiting photographers. I'll be the first to admit this pygmy seahorse shot (#5 right) greatly depended on a guide to point it out to me in the first place. It was a challenge to get such a small creature reasonably large in the frame, as was trying to shoot it facing toward the lens when its naturally frustrating inclination is to turn away. Because the composition work alone takes valuable time in 60 to 80 feet of water, having a knowledgeable dive guide really minimized the bottom time we spent searching and maximized my pygmy photo-ops.

The best critter finders are highly desired photo facilitators, able to move from spot to spot along a muck site, pointing their little metal wands to setup after setup. By the time a photographer is done with one amazing macro discovery, the guide has often already found the next one. Is it cheating? I don't think so. Even Tiger Woods uses a coach to help him refine his golf swing. Of course, the analogy fails in that Tiger can find all 18 holes by himself. But, these guides do have very special skills and incredible visual acuity, and a muck photographer will increase his or her efficiency by relying on local knowledge. Many of these creatures are reasonably sedentary, and the guides will know where they found them the week before. Plus, guides freely share information with one another. If one guide on the morning boat finds a cuttlefish laying eggs in the elkhorn, the dive guides on the afternoon boat will go out armed with that knowledge.

.

Muck Etiquette

Because muck diving attracts eager and aggressive photographers who often spend large sums of cash and time to get to these spots, you and your fellow divers may feel a strong urge to get the shot no matter what. To help you keep sight of what's important, namely the sustainability of the environment and your reputation as a photographer people will want to dive with, here are four tips for minding your manners in the muck:

Don't monopolize a subject The creature may be extra-sensitive to repeated, close proximity bombardment from a high-powered strobe. Furthermore, another photographer might be patiently waiting nearby to take a turn photographing the same subject. Especially if the dive guide found the subject to begin with, it is common courtesy to let other photographers have their turn.

Don't intrude on a photo setup Particularly in a muck environment, repeated strobe flashes will quickly alert you when another shooter in your group finds something interesting. Be patient. It's exceedingly bad form to barge into another photographer's setup, and it's even worse to spook the subject. Stay a healthy distance away and wait your turn. Or, even better, move on to your own shot elsewhere.

Watch your buoyancy and fin kicks Some muck environments are blessed with heavy volcanic sand or rocky substrate, which don't get kicked up easily, but many areas are composed of fine sand or silt where an overweighted or clumsy diver can blunder along the bottom like Pigpen, absolutely obliterating whatever water clarity there might have been. Even worse is the photographer who delicately settles in for a shot, maneuvers with the greatest of care all around the subject for fear of creating backscatter, and then pushes off the bottom with a few hyper-kicks, leaving an impenetrable cloud of silt behind. The generous conclusion here is that diver is unaware or clumsy. The more cynical view is that they purposely trashed the photo-op for the next shooter. Either way, it is tacky.

Don't invite or reward bad behaviors The guides at emerging critter destinations know the better the shot, the more healthy the gratuity. If you reward them, either financially or with excess enthusiasm, for behavior like digging a mimic octopus out of the sand and then dropping it into the water column so you can get the classic shot of the "swimming" octopus, you are only perpetuating bad behavior

Not All Muck is Created Equal

I've sometimes thought muck diving must be one of the grand pranks in scuba diving, perpetrated by eagle-eyed divemasters who discovered that by pointing out a pygmy seahorse, a shrimp on a sea cucumber or a mandarinfish along an otherwise uninteresting reefscape, they can ignite a firestorm of flashes from their grateful customers and as a result generate ever greater gratuities. Certainly the world's muck diving hot spots offer up incredible photo ops, often unique to that particular spot, but all muck sites are definitely not created equal. I had to chuckle at a recent web post by photographer Matthew Addison who described his most memorable muck dive destination:

"We spent two days at a 'muck' site at the request of the macro shooters amongst us. This is not the volcanic muck one finds in places such as Lembeh. This is the runoff of a town with no sewage system. I called it quits after day one when a dead, bloated dog floating by was pointed out to me. The other shooters were braver than I and only called it quits when several dump trucks of 'poop' were dumped over their heads. Some of the townspeople standing on the dock doubled over with laughter. No kidding, this really happened!"

I'm not suggesting good muck dives can't be done in sewage outflows--who knows what kind of strange mutant life we might find there--but in my experience, the best muck dives are those where the habitats sustain a wide variety of small and fascinating marine life, and where dive guides have well-honed skills in pointing out these creatures of desire to their visually challenged guests.