How Scientists are Reducing Bycatch Around the World

Every day, fishermen set thousands of miles of fishing nets and lines in the world’s oceans. But in addition to what it is intended to catch, this gear hauls in a host of unwanted marine life, known in the fishing industry as bycatch. Gill nets hung suspended from the surface in the water column create walls that indiscriminately entangle almost any creature that encounters them. The nets get pulled up, and the bycatch—sea turtles, dolphins, seabirds, or simply the wrong sex, size or species of fish—gets tossed overboard, usually dead or dying.

Some of these animals are considered threatened by extinction, but scientists focused on conserving them face a conundrum: Gill nets are widespread; the culture and food security of many communities depend on this common fishing method, so simply outlawing it is not a solution. That’s why they are now turning to simple, affordable, innovative ways to reduce harm and protect threatened species in fisheries around the globe.

What's That Sound?

An estimated 300,000 porpoises and dolphins per year end up as bycatch globally, 80 percent of them in monofilament or gill nets. For some species, including vaquita in the Gulf of California and right whales off the U.S. East Coast, bycatch is a major contributor to the threat of extinction.

“The animals die in traumatic circumstances that should be avoided if possible,” says Rob Enever, of U.K.-based Fishtek Marine, which develops and produces pinger devices that attach to fishing nets and emit a high-frequency noise when submerged, warding off dolphins and porpoises before they are ensnared and drowned. “No one likes catching a marine mammal. The entanglement can damage expensive fishing nets, resulting in downtime to the fishing operation. I think where fisheries interact with dolphins and porpoises, fishermen should see [pingers] as a basic part of their fishing gear, the same as floats on the net or echo sounders used to measure water depth. They’re simple, effective and inexpensive.”

Pingers such as the ones manufactured by Fishtek Marine are powered with a standard replaceable battery that lasts for approximately six months. The devices themselves typically don’t have to be replaced for at least five years. And what’s more, they seem to be getting results. Enever points to two U.S. fisheries using the devices that reduced porpoise bycatch by 70 percent without diminishing their intended catch.

Enever is one of the authors of a May 2020 article in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science that found pingers effectively reduced capture of several species of cetaceans during a recent study off the English coast of Cornwall. The study looked into possible unintended consequences of using the devices, such as attracting seals that might eat the fishermen’s intended catch or scaring porpoises away from their usual habitats.

The possibility of porpoises getting used to the noise and eventually ignoring it was a main concern, Enever says. If that were the case, fishing operations would spend money on the equipment only to see it become useless over time. But the study showed the porpoises continued to avoid the noise during eight months of testing. In addition, the effect was localized around the devices and the sound did not cause the animals to leave their habitat, suggesting that pingers likely would not have long-term effects on the animal population. The findings should give fisheries managers more confidence in using the devices, Enever says.

“Set-net fisheries have witnessed rapid declines in cetacean populations globally,” he says. “The luxury of precaution, of kicking the can down the road, is no longer a viable management option.” He cites as an example the Baltic harbor porpoise. The International Union for Conservation of Nature classifies this species, one of 16 distinct populations of harbor porpoises in the North Atlantic region, as Critically Endangered. Fewer than 100 fertile females are estimated to be alive.

“Scientists have monitored the decline of this animal over decades without any management intervention,” he adds. “The European Commission is now considering emergency management measures to rescue it from extinction, including use of pingers. I think the lesson here is don’t wait until things become critical.”

Lighting The Way

COURTESY OCEAN DISCOVERY INSTITUTEIllumination on fishing nets reduced bycatch of green sea turtles between 40 and 60% in Baja California fisheries.

On the other side of the world, researchers have been testing a different method of reducing bycatch, this one for sea turtles.

Bycatch in gill nets represents a major threat to sea turtles in Mexico’s Gulf of California, says Joel Barkan, research and restoration manager at the Ocean Discovery Institute. The institute provides science opportunities to young people from underserved urban communities, pairing them with mentors and providing ocean science programs at no cost. In addition to classroom and lab activities, students get the chance to participate in actual scientific research in San Diego and Mexico.

Researchers worked with Mexico’s National Commission for Protected Natural Areas in Baja California and fishers in villages on the Gulf of California and Pacific coasts to gauge the effectiveness of attaching LED lights to fishing nets in order to reduce sea turtle bycatch. The study showed that illumination on fishing nets reduced bycatch of green sea turtles between 40 and 60 percent, without changing catch of the target species—an important point for those who make their living fishing.

“Fishermen want to avoid catching sea turtles, as they have to take time to untangle them and the reptiles could damage their nets,” Barkan says. “They also don’t want to catch them because they care about conservation of turtles.”

According to a team from the University of Exeter in the U.K., Peruvian conservation nonprofit ProDelphinus and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, lights on nets reduced green sea turtle bycatch 65 to 80 percent for vessels operating out of three ports in Peru, again without changing target catch. In tests funded by the World Wildlife Fund in Indonesia, ultraviolet lights reduced sea turtle bycatch by up to 60 percent and actually boosted target catch by 20 percent.

Turtles can see certain light wavelengths that many fish species can’t, so using the right type of light helps turtles see and avoid the nets without tipping off the fish. Various studies tested green, orange and ultraviolet lights and found that each reduced sea turtle bycatch at a similar rate without affecting catch of the target species. (Placing shark silhouettes along a gill net significantly reduced bycatch of green turtles, but also decreased target catch.)

“The luxury of precaution, of kicking the can down the road, is no longer a viable management option.” - Rob Enever, Fishtek Marine

In each of these studies, lights also reduced bycatch of other species, such as seabirds, sharks and cetaceans. In Peru, for example, illuminated nets reduced bycatch of small cetaceans by 70 percent and that of seabirds by 84 percent.

“On the boat, everything happens fast,” says Antonio Figueroa, who assisted with the Mexico bycatch study as a student through the Ocean Discovery Institute. “The fishermen are very willing to participate, not only for conservation but because when they catch a turtle, it backs them up in bringing in the fish. They don’t want these setbacks. They’re very open and willing to work with researchers on innovative ways to reduce bycatch.”

Scientists are working on making the devices as affordable and easy to use as possible, including using solar power rather than batteries. “If the lights are not put on properly, they could damage the net or other gear,” says Figueroa. “Another problem could be taking the lights off the net to replace the battery. Solar lights would reduce that need, making the lights more permanent and nets faster to get out.”

GERALD NOWAKUsing certain light wavelengths helps turtles see and avoid the nets without tipping off the fish.

Solar-powered lights offer other benefits, says Jesse Senko, an assistant research professor at Arizona State University. Batteries only last a few weeks, and a typical fishing net might need 200 of them. Fishers likely would struggle to afford that many batteries, which also would generate a lot of waste. Opening the lights to replace batteries can eventually ruin the waterproof seal.

To refine the light design, ASU’s Solar Power Lab partnered with Grupo Tortuguero, a nonprofit network working with communities in Baja California to protect sea turtles, and local fishers. A few minutes into the first meeting, Senko says, the fishermen suggested putting lights into the buoys that they use to keep their nets afloat. The lab jumped on that idea.

“We created a lighted buoy that is positively buoyant and integrates into existing fishing gear,” Senko says. “We’re not adding something else that they have to worry about.” Flexible solar panels wrap around the cylindrical buoys, meaning part of the panel is always out of the water and recharging the battery inside. The designers also determined that a blinking rather than steady light meant the lights could remain on for an entire week with only about 30 minutes of sunlight to recharge, which can be accomplished when nets are brought into the boats or dried on the docks. In tests, the blinking lights reduced sea turtle bycatch 65 to 75 percent. Now researchers are tinkering with the flash rate, how the light hits the net and other tweaks to try to improve that figure.

“We also found no significant decreases in catch of the target fish. Fishermen don’t have to worry about the devices at all; they just fish the way they’ve always fished,” Senko says. “It doesn’t add an extra layer of work; they don’t have to clip lights on and off or change the battery. They just put it on like a regular buoy.”

“They use these nets for a reason—because they catch a lot of fish,” he adds. “We’re working with the fishermen, not saying they’re the bad guys and we’re going to shut them down. Fishing is culturally important here. They love to fish.”

The team is now searching for a manufacturer that can mass produce the lighted buoys. Meanwhile, other research underway looks at whether sound repels sea turtles the way it does porpoises, or if combining lights and sound can reduce bycatch even further.

Proven Methods

Bycatch is by no means a new threat to ocean life. Scientists and governing bodies have been proposing solutions in the form of research and regulations for decades. Longline fishing, which uses hundreds of individual lines with baited hooks hanging from a main line that stretches long distances across the sea surface, is another method that contributes heavily to bycatch of threatened species. Longlines catch swordfish, tuna and other commercially valuable fish that swim in the upper depths of the open sea. But longlines also catch sea turtles (especially leatherbacks and loggerheads), birds and other marine life, often causing them to drown.

In 2004, the United States began regulating the type of bait and hooks used in Pacific and Atlantic longline fisheries. Researchers from NOAA, Oregon State University and the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation Oceans Program recently analyzed more than 20 years of bycatch data from before and after these regulations were imposed. Their study showed that changing from traditional J hooks to circle hooks and using fish as bait instead of squid significantly reduces bycatch of sea turtles. Even just changing the bait alone can make a significant difference.

“Fishermen don't have to worry about the (LED) devices at all; they just fish the way they've always fished. It doesn't add an extra layer of work." - Jesse Senko, Assistant Research Professor, Arizona State University

Hundreds of thousands of seabirds are killed each year by global fisheries, including longline operations, but brightly colored, flapping ribbons called streamers can reduce longlining bird bycatch. In the 1990s, entangled seabirds became a major problem for the Alaskan longline groundfish fishery, and regulations required adding streamers to the gear beginning in 2002. Since then, the number of albatross deaths has decreased by 89 percent, and that of other seabirds by 77 percent, according to a report by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch.

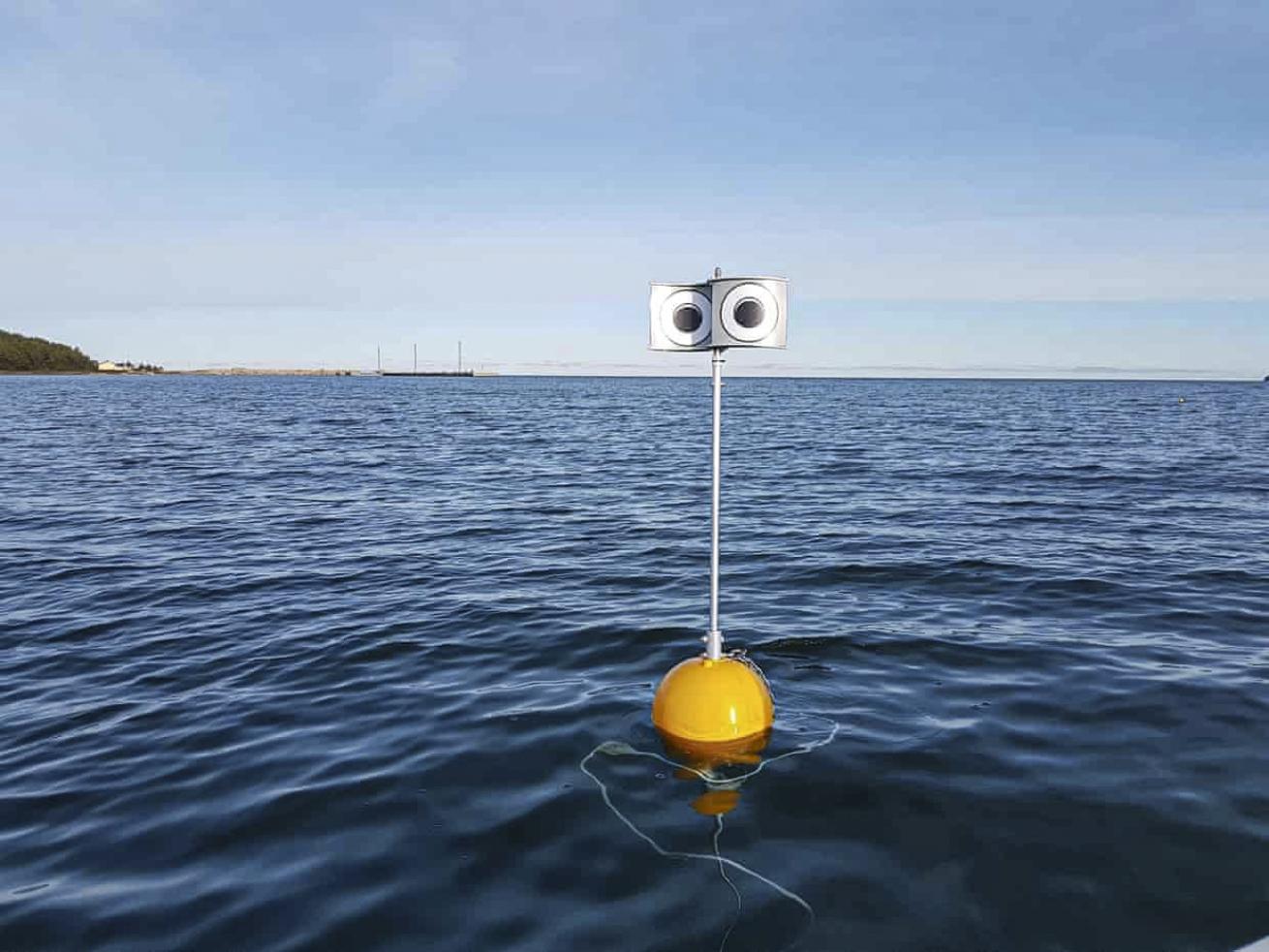

Gill nets alone kill an estimated 400,000 seabirds each year. A recent study led by the BirdLife International Marine Programme in the U.K. tested a floating device with large “eyes” to keep birds away from areas with fishing nets. These marine scarecrows rotate in the wind, and a small pair of eyes on one side and larger pair on the other create a looming effect, which is known to trigger a collision-risk signal in birds. During a 62-day test, the number of long-tailed ducks within a radius of about 54 yards of the device dropped by up to 25 percent. The unpredictability of the spinning should prevent birds from becoming used to the devices, researchers say.

A number of science-based management rules and regulations in U.S. fisheries help ensure responsible operations, including reducing bycatch. But the majority of seafood eaten in the United States is imported. Regulations that require imported fish products to meet the same standards as domestic ones, and demand from customers (see “Buy Seafood, Not Bycatch” below), could encourage operations in other countries to try harder to reduce bycatch and protect threatened species. After all, we have proven ways to accomplish that, many of them relatively simple, inexpensive and without adverse effects on the livelihood of fishers. That’s good news for people who fish for a living, those who eat fish, and divers who enjoy watching marine life thrive in the ocean.

Science-Based Solutions

A few tools are already making a measurable impact in the field.

LED Lighting

FISHTEK MARINELED Lighting

Researchers with the Ocean Discovery Institute found that attaching LEDs like these to gill nets deployed in the waters of Baja California, Mexico, reduced green sea turtle bycatch between 40 and 60 percent, a result replicated in several other fisheries around the globe. This solution also does not adversely affect fishers’ intended catch.

Banana Pingers

FISHTEK MARINEBanana Pingers

These relatively inexpensive acoustic devices made by U.K.-based Fishtek Marine attach to fishing nets and emit a high-pitched noise when submerged, effectively warding off dolphins and porpoises before they are caught in the nets and drowned. In two U.S. fishery studies, pingers reduced porpoise bycatch by 70 percent.

Looming-Eyes Buoy

FISHTEK MARINELooming Eyes

Likened to marine scarecrows, these simple devices float on the surface near gill nets and rotate in the wind, scaring away seabirds that might otherwise become ensnared underwater. The different sizes of the “eyes” create a looming effect that tells birds to steer clear.

Circle Hooks

Using circle hooks instead of traditional J hooks has proven effective in significantly reducing bycatch, according to 20 years of data amassed since the United States began regulating the type of bait and hooks used in Pacific and Atlantic longline fisheries.

Streamers

Brightly colored flapping ribbons attached to longlines have reduced albatross deaths by 89 percent and those of other seabirds by 77 percent in the Alaskan longline groundfish fishery since regulations were put in place in 2002.

Buy Seafood, Not Bycatch

CLAUDIO CONTRERASWild-Caught Seafood

You can help reduce bycatch by making the right choices when buying seafood.

The Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch program produces downloadable guides identifying seafood caught in a way that promotes the long-term well-being of wildlife and the environment. Its criteria for wild-caught seafood include recommending populations that are not overfished and fisheries that use gear with minimal impact—which includes reducing bycatch. Users can search the guides online by type of seafood, harvest method, and country or region, or they can download or print the guides. Choose products rated “Best Choice.”

Look for fish labeled as pole-and-line caught too. This method catches fish one at a time, which allows for the release of unwanted animals.

Ask restaurants and shops whether they sell sustainable seafood, which encourages them to consider those options. Thank those that do. Encourage those that don’t to check out Seafood Watch. “We have found that businesses really respond to consumer voices,” says Seafood Watch’s Ryan Bigelow.

Seek out local, sustainable seafood or at least seafood harvested in the United States. Remember that foreign imports are cheaper because those fisheries seldom follow the same rules as those in this country.

Seafood fraud—mislabeling or substituting species—often covers up illegal practices. Conservation nonprofit Oceana has an ongoing campaign for policies to require consistent names for seafood, as well as traceability from boat to plate, which you can learn more about and support at oceana.org.