Ice Diving and Photography with Narwhals in the High Arctic

Daniel BotelhoUnderwater narwhal in the High Arctic

STALKING THE UNICORN

Below the ice in the High Arctic, the mythical narwhal presents the ultimate challenge for underwater wildlife photographers. But capturing the shot was the experience of a lifetime.

Daniel BotelhoSnowmobile crosses the ice in Arctic Bay, Canada

THE JOURNEY

The journey started in summer at remote Arctic Bay, Baffin Island, Canada. The used snowmobiles to make the two-day trip to the floe edge, the frontier between ice and the open seas. Towing everything they needed on sleds — scuba tanks, compressors and weight belts, not to mention tents, camping tools, water, food, fuel and power generators — they were traveling heavy.

Daniel BotelhoOrange Tent on Ice at a Campsite in the High Arctic

HOME AWAY FROM HOME

Divers had to complete a two-day trek before getting to the beluga whales. They slept in a tent on top of frozen seas with external temperatures around minus 4 degrees F. The diving would then take place in 28-degree waters.

Daniel BotelhoNarwhals and calf underwater in the High Arctic

PLAYFUL NARWHALS

Narwhals, including a calf, playfully encircled the author after he waited hours for them to arrive.

Daniel BotelhoScuba diver underwater below thick ice in the High Arctic

BENEATH THE ICE

Overhead ice and the possibility of equipment failure make the High Arctic highly dangerous diving.

Daniel BotelhoDiver takes selfie underwater with narwhal

SCUBA SELFIE

The author takes a selfie with a narwhal that became so comfortable, she actually touched him (he calls her Martha).

Daniel BotelhoScuba Diver Beneath the Ice in the High Arctic

THE AUTHOR BELOW THE ICE

"I'm fascinated by icebergs, and the fact that I can showcase the entire piece of ice using the over/under photo technique, from the smallest tip to the huge underwater portion. Diving under the ice is an awesome experience — the environment is so uniform that a diver can lose himself and run out of air before finding his way back, so a rope tether is mandatory, as well as a backup tank and regulator to guard against freezing from accidental free-flow."

STALKING THE UNICORN

The clouds were dark and it was snowing hard, but my crew decided to head for the floe edge immediately to check for any narwhal activity. Conditions were terrible, but we needed to see what was happening.

When I first learned that my next assignment would be shooting narwhal whales in the High Arctic, I worried. Sleeping in a tent on top of frozen seas with external temperatures around minus 4 degrees F and diving in 28-degree waters were the least of my concerns. Narwhals are very shy and very hard to interact with, so even if we managed to live on the ice and dive in frozen waters, I would still be dependent on the will of the whales.

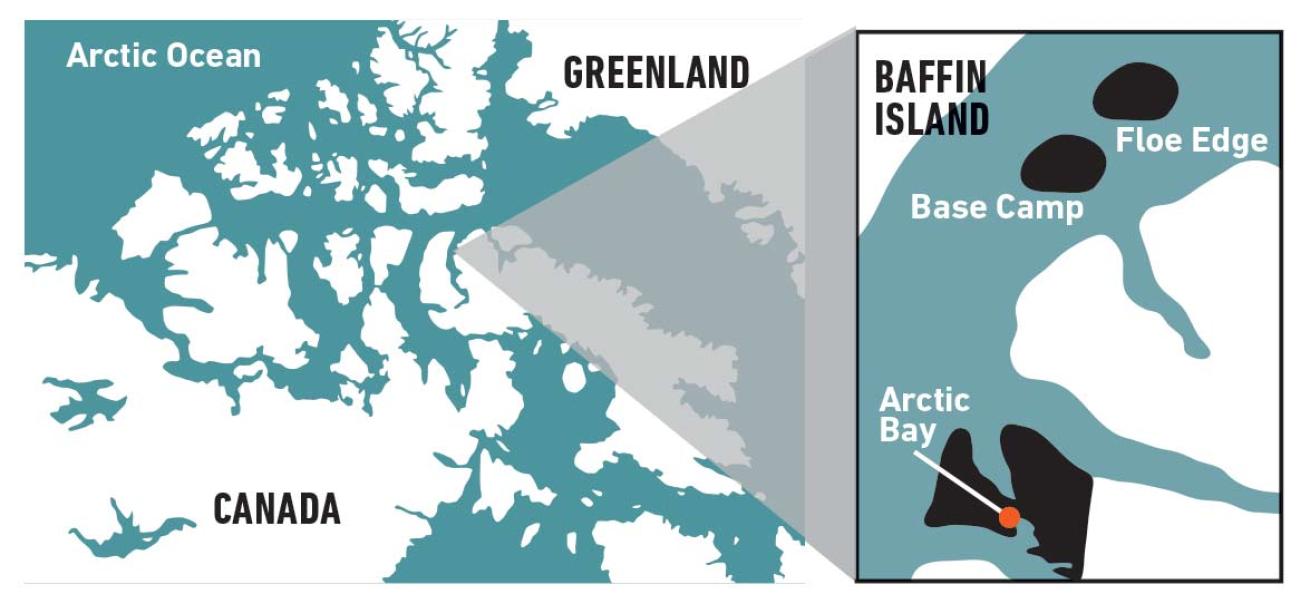

My journey started in summer at remote Arctic Bay, Baffin Island, Canada. My crew and I used snowmobiles to make the two-day trip to the floe edge, the frontier between ice and the open seas.

My team was made up of expert Canadian guides and Inuits, the local people who are owners of this land. Their expertise with ice and the animals is crucial to anyone wishing to pursue such an adventure. Towing everything we needed on sleds — scuba tanks, compressors and weight belts, not to mention tents, camping tools, water, food, fuel and power generators — we were traveling heavy.

At last we arrived at the spot chosen for base camp. Pieces of ice fields can break off easily and drift away into the sea, so we needed to camp some miles away from the floe edge where the ice was thick, necessitating an hourlong snowmobile ride to the edge and back each day.

I didn’t sleep the entire first night. Anxiety, fear of not being able to complete the assignment, and the so-called midnight sun — in summer, it never gets dark in the High Arctic — together with the sound of strong winds strafing my tent made sleep impossible.

This would be our first trip to the floe edge, and I really didn’t know what to expect. We arrived at the ice border, but to my despair there was crushed ice between the solid, frozen sea and open ocean. Crushed ice happens when an ice sheet drifts away from the main ice base; after a while, currents and winds bring the ice sheet back, slamming it into the main base. The drifting ice sheet breaks in many places, creating an unstable mass. Crushed ice would be our biggest enemy because it kept us away from the open seas.

Daniel BotelhoDaniel Botelho in the High Arctic

THE AUTHOR

Author Daniel Botelho stands in the snow.

A CUP HALF-FULL

Several days passed. We found a few holes in the middle of the frozen sea — not appropriate for narwhals but splendid for shooting icebergs.

I’m fascinated by icebergs, and the fact that I can showcase the entire piece of ice using the over/under photo technique, from the smallest tip to the huge underwater portion. If narwhals aren’t possible, I thought, at least I’ll have something to fill my memory cards.

Those early days at the High Arctic were beautiful, with very good weather. Diving under the ice is an awesome experience — the environment is so uniform that a diver can lose himself and run out of air before finding his way back, so a rope tether is mandatory, as well as a backup tank and regulator to guard against freezing from accidental free-flow.

The beautiful sunny days came and went, and still no narwhals. A huge storm was approaching, so we set out early for the floe edge, but it was almost as though blocks of snow were falling from the sky, and we aborted the mission, heading back to base camp. In the afternoon, some team members came to tell me: “Daniel, the snow is weaker now, and we can try getting to the floe edge. But we just had some fresh info from some Inuits that conditions at the edge are pretty much the same, with crushed ice.”

I looked to the dark clouds, a haunted sky with light awful for photos, the worst weather we had faced so far. And I thought to myself: “Today is narwhal day!” Despite the discouraging info and terrible weather, I took my gear and my snowmobile, and we left base camp.

We were still some miles from open sea when the Inuits stopped me, saying: “Daniel, take a look with the binoculars. A crack just opened, and we have open seas ahead of us. There is some action happening — we can see narwhals.”

In one second my heart sped like a race car, and my hands were shaking. I couldn’t miss this opportunity or I would never forgive myself.

Still far from the edge, I stopped the snowmobile and put on my drysuit. Continuing slowly, I arrived at the floe edge. Looking at the narwhals, I was drowning in adrenaline. The Inuits said to wait until they signaled the right time to get in the water; every second seemed like an eternity.

MYSTICAL MOMENT

As soon as I got clearance, I softly slipped from the ice to the sea, trying to be as stealthy as I could. Exhaust bubbles can scare narwhals away, so I was using only snorkel.

When I looked into the water, I could see nothing but black. I decided to swim farther out along the water channel, between the broken piece of drifting ice sheet and the frozen sea where I left my crew watching.

I reached the middle of the channel; I could see narwhals coming from a distance, but they were diving deep every time they got close to me.

As a wildlife photographer, I understand how important it is when dealing with shy animals to spend as much time as I can winning their trust. After two hours in 28-degree water, I finally saw my first close narwhal — still very deep and, because of thermoclines, distorted in appearance, which is no good for photos.

Currents were taking me close to the drifting ice sheet, but also very far from my crew and the safety of solid ice. I was focused on the animal interaction, but I started to think: “OK, I am really on my own now. If something happens to me right now, I am done; nobody can help me here.” Looking back, my crew appeared like tiny ants, and I knew I would have a long swim to safety.

Suddenly, all the pain I was feeling from the cold water and the huge effort started to make sense: A group of narwhals came close. I almost couldn’t believe what I was seeing: the mythic narwhal, unicorn of the seas. I was overwhelmed with a blast of sensations — happiness, excitement and determination not to make any mistakes with photography or the interaction.

The animals came to me many times. Males — the ones with the tusk, which is in fact a long tooth — are aloof and shy, but after three hours in the water together, they were frisky and curious about me. I was eager to spend as much time as I could — even though my mask had started leaking and I had some frostbite on my face, I was having the time of my life.

Then I heard a gunshot.

I looked to my crew, tiny in the distance, and could see a big flag waving from left to right. I wasn’t sure what was happening, but the gunshot and flag could not be good — my life could be in danger. Suddenly fear and stress took over. I had at least a 40-minute swim against the current, and I was worried.

Uncomfortable and not feeling well, I suddenly realized narwhals were all around me, swimming together, escorting me! They clearly felt my fear and moved to protect me.

After almost four hours in the water, now getting closer and closer to my crew, I felt something bumping my right leg. I looked behind and saw a female narwhal — she was playing with me, close enough to touch me many times, seemingly asking: “Where are you going? Why such a hurry?” That was a surreal event; I felt so blessed to achieve that confidence level and interaction with such a magnificent creature.

When I got close enough to the solid ice to have a conversation with my crew, I asked what was going on and if I should get out of the water. I really didn’t want to leave, I told my team: Look what is happening!

The narwhals were circling me and playing with me; my entire crew’s eyes were wide with disbelief.

Then they explained the problem. The Inuits were concerned about noises they were hearing that could represent small cracks in the ice that might lead the entire sheet we were on to break and drift. I urgently needed to get out of the water so we could go back to base camp. Once on stable ice, I could not resist falling to my knees, crying and kissing the ground, thrilled with such an experience.

Our mission was accomplished — after a month diving with icebergs, we finally had found the mythical narwhal whale, and it was time to leave the land of the midnight sun. But the adventure was not yet over.

EPILOGUE

Arriving at Arctic Bay after another two-day trip from the floe edge, something unusual happened. I started to be invited by local people to visit their homes — they all wanted to hear the story of the man befriended by narwhals. For Inuits, the tales they had heard from our team members had a deep, spiritual meaning.

I thought the story was over at that point. But two days after I arrived home in Rio de Janeiro, I was watching the news on TV and saw that a crew had gotten stuck on a drifting sheet of ice. It was my own crew, half of whom had stayed at base camp in order to pack and organize the logistics of departure. They awoke one morning and found themselves 8 miles away from their original point — a big crack had opened unexpectedly, and now the place we called home for a month was literally out to sea, and my friends were in dire need of rescue. Words cannot express the feelings — it took me a while to put myself together after this thunderous news, knowing that all was gone. After four days, all of my crew members were safely rescued by a Canadian Coast Guard helicopter, a unique end to a unique journey, and disturbing evidence that climate change is causing critical and unusual melting. It was a reminder that we must all do what we can to protect this wild and beautiful place, home to such magnificent animals, so that we might keep it untouched as our legacy, and the heritage of future generations.

Monica AlbertaThis map of Baffin Island shows where the High Arctic is located in relation to Greenland.

TRAVEL GUIDE FOR DIVING THE HIGH ARCTIC

When to Go: The best season to do an expedition like this is the beginning of summer.

Dive Conditions: The water temp is around 28 degrees F; visibility might vary depending on the amount of melted fresh water mixed with salt water. A drysuit is mandatory; a full-face mask is helpful for warmth. All dives are tethered for safety.

Operator: Arctic Kingdom has experts who can provide the best experience for High Arctic expeditions.

Price Tag: A seven-night Narwhal and Polar Bear Safari for summer 2016 starts at $9,995, double occupancy.

WHAT IT TAKES TO DIVE THE HIGH ARCTIC

The most important requirement for such an expedition is to have a positive attitude about the cold. An adventurous spirit is crucial, and having the right clothes is mandatory — at least four layers. (Your tour operator can help with this.) It’s good to be familiar with drysuits and ice diving, as well as having excellent underwater navigation skills. You don’t need to be an Ironman athlete, but it is best to be fit and ready for long swims if you truly wish to get face to face with a narwhal.

Want more ice-diving photos? Go underwater in Russia's White Sea.

Daniel BotelhoDaniel Botelho used a Nikon D4 and Nikkor 16mm fisheye with a signature Subal ND4 housing he helped develop and Subal 10-inch dome port.

HOW TO SHOOT PHOTOS IN THE HIGH ARCTIC

Don't Use Strobes Cetaceans are very sensitive, and strobes will scare them away. Wildlife photography is about patience — remember you can never “steal” a shot; the animal needs to give you the shot. Being as quiet and stealthy as possible is very important in gaining the confidence of the animal.

Light It Right Light can be poor underwater, so high ISOs are very important; I used 1800 ISO for some narwhal photos because you need to have a minimum aperture size to keep a decent depth of field and a good shutter speed to freeze the action.

Embrace the Sun For icebergs and split-shots, never forget to have the sun behind you — use the best of natural light in fullness.

Go with the Flow In the High Arctic, the view doesn’t change much, so work with what the environment offers: light. In summer, light from the midnight sun can be beautiful when the weather permits. Lenses also add variety, from fisheyes to telephotos. A polarizer is helpful.