Bringing in the Bluefin Tuna

Bluefin tuna is one of the most valuable fish species in the world, the focus of a multibillion-dollar industry in the Mediterranean Sea. Harvesting bluefin was described by Pliny the Elder more than 2,000 years ago.

In more-recent times, religion and tradition played a strong role in capturing the bounty of the spring migration from the Atlantic into the warmer Mediterranean, where tuna spawn. The rais — Arabic for leader — supervised a complex system of nets called tonnara. Patron saints were exhorted to guide the feet. Those old ways of fishing now exist only as a tourist attraction. That highly selective process, with limited environmental impact, was followed by a much more invasive approach that relied on sophisticated instruments and even air support to locate the fish.

The unsurprising result was overfishing of bluefin tuna, considered endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Today, fishing of bluefin tuna is governed by the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT). Since 2008, bluefin fishing has been limited to one month per year, usually May 15 to June 15. Bluefin tuna are caught alive and sold to farms, where they are fattened on sardines before being killed and sold, mostly to Japan.

Divers play a role in today’s process. Once the tuna is netted, the catch must be quantified. Divers with video cameras enter the net “cage,” and make an estimate of the number and size of the fish. Once the fishermen and the ICCAT inspector agree that ICCAT quotas and restrictions are met, the fish are ready to be transferred to the farm company. When the farm’s tow boats arrive, the net cages are attached, and divers open a passage between. Divers film the bluefins’ passage — this video is often the only means of determining quantity, number and weight of fish transferred. Fishermen and farmers can spend hours watching and rewatching the video, arguing and trying to come up with a sum to close the sale.

According to ICCAT, the regulations are working. Last year it declined to increase catch limits — a change requested by many member countries because of bluefin tuna recovery in the Mediterranean. ICCAT determined instead to stick with present controls, which are largely respected, and expects that in a few years bluefin tuna might be completely out of danger.

Want to read more about the Mediterranean?

Mediterranean Expedition | Gozo Uncovered | Essential Europe

Antonio BusielloFishermen gather bluefin tuna into nets.

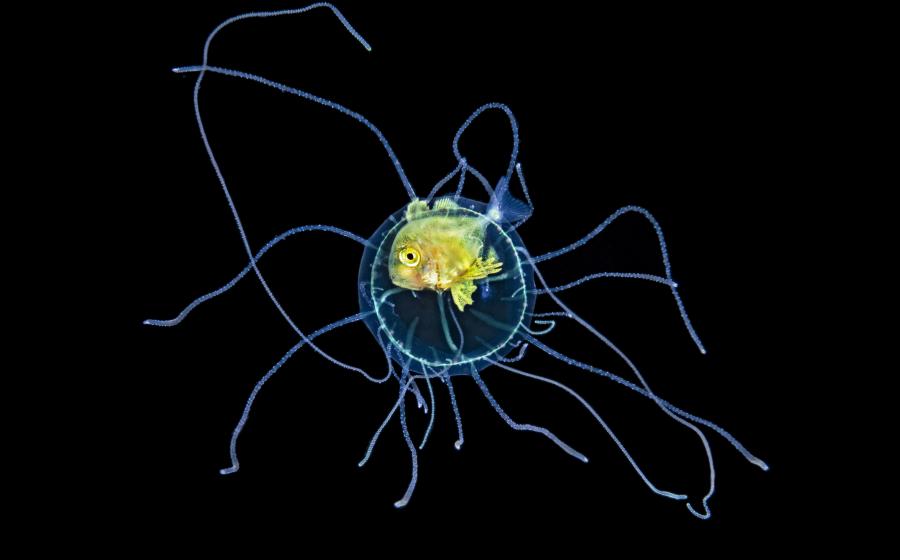

Antonio BusielloA diver opens a passage between fishing and farm nets.

Bluefin tuna is one of the most valuable fish species in the world, the focus of a multibillion-dollar industry in the Mediterranean Sea. Harvesting bluefin was described by Pliny the Elder more than 2,000 years ago.

In more-recent times, religion and tradition played a strong role in capturing the bounty of the spring migration from the Atlantic into the warmer Mediterranean, where tuna spawn. The rais — Arabic for leader — supervised a complex system of nets called tonnara. Patron saints were exhorted to guide the feet. Those old ways of fishing now exist only as a tourist attraction. That highly selective process, with limited environmental impact, was followed by a much more invasive approach that relied on sophisticated instruments and even air support to locate the fish.

The unsurprising result was overfishing of bluefin tuna, considered endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Today, fishing of bluefin tuna is governed by the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT). Since 2008, bluefin fishing has been limited to one month per year, usually May 15 to June 15. Bluefin tuna are caught alive and sold to farms, where they are fattened on sardines before being killed and sold, mostly to Japan.

Divers play a role in today’s process. Once the tuna is netted, the catch must be quantified. Divers with video cameras enter the net “cage,” and make an estimate of the number and size of the fish. Once the fishermen and the ICCAT inspector agree that ICCAT quotas and restrictions are met, the fish are ready to be transferred to the farm company. When the farm’s tow boats arrive, the net cages are attached, and divers open a passage between. Divers film the bluefins’ passage — this video is often the only means of determining quantity, number and weight of fish transferred. Fishermen and farmers can spend hours watching and rewatching the video, arguing and trying to come up with a sum to close the sale.

According to ICCAT, the regulations are working. Last year it declined to increase catch limits — a change requested by many member countries because of bluefin tuna recovery in the Mediterranean. ICCAT determined instead to stick with present controls, which are largely respected, and expects that in a few years bluefin tuna might be completely out of danger.

Want to read more about the Mediterranean?

Mediterranean Expedition | Gozo Uncovered | Essential Europe