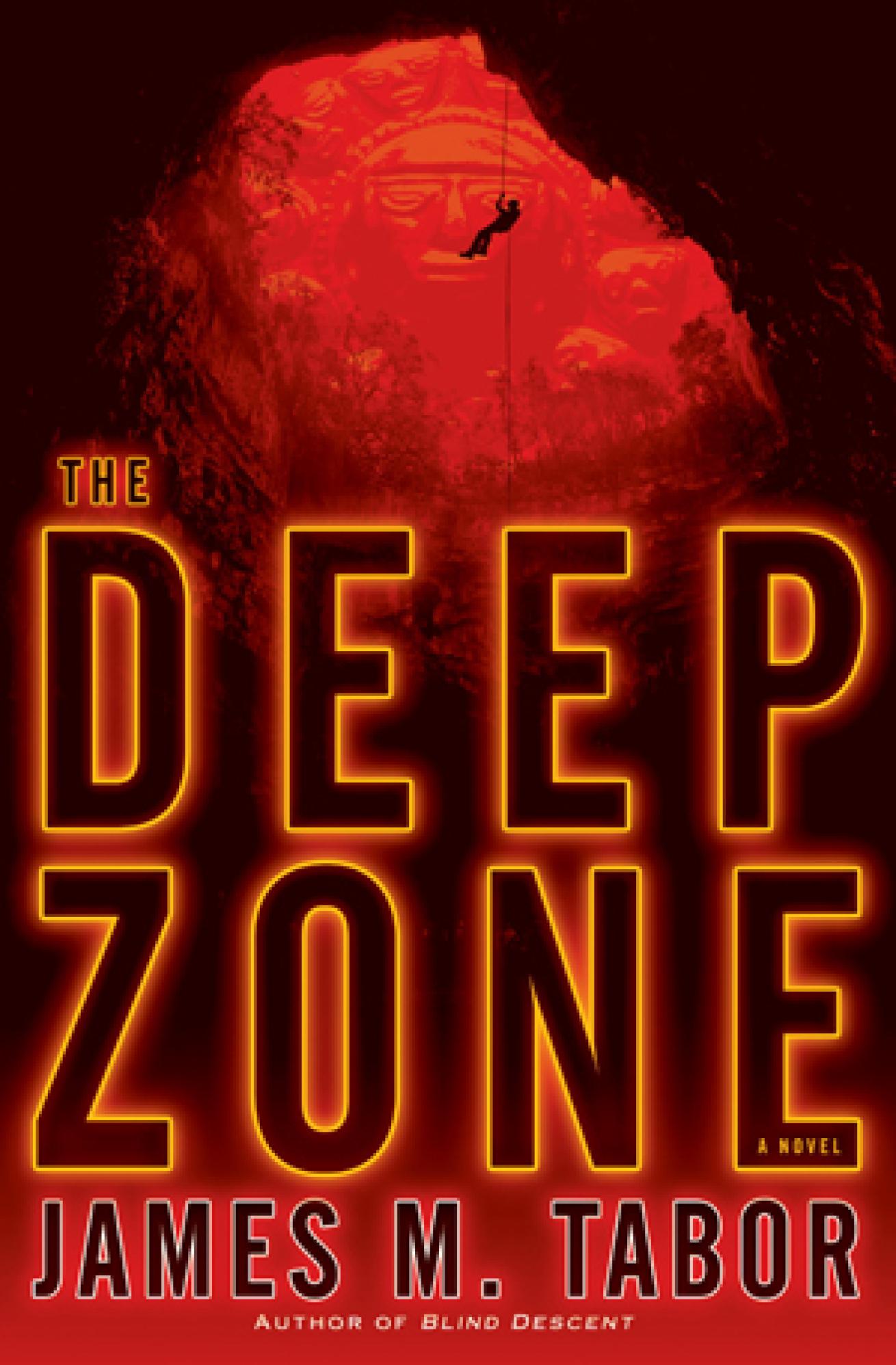

Book Review: The Deep Zone By James M. Tabor

The Deep Zone

Courtesy of James M. Tabor

What makes a good thriller? Story and pacing are important of course, and that’s enough for some people — witness the success of Clive Cussler novels. But for a discerning reader, even a great story can be sabotaged by wooden characters or unrealistic dialogue. The best thrillers are written by people with enough writing skill to convince the reader to suspend disbelief and “live” in the story. This is the kind of skill that James M. Tabor employs in his novel The Deep Zone.

You need look no further than his opening paragraph:

Some nights, when the winds of spring rise up out of Virginia, they peel fog from the Potomac and drape it over the branches of dead trees trapped in the river’s black mud banks. Streamers pull free and flow into the mews of Foggy Bottom and the cobblestoned alleys of Old Georgetown, float over the chockablock townhouses, and finally wrap pale, wet shrouds around war-fortune mansions.

That is poetic, and so much more evocative than simply stating “It was a foggy night.” Tabor uses his literary skill to fashion a plot that is as believable as it is chilling. A highly contagious and deadly new bacterium resistant to all known antibiotics is discovered in Afghanistan and is spread stateside before anyone realizes what is happening. In order to prevent a pandemic, an elite team must venture deep into a supercave called Cueva de Luz to retrieve “moonmilk,” a funguslike extremophile that can be used to create an antibiotic.

Enter Hallie Leland, who led a previous expedition that discovered the moonmilk. An experienced spelunker and cave diver, she is one of only two people ever to venture into Cueva de Luz and return alive. Now she must lead a team back into the cave and face sheer drops, flooded passages and lakes of acid to find and extract more of the extremophile.

To complicate matters, the cave is now in a region of southern Mexico controlled by narcotics smugglers. And there are influential and highly placed government pawns of a powerful pharmaceutical conglomerate who want Hallie to fail, and who will not hesitate to use murder to accomplish their ends.

A story this complex could easily become absurd in the hands of a less accomplished writer, but Tabor holds it all together and makes it believable. The only minor gripe I have with the book is that Tabor hands the narrative off to several minor characters in the heart of the book. At one point, there are six of these concurrent strands going, which distracts from the central action in the cave. But Tabor neatly brings all the strands together by the end, and his technique provides the reader with a good perspective on the breadth of the epidemic and the conspiracy.

The dust jacket of the book features quotes that compare Tabor’s style to that of the late Michael Crichton, and that’s a fair comparison. Like Crichton, Tabor blends science-fact and science-fiction in a creative and believable way. Also like Crichton, Tabor understands how greed and resentment can manifest itself in evil acts, in the same way that the vast, empty darkness of the cave can bring forth the darkness of the human heart.

Be aware that most of the action takes place on terra firma, although there is a brief cave diving episode that reinforces my conviction never to venture into one of those water-filled holes. But if you are looking for a literate thriller that doesn’t require you to turn off your brain for the duration of the book, give James M. Tabor’s The Deep Zone a try.

Courtesy of James M. Tabor

What makes a good thriller? Story and pacing are important of course, and that’s enough for some people — witness the success of Clive Cussler novels. But for a discerning reader, even a great story can be sabotaged by wooden characters or unrealistic dialogue. The best thrillers are written by people with enough writing skill to convince the reader to suspend disbelief and “live” in the story. This is the kind of skill that James M. Tabor employs in his novel The Deep Zone.

You need look no further than his opening paragraph:

Some nights, when the winds of spring rise up out of Virginia, they peel fog from the Potomac and drape it over the branches of dead trees trapped in the river’s black mud banks. Streamers pull free and flow into the mews of Foggy Bottom and the cobblestoned alleys of Old Georgetown, float over the chockablock townhouses, and finally wrap pale, wet shrouds around war-fortune mansions.

That is poetic, and so much more evocative than simply stating “It was a foggy night.” Tabor uses his literary skill to fashion a plot that is as believable as it is chilling. A highly contagious and deadly new bacterium resistant to all known antibiotics is discovered in Afghanistan and is spread stateside before anyone realizes what is happening. In order to prevent a pandemic, an elite team must venture deep into a supercave called Cueva de Luz to retrieve “moonmilk,” a funguslike extremophile that can be used to create an antibiotic.

Enter Hallie Leland, who led a previous expedition that discovered the moonmilk. An experienced spelunker and cave diver, she is one of only two people ever to venture into Cueva de Luz and return alive. Now she must lead a team back into the cave and face sheer drops, flooded passages and lakes of acid to find and extract more of the extremophile.

To complicate matters, the cave is now in a region of southern Mexico controlled by narcotics smugglers. And there are influential and highly placed government pawns of a powerful pharmaceutical conglomerate who want Hallie to fail, and who will not hesitate to use murder to accomplish their ends.

A story this complex could easily become absurd in the hands of a less accomplished writer, but Tabor holds it all together and makes it believable. The only minor gripe I have with the book is that Tabor hands the narrative off to several minor characters in the heart of the book. At one point, there are six of these concurrent strands going, which distracts from the central action in the cave. But Tabor neatly brings all the strands together by the end, and his technique provides the reader with a good perspective on the breadth of the epidemic and the conspiracy.

The dust jacket of the book features quotes that compare Tabor’s style to that of the late Michael Crichton, and that’s a fair comparison. Like Crichton, Tabor blends science-fact and science-fiction in a creative and believable way. Also like Crichton, Tabor understands how greed and resentment can manifest itself in evil acts, in the same way that the vast, empty darkness of the cave can bring forth the darkness of the human heart.

Be aware that most of the action takes place on terra firma, although there is a brief cave diving episode that reinforces my conviction never to venture into one of those water-filled holes. But if you are looking for a literate thriller that doesn’t require you to turn off your brain for the duration of the book, give James M. Tabor’s The Deep Zone a try.