Crossing the Line

By Travis Marshall

Photography by Ike Eisenberg

Watch Ocean Corp's Camp CDE video - shot on location by ShrimpTank Productions. |

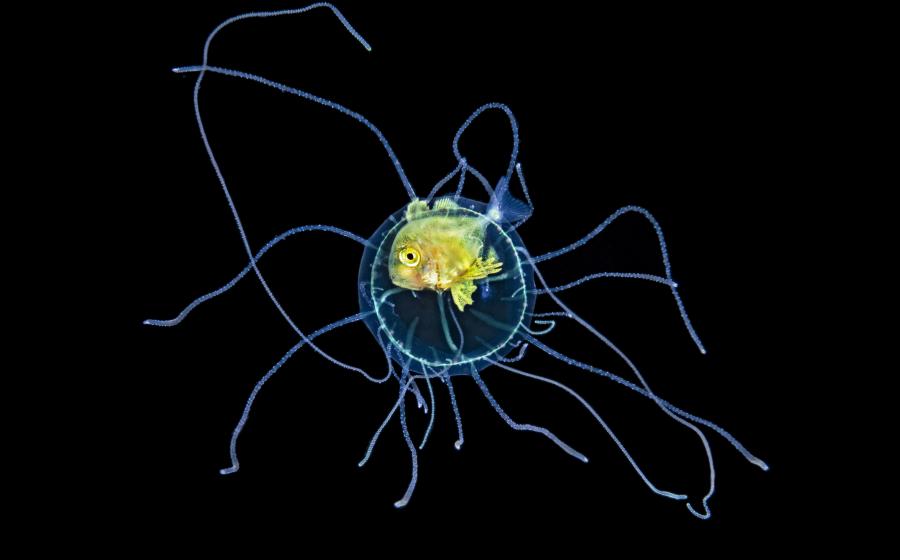

When you start thinking about diving for a living, you ultimately come to a fork in the road, as there are, simplistically speaking, two professional diving paths: the recreational side and the commercial one. A career in recreational diving is what most scuba divers fantasize about: tropical islands, white sand beaches and easy, shallow reefs where people fin around and marvel at the marine life. Follow the commercial diving path, and you enter a world of underwater roughneckery. Scuba tanks are replaced with diving hats and surface supplied air. And clinging to the struts of an oil platform, laying down a bead with a welding torch while fending off sharp-toothed creatures of the deep is just another day at the office.

Commercial diving is labor-intensive work that often requires divers spend months at sea or abroad in less than appealing destinations. But the money's good. A commercial diver fresh out of training can command close to 50 thou a year--not bad for someone without a college degree. And then there's the lifestyle. Like commercial fishermen, the stereotypical commercial diver loads up on women and booze between one fat paycheck and the next. "There's a reason so many of us marry strippers," jokes Mike Oden, career advisor for the Ocean Corporation, one of the leading commercial diving schools in the country. "When you're offshore for months at a time, you go a little crazy when you get back on land."

Ten years ago, as an 18-year-old fresh out of high school with a penchant for underwater adventure, I stood at that fork in the road, simultaneously doing my divemaster training and putting my feelers out to commercial diving schools like the Ocean Corporation--which actively seek out impressionable youths in search of adventure and a decent paycheck. Ultimately, I took the leisurely fork in the road and made my way as a dive instructor in some of the world's most enviable diving destinations. But one question always lingered in the back of my mind: What if?

And last August, the Ocean Corporation gave me, and 14 other average Joes from all walks of life, the opportunity to see how the other half lives. By signing up for the school's annual Commercial Diving Experience (CDE), I got an all-access pass to spend a weekend in a commercial diver's shoes--and diving hats--and answer that question for myself.

Nestled into the urban sprawl that is Houston, Texas, Ocean Corp has an unassuming appearance. From the front, its gate opens onto a small parking lot, and its façade gives every impression that it's just one more in the string of office buildings sharing its street. But when I crack the front door, a shelf of antiquated hats, spearguns and photographs greets me, and by the time I pop out the back end into the staging area, I'm transported to a more familiar world. Gear cages hold racks of drysuits patched with duct tape, banks of compressed air, scuba equipment and huge coils of hose. And a multilevel wooden platform behind the building is where the magic happens. The 4.2-acre campus has six diving tanks--three eight-foot tanks for underwater welding and cutting training, two 12-foot tanks and a 24-foot tank complete with a mock oil platform inside--not to mention a permanently installed medical decompression chamber, a portable decompression chamber and a 400-foot-rated lock-out diving bell.

Saturday morning, I join my fellow campmates, the student helpers and a handful of Ocean Corp instructors. The schedule says we'll start off with an equipment orientation and safety meeting before we "mobilize" at the 12-foot tank for some hat time, basically a meet and greet with the gear we'll use throughout the weekend. Two by two, we each strap on a harness with an emergency-bailout scuba tank, pull the neck dam--a metal ring with a drysuit-style neoprene seal--over our heads, and lock the hats down before leaping into the tank. The hats weigh 30 to 40 pounds each, so a weight belt isn't necessary, and topside, the weight puts a fair bit of strain on my neck. Underwater, I'm only slightly negative, albeit top heavy, and I hop my way around the tank like an astronaut on the moon, getting a feel for the flow adjustment valves and the less-than-clear communication system before running an out-of-air drill.

That afternoon is devoted to a mock work-dive scenario. I gear up on the edge of the 24-foot tank with my dive buddy, and when we're both ready to go, we make the leap and grab the down lines running to the bottom. With a loop of rope around one hand, I use the other to force the hat in and up on my face, which crams the hat's nose plug into my nostrils so I can equalize as I descend. Once I touch down on the bottom of the tank, my first task is making the switch from nitrox to mixed gas--a helium, nitrogen and oxygen mixture. "Crank your free flow, and count to 20," says the voice in my hat. "One, two...breathe...three, four...breathe," I respond. By about 14, my voice takes on the twangy, high-pitched character that lets my tenders know the mixed gas is flowing, and I turn to make my way hand-over-hand, low-gravity style, about 10 feet up the mock oil platform to the pipe flange we're here to assemble.

It's a relatively complex process requiring lift bag maneuvers and indirect communication with my work partner--we can't talk directly, but rather speak via the tenders on the surface--made even more challenging by the limited field of vision offered through the hat's faceplate. After about 15 minutes, we finish the task, put our tools back in the basket hanging from the surface and I return to my down line to switch over to nitrox and make my controlled ascent.

Because it's a simulated work dive, we feign a long, deep bottom time, and once we get out of the water, we have five minutes to strip down and climb into the decompression chamber before our blood starts to "boil." It's 100-plus degrees here in Houston, and a cramped metal tube baking in the summer sun doesn't look terribly inviting. But we climb in and make our way through the locks system into the main chamber where we're taken down to 50 feet and slowly brought back up to sea level over about 15 minutes. Amply decompressed, we scramble out of the chamber--it feels a bit like climbing out of pressure cooker--and go through a quick neurological evaluation before the instructors give us the all clear.

With the next day comes the highlight of the weekend, the moment many of us in the camp have been waiting for: Underwater cutting and welding. The cutting part uses a thermic rod--ignited by direct current and fueled by liquid oxygen--that burns at 6,500 degrees and cuts through damn near anything. The welding, in terms of the tools and basic concept, is similar to welding above water, but doing it underwater requires different techniques and an added safety concern--namely avoiding the electric current running through the water. Les Joiner, the former president of Ocean Corp, is on site today to take us through the two processes. "Like everything else in this industry, the safety rules for underwater welding and cutting are written in blood," Joiner says at the start of his safety briefing. "And all you have to do to avoid electric shock is not find yourself between the ground and the lead. If you get between where the plate's grounded and the end of this torch, you'll find out why they call it direct current." It's a simple rule. As long as we don't walk to the other side of the tank or point the end of the torch toward our bodies, there's no real risk of shock.

First, I hop into the cutting tank. A length of pipe stands upright on the cutting table. I pull the handle to let the oxygen flow, spark the torch and pierce the solid steel pipe with the tip of the rod. It slides through like the proverbial hot knife through butter. With a slight sawing motion, I attempt to cut a straight line across the pipe, but the result is a jagged mess. The welding process is equally simple to enact, but equally hard to do with any dexterity. Pulling the torch along what I hope is a straight line with one hand, while holding the bucket bouncing on my head with the other and trying to see anything through the billowing bubbles of smoke and the one- by three-inch welding lens duct taped to my mask, I gain immense appreciation for the focus and skill this school's students master on their way through the program. And when I get out of the welding tank and head for the showers, I realize my question has been answered.

Everything we've done this weekend is set up in a controlled environment so we can get a feel for the work these divers do every day without experiencing the true danger and desolation of a real working situation. But I get the picture. These divers are essentially living tools employed by the massive machines--usually the oil business--that they work for. They hang like bait on a hook in the open ocean, power tools in hand, doing work that's not only dangerous in and of itself, but also because of its depth and offshore location. The instructors who've been showing us the ropes are survivors. They beat the odds in a dangerous world and came out the other side to train the next generation, but the hardened looks on their faces and the gruff tones in their voices tell more about this life than any words could do. It's a job for the young. It's a job for the brave, maybe even the stupid. It's not the job for me. But for divers who have that same question gnawing in the backs of their heads, Ocean Corp is alone in the commercial diving world as a place that provides this camp to let people find that answer for themselves.

The Ocean Corporation is one of the world's leading commercial diving facilities. It's an accredited technical school that offers a variety of diver and nondiver training. The Commercial Diving Experience is offered annually at the beginning of August. Participants must be scuba-certified and 18 years or older; cost is $499 per person. For more information visit oceancorp.com or campcde.com.

By Travis Marshall

Photography by Ike Eisenberg

Watch Ocean Corp's Camp CDE video - shot on location by ShrimpTank Productions.|

When you start thinking about diving for a living, you ultimately come to a fork in the road, as there are, simplistically speaking, two professional diving paths: the recreational side and the commercial one. A career in recreational diving is what most scuba divers fantasize about: tropical islands, white sand beaches and easy, shallow reefs where people fin around and marvel at the marine life. Follow the commercial diving path, and you enter a world of underwater roughneckery. Scuba tanks are replaced with diving hats and surface supplied air. And clinging to the struts of an oil platform, laying down a bead with a welding torch while fending off sharp-toothed creatures of the deep is just another day at the office.

Commercial diving is labor-intensive work that often requires divers spend months at sea or abroad in less than appealing destinations. But the money's good. A commercial diver fresh out of training can command close to 50 thou a year--not bad for someone without a college degree. And then there's the lifestyle. Like commercial fishermen, the stereotypical commercial diver loads up on women and booze between one fat paycheck and the next. "There's a reason so many of us marry strippers," jokes Mike Oden, career advisor for the Ocean Corporation, one of the leading commercial diving schools in the country. "When you're offshore for months at a time, you go a little crazy when you get back on land."

Ten years ago, as an 18-year-old fresh out of high school with a penchant for underwater adventure, I stood at that fork in the road, simultaneously doing my divemaster training and putting my feelers out to commercial diving schools like the Ocean Corporation--which actively seek out impressionable youths in search of adventure and a decent paycheck. Ultimately, I took the leisurely fork in the road and made my way as a dive instructor in some of the world's most enviable diving destinations. But one question always lingered in the back of my mind: What if?

And last August, the Ocean Corporation gave me, and 14 other average Joes from all walks of life, the opportunity to see how the other half lives. By signing up for the school's annual Commercial Diving Experience (CDE), I got an all-access pass to spend a weekend in a commercial diver's shoes--and diving hats--and answer that question for myself.

Nestled into the urban sprawl that is Houston, Texas, Ocean Corp has an unassuming appearance. From the front, its gate opens onto a small parking lot, and its façade gives every impression that it's just one more in the string of office buildings sharing its street. But when I crack the front door, a shelf of antiquated hats, spearguns and photographs greets me, and by the time I pop out the back end into the staging area, I'm transported to a more familiar world. Gear cages hold racks of drysuits patched with duct tape, banks of compressed air, scuba equipment and huge coils of hose. And a multilevel wooden platform behind the building is where the magic happens. The 4.2-acre campus has six diving tanks--three eight-foot tanks for underwater welding and cutting training, two 12-foot tanks and a 24-foot tank complete with a mock oil platform inside--not to mention a permanently installed medical decompression chamber, a portable decompression chamber and a 400-foot-rated lock-out diving bell.

Saturday morning, I join my fellow campmates, the student helpers and a handful of Ocean Corp instructors. The schedule says we'll start off with an equipment orientation and safety meeting before we "mobilize" at the 12-foot tank for some hat time, basically a meet and greet with the gear we'll use throughout the weekend. Two by two, we each strap on a harness with an emergency-bailout scuba tank, pull the neck dam--a metal ring with a drysuit-style neoprene seal--over our heads, and lock the hats down before leaping into the tank. The hats weigh 30 to 40 pounds each, so a weight belt isn't necessary, and topside, the weight puts a fair bit of strain on my neck. Underwater, I'm only slightly negative, albeit top heavy, and I hop my way around the tank like an astronaut on the moon, getting a feel for the flow adjustment valves and the less-than-clear communication system before running an out-of-air drill.

That afternoon is devoted to a mock work-dive scenario. I gear up on the edge of the 24-foot tank with my dive buddy, and when we're both ready to go, we make the leap and grab the down lines running to the bottom. With a loop of rope around one hand, I use the other to force the hat in and up on my face, which crams the hat's nose plug into my nostrils so I can equalize as I descend. Once I touch down on the bottom of the tank, my first task is making the switch from nitrox to mixed gas--a helium, nitrogen and oxygen mixture. "Crank your free flow, and count to 20," says the voice in my hat. "One, two...breathe...three, four...breathe," I respond. By about 14, my voice takes on the twangy, high-pitched character that lets my tenders know the mixed gas is flowing, and I turn to make my way hand-over-hand, low-gravity style, about 10 feet up the mock oil platform to the pipe flange we're here to assemble.

It's a relatively complex process requiring lift bag maneuvers and indirect communication with my work partner--we can't talk directly, but rather speak via the tenders on the surface--made even more challenging by the limited field of vision offered through the hat's faceplate. After about 15 minutes, we finish the task, put our tools back in the basket hanging from the surface and I return to my down line to switch over to nitrox and make my controlled ascent.

Because it's a simulated work dive, we feign a long, deep bottom time, and once we get out of the water, we have five minutes to strip down and climb into the decompression chamber before our blood starts to "boil." It's 100-plus degrees here in Houston, and a cramped metal tube baking in the summer sun doesn't look terribly inviting. But we climb in and make our way through the locks system into the main chamber where we're taken down to 50 feet and slowly brought back up to sea level over about 15 minutes. Amply decompressed, we scramble out of the chamber--it feels a bit like climbing out of pressure cooker--and go through a quick neurological evaluation before the instructors give us the all clear.

With the next day comes the highlight of the weekend, the moment many of us in the camp have been waiting for: Underwater cutting and welding. The cutting part uses a thermic rod--ignited by direct current and fueled by liquid oxygen--that burns at 6,500 degrees and cuts through damn near anything. The welding, in terms of the tools and basic concept, is similar to welding above water, but doing it underwater requires different techniques and an added safety concern--namely avoiding the electric current running through the water. Les Joiner, the former president of Ocean Corp, is on site today to take us through the two processes. "Like everything else in this industry, the safety rules for underwater welding and cutting are written in blood," Joiner says at the start of his safety briefing. "And all you have to do to avoid electric shock is not find yourself between the ground and the lead. If you get between where the plate's grounded and the end of this torch, you'll find out why they call it direct current." It's a simple rule. As long as we don't walk to the other side of the tank or point the end of the torch toward our bodies, there's no real risk of shock.

First, I hop into the cutting tank. A length of pipe stands upright on the cutting table. I pull the handle to let the oxygen flow, spark the torch and pierce the solid steel pipe with the tip of the rod. It slides through like the proverbial hot knife through butter. With a slight sawing motion, I attempt to cut a straight line across the pipe, but the result is a jagged mess. The welding process is equally simple to enact, but equally hard to do with any dexterity. Pulling the torch along what I hope is a straight line with one hand, while holding the bucket bouncing on my head with the other and trying to see anything through the billowing bubbles of smoke and the one- by three-inch welding lens duct taped to my mask, I gain immense appreciation for the focus and skill this school's students master on their way through the program. And when I get out of the welding tank and head for the showers, I realize my question has been answered.

Everything we've done this weekend is set up in a controlled environment so we can get a feel for the work these divers do every day without experiencing the true danger and desolation of a real working situation. But I get the picture. These divers are essentially living tools employed by the massive machines--usually the oil business--that they work for. They hang like bait on a hook in the open ocean, power tools in hand, doing work that's not only dangerous in and of itself, but also because of its depth and offshore location. The instructors who've been showing us the ropes are survivors. They beat the odds in a dangerous world and came out the other side to train the next generation, but the hardened looks on their faces and the gruff tones in their voices tell more about this life than any words could do. It's a job for the young. It's a job for the brave, maybe even the stupid. It's not the job for me. But for divers who have that same question gnawing in the backs of their heads, Ocean Corp is alone in the commercial diving world as a place that provides this camp to let people find that answer for themselves.

The Ocean Corporation is one of the world's leading commercial diving facilities. It's an accredited technical school that offers a variety of diver and nondiver training. The Commercial Diving Experience is offered annually at the beginning of August. Participants must be scuba-certified and 18 years or older; cost is $499 per person. For more information visit oceancorp.com or campcde.com.