Dive Training: 23 Advanced Certifications

What's the best course to take after basic open-water certification?

For most divers, it's the advanced open-water course. This course gives you three things:

-

Diving experience with supervision. Still a bit nervous? Here is the chance to get more diving under your belt with the security of an instructor close by. More diving will sharpen your skills and reveal where you need more work. Though a complete review of basic open-water skills is not part of the course, a good instructor will notice if you're having problems and help.

-

An introduction to safety skills for advanced diving. Though courses vary, a good advanced open-water course will introduce you to many of the safety skills you need for typical recreational diving: deep diving, night or low-vis diving, underwater navigation, boat diving, drift diving, multi-level diving and more.

-

A chance to sample new underwater activities. Most advanced open-water courses include "electives." These are dives chosen by you and your instructor from the list of popular specialty courses. They give you the chance to try out, for example, underwater photography, underwater video, fish identification and biology, hunting and collecting, underwater archeology and wreck diving. Typically, if you go on to take a full specialty course, your advanced open-water dive will count toward the course requirements.

Reality Check

Different instructors and agencies have different educational philosophies. Some emphasize academics and exam-taking. Others are "performance based," believing that if you can demonstrate a skill in the water, what you can demonstrate on paper is irrelevant.

Some compress the course into the minimum amount of time. Others take a slower pace. Some rely on home study. Others like the discipline of an instructor in a classroom.

Which is "best" depends on you and how you learn. Be honest with yourself. Years of high school and college have taught most of us to evade demanding teachers and seek out easy ones. But the easiest may not be the best. Remember that you may be staking your life on what you do--or don't--learn.

I have an open-water certification card. Can I take courses from any training agency?

Yes. Every training agency we talked to considers "alien" C-cards as valid as their own when it comes to qualifying for the advanced open-water course or for specialty courses.

While every training agency's basic open-water certification is pretty much the same, advanced classes can vary considerably. For example, advanced open-water is a course with most agencies, including an instructor, a curriculum and an examination. But at SSI, it's a rating. Complete a total of 24 dives, take any four specialty courses, and you're entitled to the advanced open-water card. SSI believes that it's diving experience that counts, so at SSI an advanced open-water card means more independent diving, less instruction.

Should I take advanced open-water right away or wait until I have more experience?

It depends on your diving opportunities right now. If you can dive frequently, under conditions similar to those of your certification course, with a competent, experienced buddy, and you feel comfortable doing it, it's probably better to make a dozen dives and solidify what you learned in basic open-water before going on to new skills.

But if the local diving is a little intimidating, you don't have a good regular buddy and you are feeling nervous about diving without supervision, an advanced open-water course allows you to extend your time in "training wheels." All advanced open-water programs are designed with brand-new divers in mind, so you won't be out of place.

What about all these specialty courses? Do I need to take them?

Except for courses that focus on diving skills, you can think of most specialty courses as electives, the courses you choose because you're interested.

The Big 5: The Most Important Specialties

These courses teach the skills almost every diver needs. That's why several of them are sampled in most advanced open-water courses.

Rescue. Also called "Stress and Rescue," the course helps you to recognize the signs of anxiety in you and your buddy and teaches you what to do about it. You learn about common diving accidents, how to prevent them and how to manage them. You learn and practice common rescue techniques. Almost all training agencies we contacted agreed that this is the single most important specialty class.

Navigation. The potential to get lost exists on your first post-certification dive (and maybe sooner). The course typically covers both compass use and "natural" navigation--how to read the current, the bottom contour and the pattern of shadows to keep track of your position.

Deep diving. Basic open-water certification usually stops at 60 feet. The next 70 feet introduce new issues of air management and nitrogen narcosis as well as risks of decompression sickness.

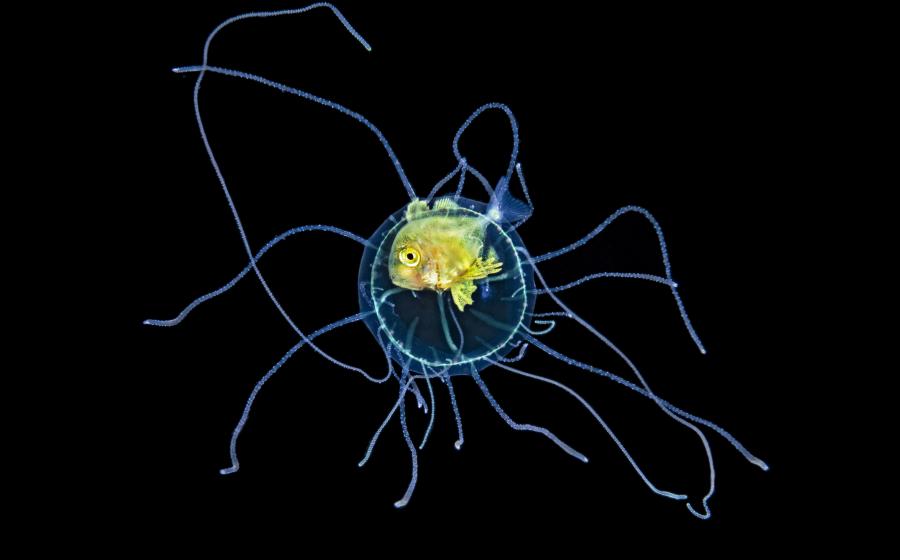

Night and low-visibility diving. New equipment is involved, and new problems of communication and disorientation arise. New creatures come out at night, too.

Boat diving. How to exit and reboard the boat safely. Understanding boat operation and terminology. Also, issues of dive boat customs and etiquette.

The Next 5: More Specialty Courses

These are the specialty courses that, in our opinion, give the most value. But hey, it's a free country.

Underwater naturalist. Also called Fish Identification, Underwater Ecology, etc. Anything that gives you a greater understanding of the marine environment makes diving more interesting.

Search and recovery. You may never need to recover, say, an outboard motor, but this course improves your navigation and buoyancy skills, and makes you more aware of what's around you.

Underwater photography. Photography sharpens your interest in what you see, improves your buoyancy skills and provides some of the fun of hunting without the bloodshed.

Diving in currents. This deals with currents, surge and wave action. Also drift diving and "live-boat" diving, situations you are likely to encounter sooner or later.

Wreck diving. Everybody loves wrecks. Even a non-penetration course teaches valuable stuff: how to orient yourself and navigate on a wreck, how to avoid silt and low-vis problems, etc.

Is there any difference between taking a specialty course at a local dive center or from a resort dive shop?

Taking a specialty course at a resort during a dive vacation is a popular way to blend education and fun. But will it be the same course? Maybe so, maybe no.

The pros and cons:

At a resort: The academic side will probably have a tropical flavor. Vacationers are often in no mood to study textbooks, and resorts do not stay in business by demanding homework. But with three to five dives scheduled every day, you will have more opportunity to practice new skills in the water. The course may cost less, because the dives are already paid for.

At home: A stand-alone course will probably have more academic content, more classroom time. If a CD-ROM or video is part of the course materials, it may be easier to use it at home. But the course will probably include less in-water time--typically, two to four dives total. And it may cost more because you'll be paying for the dives as well as the course.

Best of both? Some dive shops and agencies will allow you to take the academic part of the course at home, then do the diving part on your vacation--even if the resort pro is affiliated with a different agency.

Several dive shops in my hometown offer the same specialty courses. How do I pick one?

Ask for a few minutes of face-to-face time with the actual instructor. If the shop makes this difficult, go elsewhere. A meeting gives you a chance to size up whether your prospective teacher is articulate and sympathetic while you ask about:

Instructor's experience. It goes without saying that a teacher of night diving should have logged lots of night dives, that a teacher of underwater photography should have got his first camera more than six months ago. A less obvious question: how much experience teaching does the instructor have? Knowing a skill and being able to communicate it are different things.

Course objective. If you pass the course, should you feel comfortable performing the skill without supervision? Or is this only an introductory class?

Academic content. Will there be classroom lecture, home study or both? A written exam? About how many hours will be required?

Course materials. Is there a textbook you can keep? A video or CD-ROM?

Diving practice. How many dives are included? What specific skills will be practiced on the dives? If special equipment is required, will it be supplied or is rental or purchase extra?

Class size. Should be fewer than nine students. If more than three, will there be an assistant instructor also?

Certificate. Will you get a "diploma" or an additional C-card showing you have completed the course? This may be important if it is a prerequisite for courses you take subsequently.

References. Ask for names and addresses of recent graduates of the course. A reputable business that's proud of its work should be quick to offer references.

Tech Diving: Way Beyond the Basics

The popularity of nitrox, to say nothing of black BCs with lots of D-rings, testifies to growing interest in technical diving.

"Technical diving" generally refers to anything beyond the normal recreational limits: dives beyond 130 feet with scheduled decompression stops and different gas mixtures. It also includes penetration of caves and wrecks beyond the ambient light zone.

In response to this interest, the biggest training agencies are adding technical courses. NAUI has a tech diving program, and PADI is due to add one in 2001. Several other agencies specialize in technical training, like ANDI, IANTD and TDI. Subjects covered include advanced nitrox and tri-mix, use of rebreathers and decompression theory, as well as cave and wreck penetration.

But technical diving is emphatically not for everyone. The risks are considerably higher and the physical and mental demands are greater. You should be mature, physically fit and experienced. Moreover, you should examine your motives for wanting to do technical diving. Good motives, according to NAUI's Director of Technical Diving Tim O'Leary, might include wanting to dive the U.S.S. Monitor before it decomposes, or wanting to dive Truk. Bad motives? "Testosterone," says O'Leary.

Prerequisites generally include a minimum age (usually 18 or 21), 50, 100 or more logged dives, a level of physical fitness, and passing an interview designed to measure motivation, maturity and experience.

AOW At A Glance

What - 4-6 open water dives, little or no classroom instruction other than pre-dive and post-dive briefings.

Subjects - Sample specialties like night diving, boat diving, deep diving, wreck diving, search and rescue, underwater navigation. Some subjects, such as navigation, deep diving and night diving, may be required.

Time required - Can be as long as 32 hours, as short as one weekend.

Price - Varies from about $150-$250 for a stand-alone course, to $100 if added to a resort package.

Prerequisites - Open-water certification.

Are You "DIR"?

DIR is an acronym that scuba message board users have been hearing a lot about lately. It stands for "Doing It Right," a diving philosophy rooted in the discipline of cave diving.

The DIR approach to diving is as much about teamwork, physical fitness and pre-dive planning as equipment, but it is DIR's unusual gear configuration that generates the most comment. Here are the basics:

Backplate, harness and wings. Three pieces substitute for a BC. A steel or aluminum backplate, which holds the tank(s), is strapped to your body by a single piece of webbing, the harness, with one buckle. A crotch strap prevents it from riding up. A buoyancy compensating bladder is back-mounted, and can be replaced by various sizes for different buoyancy needs.

Long primary hose. Your primary regulator is on a hose that's five to seven feet long. That's because in a low-air emergency you will donate your primary reg to your buddy and switch to your backup, and the long hose gives you both room to maneuver. Your backup reg is held under your chin on a loop of surgical tubing. The long hose goes down your back on the right, comes to the front near your hip, then crosses your chest and goes over your left shoulder, behind and around your head and forward again to the reg. To donate it, you duck your chin and lift the loop of hose over your head.

Submersible pressure gauge. Instead of a traditional gauge console, DIR divers use a simple pressure gauge on a hose just long enough to reach your waist, where it hangs from your belt on the left.

If you don't need it, leave it. Minimalism leads to streamlining and less effort expended, less chance of confusion.

Who Uses DIR?

DIR was developed by the divers of the Woodville Karst Plain Project, an expedition to explore the far reaches of inter-connected fresh-water caves in North Florida. Reducing the huge risk of these dives requires close teamwork and careful attention to details.

DIR is also at the heart of training standards used by Global Underwater Explorers (GUE), an organization for divers interested in exploration, and a training agency. In addition to technical training, GUE also offers basic open-water certification that incorporates DIR.

Jarrod Jablonski, GUE president, co-founder of WKPP, and a chief proponent of DIR diving, believes that dive training has gone soft in trying to make it attractive to everyone. "Too many divers are not given enough training to feel comfortable in the water," he says. "So they stop diving."

GUE believes every diver, even the beginning recreational diver, is better off in the DIR "mindset" and equipment configuration. Does that mean equipping yourself like Edmund Hillary to take a walk in the park? "Affirmative!" say DIR true-believers. "Get with the program or get out of the water." Jablonski, however, is less dogmatic. "We have a niche," he says, "for the divers who want our kind of training."

What's the best course to take after basic open-water certification?

For most divers, it's the advanced open-water course. This course gives you three things:

Diving experience with supervision. Still a bit nervous? Here is the chance to get more diving under your belt with the security of an instructor close by. More diving will sharpen your skills and reveal where you need more work. Though a complete review of basic open-water skills is not part of the course, a good instructor will notice if you're having problems and help.

An introduction to safety skills for advanced diving. Though courses vary, a good advanced open-water course will introduce you to many of the safety skills you need for typical recreational diving: deep diving, night or low-vis diving, underwater navigation, boat diving, drift diving, multi-level diving and more.

A chance to sample new underwater activities. Most advanced open-water courses include "electives." These are dives chosen by you and your instructor from the list of popular specialty courses. They give you the chance to try out, for example, underwater photography, underwater video, fish identification and biology, hunting and collecting, underwater archeology and wreck diving. Typically, if you go on to take a full specialty course, your advanced open-water dive will count toward the course requirements.

Reality Check

Different instructors and agencies have different educational philosophies. Some emphasize academics and exam-taking. Others are "performance based," believing that if you can demonstrate a skill in the water, what you can demonstrate on paper is irrelevant.

Some compress the course into the minimum amount of time. Others take a slower pace. Some rely on home study. Others like the discipline of an instructor in a classroom.

Which is "best" depends on you and how you learn. Be honest with yourself. Years of high school and college have taught most of us to evade demanding teachers and seek out easy ones. But the easiest may not be the best. Remember that you may be staking your life on what you do--or don't--learn.

I have an open-water certification card. Can I take courses from any training agency?

Yes. Every training agency we talked to considers "alien" C-cards as valid as their own when it comes to qualifying for the advanced open-water course or for specialty courses.

While every training agency's basic open-water certification is pretty much the same, advanced classes can vary considerably. For example, advanced open-water is a course with most agencies, including an instructor, a curriculum and an examination. But at SSI, it's a rating. Complete a total of 24 dives, take any four specialty courses, and you're entitled to the advanced open-water card. SSI believes that it's diving experience that counts, so at SSI an advanced open-water card means more independent diving, less instruction.

Should I take advanced open-water right away or wait until I have more experience?

It depends on your diving opportunities right now. If you can dive frequently, under conditions similar to those of your certification course, with a competent, experienced buddy, and you feel comfortable doing it, it's probably better to make a dozen dives and solidify what you learned in basic open-water before going on to new skills.

But if the local diving is a little intimidating, you don't have a good regular buddy and you are feeling nervous about diving without supervision, an advanced open-water course allows you to extend your time in "training wheels." All advanced open-water programs are designed with brand-new divers in mind, so you won't be out of place.

What about all these specialty courses? Do I need to take them?

Except for courses that focus on diving skills, you can think of most specialty courses as electives, the courses you choose because you're interested.

The Big 5: The Most Important Specialties

These courses teach the skills almost every diver needs. That's why several of them are sampled in most advanced open-water courses.

Rescue. Also called "Stress and Rescue," the course helps you to recognize the signs of anxiety in you and your buddy and teaches you what to do about it. You learn about common diving accidents, how to prevent them and how to manage them. You learn and practice common rescue techniques. Almost all training agencies we contacted agreed that this is the single most important specialty class.

Navigation. The potential to get lost exists on your first post-certification dive (and maybe sooner). The course typically covers both compass use and "natural" navigation--how to read the current, the bottom contour and the pattern of shadows to keep track of your position.

Deep diving. Basic open-water certification usually stops at 60 feet. The next 70 feet introduce new issues of air management and nitrogen narcosis as well as risks of decompression sickness.

Night and low-visibility diving. New equipment is involved, and new problems of communication and disorientation arise. New creatures come out at night, too.

Boat diving. How to exit and reboard the boat safely. Understanding boat operation and terminology. Also, issues of dive boat customs and etiquette.

The Next 5: More Specialty Courses

These are the specialty courses that, in our opinion, give the most value. But hey, it's a free country.

Underwater naturalist. Also called Fish Identification, Underwater Ecology, etc. Anything that gives you a greater understanding of the marine environment makes diving more interesting.

Search and recovery. You may never need to recover, say, an outboard motor, but this course improves your navigation and buoyancy skills, and makes you more aware of what's around you.

Underwater photography. Photography sharpens your interest in what you see, improves your buoyancy skills and provides some of the fun of hunting without the bloodshed.

Diving in currents. This deals with currents, surge and wave action. Also drift diving and "live-boat" diving, situations you are likely to encounter sooner or later.

Wreck diving. Everybody loves wrecks. Even a non-penetration course teaches valuable stuff: how to orient yourself and navigate on a wreck, how to avoid silt and low-vis problems, etc.

Is there any difference between taking a specialty course at a local dive center or from a resort dive shop?

Taking a specialty course at a resort during a dive vacation is a popular way to blend education and fun. But will it be the same course? Maybe so, maybe no.

The pros and cons:

At a resort: The academic side will probably have a tropical flavor. Vacationers are often in no mood to study textbooks, and resorts do not stay in business by demanding homework. But with three to five dives scheduled every day, you will have more opportunity to practice new skills in the water. The course may cost less, because the dives are already paid for.

At home: A stand-alone course will probably have more academic content, more classroom time. If a CD-ROM or video is part of the course materials, it may be easier to use it at home. But the course will probably include less in-water time--typically, two to four dives total. And it may cost more because you'll be paying for the dives as well as the course.

Best of both? Some dive shops and agencies will allow you to take the academic part of the course at home, then do the diving part on your vacation--even if the resort pro is affiliated with a different agency.

Several dive shops in my hometown offer the same specialty courses. How do I pick one?

Ask for a few minutes of face-to-face time with the actual instructor. If the shop makes this difficult, go elsewhere. A meeting gives you a chance to size up whether your prospective teacher is articulate and sympathetic while you ask about:

Instructor's experience. It goes without saying that a teacher of night diving should have logged lots of night dives, that a teacher of underwater photography should have got his first camera more than six months ago. A less obvious question: how much experience teaching does the instructor have? Knowing a skill and being able to communicate it are different things.

Course objective. If you pass the course, should you feel comfortable performing the skill without supervision? Or is this only an introductory class?

Academic content. Will there be classroom lecture, home study or both? A written exam? About how many hours will be required?

Course materials. Is there a textbook you can keep? A video or CD-ROM?

Diving practice. How many dives are included? What specific skills will be practiced on the dives? If special equipment is required, will it be supplied or is rental or purchase extra?

Class size. Should be fewer than nine students. If more than three, will there be an assistant instructor also?

Certificate. Will you get a "diploma" or an additional C-card showing you have completed the course? This may be important if it is a prerequisite for courses you take subsequently.

References. Ask for names and addresses of recent graduates of the course. A reputable business that's proud of its work should be quick to offer references.

Tech Diving: Way Beyond the Basics

The popularity of nitrox, to say nothing of black BCs with lots of D-rings, testifies to growing interest in technical diving.

"Technical diving" generally refers to anything beyond the normal recreational limits: dives beyond 130 feet with scheduled decompression stops and different gas mixtures. It also includes penetration of caves and wrecks beyond the ambient light zone.

In response to this interest, the biggest training agencies are adding technical courses. NAUI has a tech diving program, and PADI is due to add one in 2001. Several other agencies specialize in technical training, like ANDI, IANTD and TDI. Subjects covered include advanced nitrox and tri-mix, use of rebreathers and decompression theory, as well as cave and wreck penetration.

But technical diving is emphatically not for everyone. The risks are considerably higher and the physical and mental demands are greater. You should be mature, physically fit and experienced. Moreover, you should examine your motives for wanting to do technical diving. Good motives, according to NAUI's Director of Technical Diving Tim O'Leary, might include wanting to dive the U.S.S. Monitor before it decomposes, or wanting to dive Truk. Bad motives? "Testosterone," says O'Leary.

Prerequisites generally include a minimum age (usually 18 or 21), 50, 100 or more logged dives, a level of physical fitness, and passing an interview designed to measure motivation, maturity and experience.

AOW At A Glance

What - 4-6 open water dives, little or no classroom instruction other than pre-dive and post-dive briefings.

Subjects - Sample specialties like night diving, boat diving, deep diving, wreck diving, search and rescue, underwater navigation. Some subjects, such as navigation, deep diving and night diving, may be required.

Time required - Can be as long as 32 hours, as short as one weekend.

Price - Varies from about $150-$250 for a stand-alone course, to $100 if added to a resort package.

Prerequisites - Open-water certification.

Are You "DIR"?

DIR is an acronym that scuba message board users have been hearing a lot about lately. It stands for "Doing It Right," a diving philosophy rooted in the discipline of cave diving.

The DIR approach to diving is as much about teamwork, physical fitness and pre-dive planning as equipment, but it is DIR's unusual gear configuration that generates the most comment. Here are the basics:

Backplate, harness and wings. Three pieces substitute for a BC. A steel or aluminum backplate, which holds the tank(s), is strapped to your body by a single piece of webbing, the harness, with one buckle. A crotch strap prevents it from riding up. A buoyancy compensating bladder is back-mounted, and can be replaced by various sizes for different buoyancy needs.

Long primary hose. Your primary regulator is on a hose that's five to seven feet long. That's because in a low-air emergency you will donate your primary reg to your buddy and switch to your backup, and the long hose gives you both room to maneuver. Your backup reg is held under your chin on a loop of surgical tubing. The long hose goes down your back on the right, comes to the front near your hip, then crosses your chest and goes over your left shoulder, behind and around your head and forward again to the reg. To donate it, you duck your chin and lift the loop of hose over your head.

Submersible pressure gauge. Instead of a traditional gauge console, DIR divers use a simple pressure gauge on a hose just long enough to reach your waist, where it hangs from your belt on the left.

If you don't need it, leave it. Minimalism leads to streamlining and less effort expended, less chance of confusion.

Who Uses DIR?

DIR was developed by the divers of the Woodville Karst Plain Project, an expedition to explore the far reaches of inter-connected fresh-water caves in North Florida. Reducing the huge risk of these dives requires close teamwork and careful attention to details.

DIR is also at the heart of training standards used by Global Underwater Explorers (GUE), an organization for divers interested in exploration, and a training agency. In addition to technical training, GUE also offers basic open-water certification that incorporates DIR.

Jarrod Jablonski, GUE president, co-founder of WKPP, and a chief proponent of DIR diving, believes that dive training has gone soft in trying to make it attractive to everyone. "Too many divers are not given enough training to feel comfortable in the water," he says. "So they stop diving."

GUE believes every diver, even the beginning recreational diver, is better off in the DIR "mindset" and equipment configuration. Does that mean equipping yourself like Edmund Hillary to take a walk in the park? "Affirmative!" say DIR true-believers. "Get with the program or get out of the water." Jablonski, however, is less dogmatic. "We have a niche," he says, "for the divers who want our kind of training."