Ask an Expert: Should You Spearfish on Scuba?

Spearfishing on Scuba

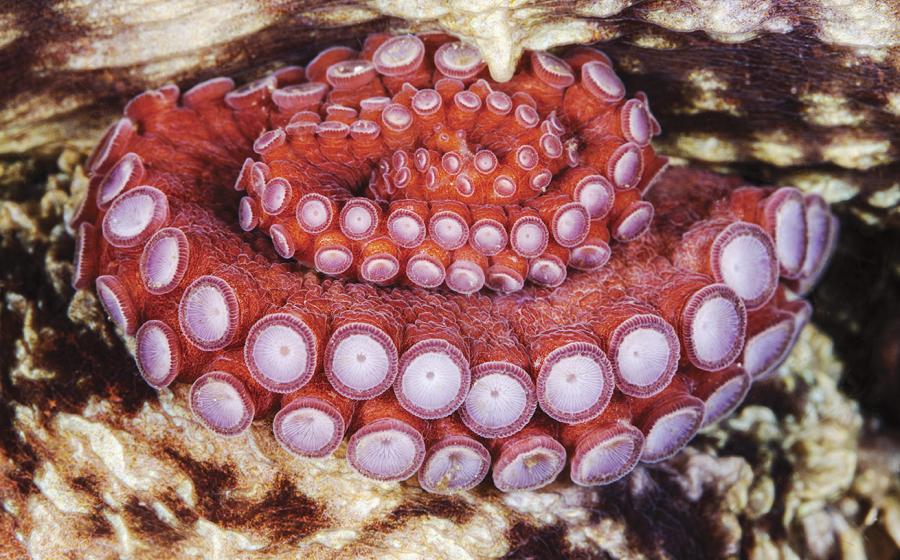

Masa Ushioda

Spearfishing on scuba is safer, more responsible and ultimately better for the environment. By John Conley

Jon Conley has been a weekly, year- round recreational spearfisherman in southeast Florida for the past 15 years. With well over 1,000 dives, his refrigerator is rarely empty.

Spearfishing on scuba is different from free-dive spearfishing for many reasons. The biggest differences are that spearfishing on scuba is safer for the diver, and it affords the most productive time to be selective of both size and type of fish — meaning zero bycatch (which is the unintended capture of nontarget species, and is a pervasive problem in that it now exceeds global target catch). I spearfish in Florida, and when I head out to target fish for dinner, I have to overcome many obstacles. For starters, depths range from 85 to 130 feet — well beyond the average breath-hold limits. A dive to these depths could result in injury for the novice free diver. At different times of the year, we can also encounter limited visibility and swift currents that could pull the observer diver — there to help in case of a shallow-water blackout situation — on the surface away from the free diver below.

In addition, we have convergent currents that bring in aggressive sharks like bulls, dusky reefs and sandbar sharks. If you flee to the surface because of breath- hold limits instead of backing the sharks off below at depth, you might get only one chance to show that this isn’t a free meal, thereby risking an attack.

While some might argue that spearfish- ing on scuba is somehow “unfair” to the fish — that it’s easier for the diver — that’s only half of the story. Fish are sensitive to bubble vibrations and have very keen eyesight. Blow bubbles underwater, and fish will know that you’re in proximity well before you can see them. Every bubble, every metal clip clang and every puff of air into your BC spooks the fish. Sure, scuba allows you to remain underwater for longer periods of time than a free diver, but you need that time in order to properly stalk the fish.

That’s a good thing for the environment, because spearfishing on scuba allows me to be more selective in evaluating the fish I want to target. Additionally, I have more time to measure, determine species and to conform to regulations without being worried about available air in my lungs. For example, many groupers have the ability to change their color, which could cause me to misidentify the species. This would be problematic if I were free diving and accidentally targeted a species that is illegal to catch because I was low on air. Scuba allows me to take the time to be sure before taking aim.

Spearfishing on scuba doesn’t give the spearfisherman too big of an advantage, because bubbles and noise spook fish. But scuba is safer for the diver, while allowing him more time to be selective on what he targets and catches.

Spearfishing with scuba changes fish behavior and impacts populations, negatively. By Samantha Whitcraft

Samantha Whitcraft is a marine-conservation biologist who has both studied and managed marine protected areas for the state of Hawaii and for NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service.

The long-standing argument in favor of spearfishing is that it’s highly selective and therefore avoids the massive waste of many commercial fisheries in the form of bycatch. However, spearfishing both on scuba and on breath-hold should more fairly be compared with other recreational catch methods. In hook-and-line fishing and breath-hold spearfishing, part of the framework for sustainability, in addition to laws and regulations, is 1) challenge and difficulty; 2) randomness of catch; and 3) depth limitations. Given a spear and a tank, it’s far easier to find the specific species and even animal that you want than by casting a hook and line or searching for a few minutes while holding your breath.

This enhanced targeting means that prized species (groupers, snappers, hogfish) will be more impacted, and the largest allowable fish will be preferred. Recent studies reveal that the larger fish in most populations are the most productive breeders, so removing them can severely impact pop- ulation growth. Selective catch, therefore, also has its ecological costs. Additionally, your average hook-and-line fishing or breath-hold diver has a shallower catch range than a diver on a tank. Scuba divers can continually spearfish at depths that could have served as a refuge for fish that were deep enough to avoid the hook or your average free diver. Furthermore, hook and line allows for catch-and-release fishing while spearfishing on scuba does not.

Interestingly, a 2008 study in the Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom found that sea breams in areas targeted by spearfishing exhibited an altered “escape response” by swimming out to open waters rather than seeking rocky shelter. Why is this important? For two reasons: 1) The study suggests that spearfishing, especially on scuba, alters the natural predator-evasion response of some fish — meaning that there could be impacts to the populations even when spearfishing is not directly involved; and 2) Fish might avoid any scuba diver, not just those with spears. This raises the question: Is it fair to the divers who want to see fish to make their dive sites about seafood? It is worth noting that many countries have banned or severely restricted spearfishing on scuba including much of Europe, Mexico and Belize, and recreational divers have reported enjoying increases in fish after such bans were instituted.

Finally, a 2009 study in the Journal of Applied Ecology found that resource managers could help temperature-stressed reefs and aid in recovery from coral- bleaching events by restricting specific gear such as spearfishing and traps. The researchers determined that these gear types, used both with and without scuba, targeted groups of fish that were vital in providing grazing and other functions important for ecosystem balance. In short, examples from successful bans and scientific studies strongly suggest that spearfishing on scuba, particularly, can have negative impacts on our fish populations and their habitats. And all scuba divers want healthy fish populations for everyone’s enjoyment long term. The most sustainable way to shoot a fish is with a camera, and far more challenging than with a spear and a tank.

Masa Ushioda

Spearfishing on scuba is safer, more responsible and ultimately better for the environment. By John Conley

Jon Conley has been a weekly, year- round recreational spearfisherman in southeast Florida for 20-plus years. With well over 1,000 dives, his refrigerator is rarely empty.

Spearfishing on scuba is different from free-dive spearfishing for many reasons. The biggest differences are that spearfishing on scuba is safer for the diver, and it affords the most productive time to be selective of both size and type of fish — meaning zero bycatch (which is the unintended capture of nontarget species, and is a pervasive problem in that it now exceeds global target catch). I spearfish in Florida, and when I head out to target fish for dinner, I have to overcome many obstacles. For starters, depths range from 85 to 130 feet — well beyond the average breath-hold limits. A dive to these depths could result in injury for the novice free diver. At different times of the year, we can also encounter limited visibility and swift currents that could pull the observer diver — there to help in case of a shallow-water blackout situation — on the surface away from the free diver below.

Courtesy imageJon Conley

In addition, we have convergent currents that bring in aggressive sharks like bulls, dusky reefs and sandbar sharks. If you flee to the surface because of breath- hold limits instead of backing the sharks off below at depth, you might get only one chance to show that this isn’t a free meal, thereby risking an attack.

While some might argue that spearfish- ing on scuba is somehow “unfair” to the fish — that it’s easier for the diver — that’s only half of the story. Fish are sensitive to bubble vibrations and have very keen eyesight. Blow bubbles underwater, and fish will know that you’re in proximity well before you can see them. Every bubble, every metal clip clang and every puff of air into your BC spooks the fish. Sure, scuba allows you to remain underwater for longer periods of time than a free diver, but you need that time in order to properly stalk the fish.

That’s a good thing for the environment, because spearfishing on scuba allows me to be more selective in evaluating the fish I want to target. Additionally, I have more time to measure, determine species and to conform to regulations without being worried about available air in my lungs. For example, many groupers have the ability to change their color, which could cause me to misidentify the species. This would be problematic if I were free diving and accidentally targeted a species that is illegal to catch because I was low on air. Scuba allows me to take the time to be sure before taking aim.

Spearfishing on scuba doesn’t give the spearfisherman too big of an advantage, because bubbles and noise spook fish. But scuba is safer for the diver, while allowing him more time to be selective on what he targets and catches.

Spearfishing with scuba changes fish behavior and impacts populations, negatively. By Samantha Whitcraft

Samantha Whitcraft is a marine-conservation biologist who has both studied and managed marine protected areas for the state of Hawaii and for NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service.

Courtesy imageSamantha Whitcraft

The long-standing argument in favor of spearfishing is that it’s highly selective and therefore avoids the massive waste of many commercial fisheries in the form of bycatch. However, spearfishing both on scuba and on breath-hold should more fairly be compared with other recreational catch methods. In hook-and-line fishing and breath-hold spearfishing, part of the framework for sustainability, in addition to laws and regulations, is 1) challenge and difficulty; 2) randomness of catch; and 3) depth limitations. Given a spear and a tank, it’s far easier to find the specific species and even animal that you want than by casting a hook and line or searching for a few minutes while holding your breath.

This enhanced targeting means that prized species (groupers, snappers, hogfish) will be more impacted, and the largest allowable fish will be preferred. Recent studies reveal that the larger fish in most populations are the most productive breeders, so removing them can severely impact pop- ulation growth. Selective catch, therefore, also has its ecological costs. Additionally, your average hook-and-line fishing or breath-hold diver has a shallower catch range than a diver on a tank. Scuba divers can continually spearfish at depths that could have served as a refuge for fish that were deep enough to avoid the hook or your average free diver. Furthermore, hook and line allows for catch-and-release fishing while spearfishing on scuba does not.

Interestingly, a 2008 study in the Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom found that sea breams in areas targeted by spearfishing exhibited an altered “escape response” by swimming out to open waters rather than seeking rocky shelter. Why is this important? For two reasons: 1) The study suggests that spearfishing, especially on scuba, alters the natural predator-evasion response of some fish — meaning that there could be impacts to the populations even when spearfishing is not directly involved; and 2) Fish might avoid any scuba diver, not just those with spears. This raises the question: Is it fair to the divers who want to see fish to make their dive sites about seafood? It is worth noting that many countries have banned or severely restricted spearfishing on scuba including much of Europe, Mexico and Belize, and recreational divers have reported enjoying increases in fish after such bans were instituted.

Finally, a 2009 study in the Journal of Applied Ecology found that resource managers could help temperature-stressed reefs and aid in recovery from coral- bleaching events by restricting specific gear such as spearfishing and traps. The researchers determined that these gear types, used both with and without scuba, targeted groups of fish that were vital in providing grazing and other functions important for ecosystem balance. In short, examples from successful bans and scientific studies strongly suggest that spearfishing on scuba, particularly, can have negative impacts on our fish populations and their habitats. And all scuba divers want healthy fish populations for everyone’s enjoyment long term. The most sustainable way to shoot a fish is with a camera, and far more challenging than with a spear and a tank.