Cave Diving the Intricate Underwater Passages of Missouri's Roubidoux Spring

Jennifer IdolDESCENT INTO DARKNESS

Cave diving at Missouri’s Ever-changing Roubidoux Spring is never the same twice, creating a thrilling opportunity for discovery every time. Photographers, read Jennifer Idol's photo tips for cave diving here.

Local fishermen stand downstream from the mouth of Roubidoux Spring, hoping to catch a few trout. Families and joggers run by and gawk as divers arrive at the headwaters. They’ve seen divers here before but still find us striking as we embark into the unseen. We bring truckloads of equipment and appear to be preparing more for a space mission than a scuba dive. Appealing, challenging, rewarding: Diving Roubidoux is all this and more.

To accept the myriad risks involved with cave diving, I needed a reason.

I once had proclaimed that I would never dive in caves. But a dive on the USS Oriskany changed my perception — and provided me with that reason.

Shannon Wallace, a cave-diving instructor, was on that Oriskany dive and noticed my penchant for photography. He casually said that he knew of a dive site that was home to a fish that had never been photographed. Even better, he alone had access to the site and could show me this fish. Hooked, I eagerly expressed my interest. The catch: I would need to become cavern-certified to make it happen.

I love learning, so I said I’d be happy to take the class. Cavern diving seemed an acceptable risk — I would always be within sight of an exit.

Shannon added that I should complete Intro to Cave if I was to be certain of photographing the fish. Pausing a moment, I agreed to take this class as well. Finally, he said Full Cave was not much different from Intro to Cave and I might as well take that too.

Months later, as a fully certified cave diver, I was ready to photograph the elusive creature I’d been training to find. I never did see the fish at that site — which was indeed a cave — but I did learn about a new world of beautiful sites. My first cave dive in Missouri took me past the light zone of a cavern and into the seemingly endless passages of Roubidoux Spring.

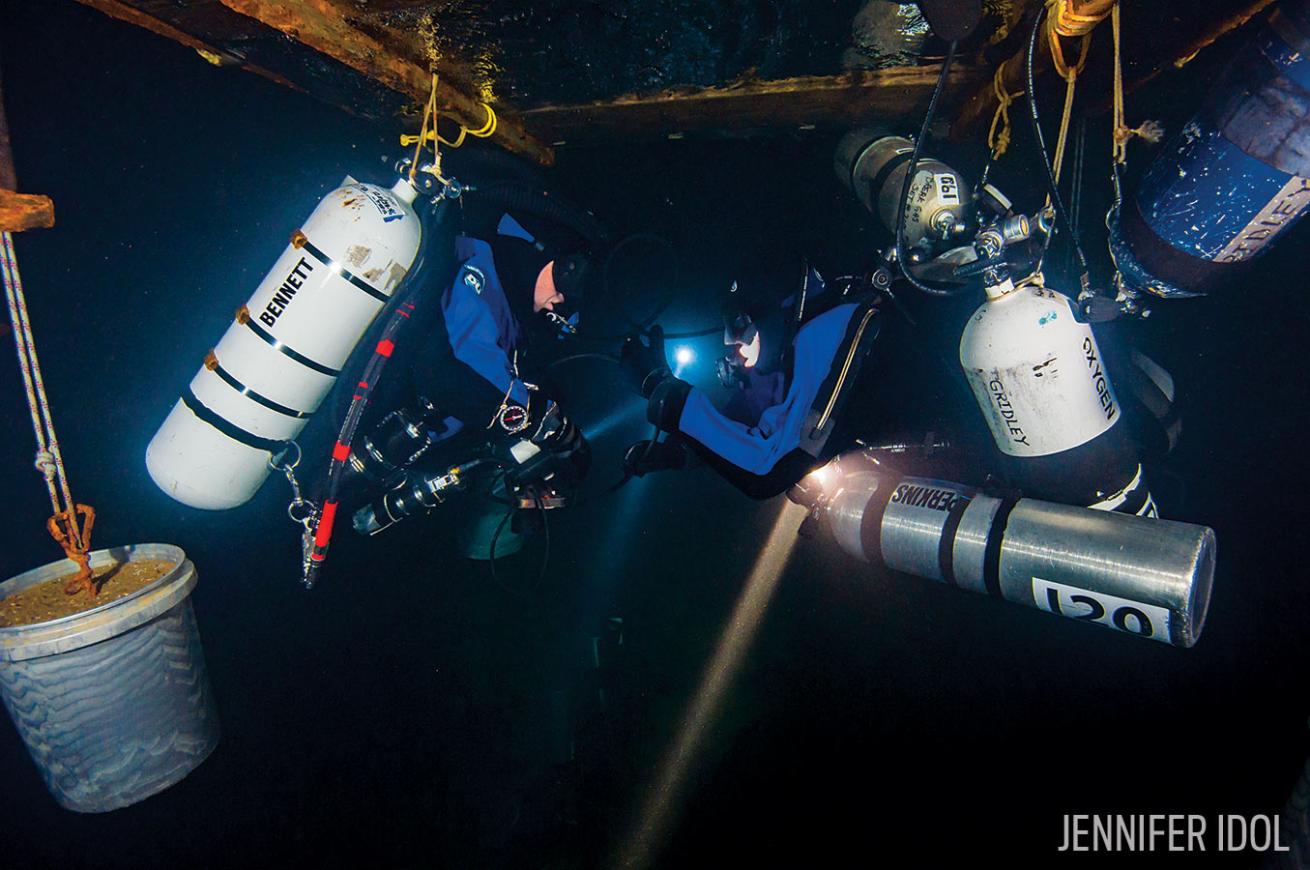

Jennifer IdolDuring the 10 hour decompression, divers enter this manmade habitat where they can eat and breathe dry air while still 20 feet underwater.

THE ROLES OF EACH DIVER

Every diver has an essential role critical to making cave dives successful and safe. Surface managers record bottom times, monitor plans and coordinate support-diver times. Support divers position additional cylinders at specific places within the cave for the exploration divers.

I participate as a support diver with a specialty in photography. I’ve made up to eight support dives in a day, then made successive dives to photograph activities and parts of the cave. I often make these dives shuttling between the entrance and the precipice above the lower tunnel.

I have helped place decompression cylinders near the front of the cave to be used on the exploration divers’ exit. Nearly 10 hours of the dive is dedicated to decompression for exploration divers, elevating the risk of this portion of the dive. The lengthy decompression time is a result of Roubidoux’s depths, which reach a staggering 270 feet.

Missouri diving is cold, which can also increase risk for decompression sickness. We wear drysuits with thermal protection in the 50-degree water. Exploration divers wear heated vests and typically exhaust the battery power limits. We leave additional batteries for their return to help them warm up during deco.

With so much time in the water, it’s important to stay hydrated, so we help exploration divers into a habitat where they can eat and drink in dry air while still at 20 feet. The team built this environment (which looks like a small submersible) with a hole in the bottom to shuttle divers through. This permits divers to decompress in a warmer air environment while at depth. They remain on oxygen in the habitat to continue effective decompression.

Jennifer IdolTo ensure the safety of the exploration team, support divers position additional cylinders throughout the cave and cavern system.

GOING A LITTLE FURTHER

Cave diving is a progressive activity in both training and experience. As I became more proficient, I joined the Ozark Cave Diving Alliance — a team formed in 1998 — to build my skills and contribute to the team through my photography. Taking photos in caves is challenging because the only available light is what you bring with you, and camera equipment adds task loading in an already complicated, stressful environment.

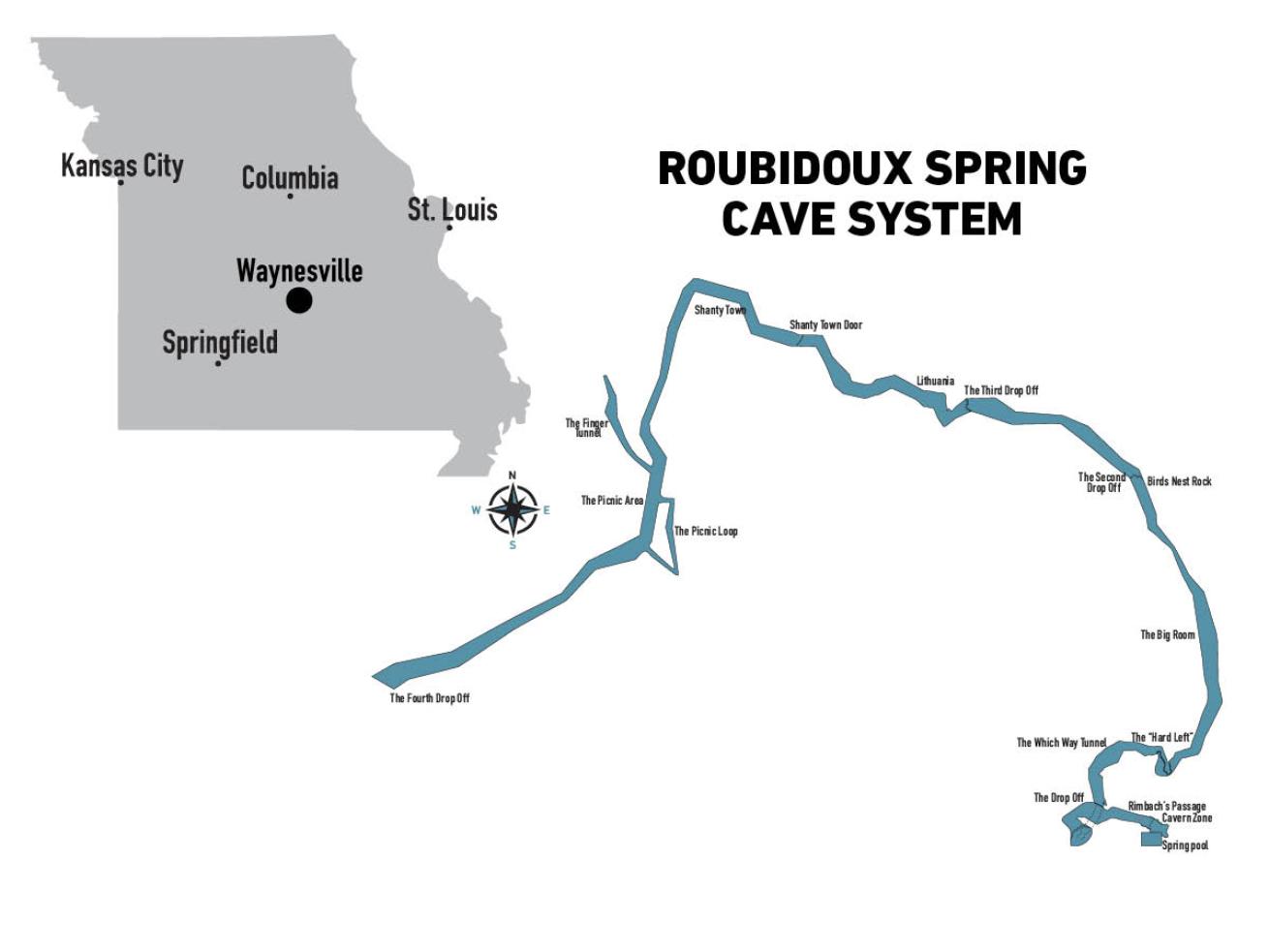

OCDA is named for diving locations around the Ozark Mountains of Missouri, home to karst features that form more than 6,000 documented caves. Many are submerged and accessible only through diving.

Permits allow the OCDA legal access to sites otherwise prohibited from public diving. One of those is open to qualified divers: Roubidoux Spring in Waynesville, Missouri.

OCDA maintains a permit that allows us to dive the site beyond the hours open to the public — necessary because the team has explored Roubidoux to 11,256 feet. Such a dive takes 16 hours to complete, well beyond the time the spring is open to cave divers. We continue to push the cave because it continues for an unknown distance and is far from walled out. Semi-closed rebreathers help exploration divers extend their available gas, and diver-propulsion vehicles help divers and support members reach distances twice as fast as if they were finning.

Jennifer IdolThe limestone walls inside Roubidoux’s cave system don't reflect light well, so it can be a challenge to see.

WHAT THE CAVE SYSTEM IS LIKE

Missouri caves are similar to one another, featuring small openings through high flow with dark passages that quickly become deep. Conditions are limited by the rainy season, so most dives take place from August to March. Rains turn Missouri caves into volatile conduits for mud that would challenge whitewater rafters — flow for Roubidoux averages 37 million gallons a day, a rush to push through on a normal day.

From the surface, the small entrance is hardly visible. I descend into the spring pool and enter with my camera cradled in my arms, towing the DPV behind me, pulling myself against rocks on the floor. Once my back touches the ceiling, I can use my feet to push fully into the cavern. The flow is strongest through the small opening and relaxes inside the big cavern room. The rush of entering the cave raises my breathing and heart rate, so I take a minute to reset my buoyancy, breathe, and set up my camera and DPV.

Once neutrally buoyant, I signal to my buddy, who is also orienting himself to the cavern. I pause to take photos as more divers enter the cavern. Though rocky, the clear cavern will soon appear smoky from the silt-stirring activity — rocky formations on the sides of the cave are covered in fine dust. We circle “OK” with our lights and head toward the grim-reaper sign indicating the end of the cavern zone. Though the tunnel here is smaller than the cavern, the water does not flow as strongly as it did through the entrance.

I take time to observe limestone walls carved over time by turbid water during the rainy season. Some of the walls appear like popcorn, while others look more like stratified lines. One curved section of the ceiling looks like an upside-down horseshoe.

As I travel down the main line, a jump to a side passage is possible early in the cave. However, I continue toward the downward spiral, aptly named the Which Way (Lower) Tunnel Entrance. The tunnel corkscrews to the main corridor, which continues for a downward-sloping 140 feet. I enjoy looking across the chasm in this section because it represents the unknown ahead, beckoning me onward. Enveloping blackness in this room intensifies the feeling of smallness in an immense cave system.

Though formed from limestone, Roubidoux is very dark. The walls reflect little light, so I bring big strobes and video lights into the cave. The best visibility I’ve seen reaches 30 feet but is more commonly half that distance. The darkness draws my eyes directly to the subjects my lights illuminate, as if on a night dive. Visibility appears better than it is, until my camera strobes reveal smoky passageways. Passing divers disappear quickly into darkness, though they carry 50- and 100-watt lights.

Jennifer IdolDivers on the Ozark Cave Diving Alliance Team use diver-propulsion vehicles (DPVs) and semi-closed rebreathers to explore the cave system.

The lure of photographing passageways like those found in Roubidoux Spring compels me to return each season. I am excited by the opportunity to discover new structures and find the few blind crawfish that inhabit Roubidoux. Since the conditions in Roubidoux are always changing, no two dives here look the same. The cave appears to always be changing, creating a thrilling discovery each time.

My favorite dives are the ones when I have been working hard with the OCDA because I work toward a goal that supports exploration and conservation of Roubidoux Spring with a group of fun and talented divers, a rewarding challenge for any qualified diver.

Monica AlbertaA map of Missouri next to the mapped cave system in Roubidoux Spring.

DIVE CONDITIONS: ROUBIDOUX CAVE, MISSOURI

When To Go: Dive between August and March for optimal conditions. The rainy season prohibits diving outside dive season due to diminished visibility and high flow, but rains might make conditions difficult at any time. Check weather reports for rain in the forecast before leaving to dive. The recharge zone for the cave sends water through the system within days of rain.

Diving Conditions: Expect visibility from 5 to 30 feet and high flow. Temperatures range from 48 to 56 degrees F.

Gear Needed: A drysuit and hood are necessary. Dry gloves also might be worthwhile.

Dive Shop: There is no on-site dive operator. To get permission, check in and present your certification at the Pulaski County 911 Communications Center, 1500 Ousley Road, Waynesville. For information or if you’ve got any questions, call the Waynesville Police Department at 573-774-2414.

Price of Diving: While no fee is required to enter Roubidoux Spring, the cost of certifications and the required equipment can be significant. Progressive learning distributes cost as well as experience.

More Info: Ozark Cave Diving Alliance, ocda.org

Jennifer IdolWhile the surface of Roubidoux Spring is calm, entering the cave system means pushing past a spring that produces 37 million gallons of water per day.

TIPS FOR DIVING THE CAVE SYSTEM

The cavern is a small area with the cave sign within the first 80 feet of the entrance, so at least an introductory cave certification is recommended. Depths reach 141 feet within the first 475 feet of the cave, so additional mixed and decompression gases and training need consideration.

Always check in at the Pulaski County 911 Communications Center next to the Waynesville Rural Fire Protection building off Route 66 before and after your dive to show certification cards and sign a release form. Diving must take place during daylight hours.

The hill near the parking area at Roy Laughlin Park is steep, so consider bringing a dolly to transport doubles.

Stage gear in the shallow area next to the cement pad in front of the spring pool. Get into gear in the pool, and walk until the water becomes deeper. Then, descend and enter the cave below the center of the retaining wall.