What It’s Like to Warm Water Dive For the First Time as a Cold Water Diver

I have lived in the Sunshine State for just over a month when I finally reach its eastern coast. Fun diving has taken a backseat recently, replaced with rebuilding flat-pack furniture, unboxing my favorite books and non-stop cleaning as I relocated from Washington State] for my new job with Scuba Diving magazine.

Despite feeling exhausted at the end of each day, I am still open-minded and optimistic about my new life in Florida—humidity, giant cockroaches and all. My heart hasn’t yet felt the first pangs of longing for the gentle rain, emerald green waters and thick dark Douglas-fir forests of the Pacific Northwest.

Candice LandauThe Blue Heron Bridge

Above all else, I am hungry to experience good visibility, warm water and marine life I couldn't hope to name. I am also eager to shed my heavy cold-water diving equipment—a bulky drysuit, hood, gloves and heavy fins, not to mention what often feels like a literal ton of lead.

When I show up at Blue Heron Bridge on PADI’s 2022 Women’s Dive Day, I am greeted by Seminole Scuba shop staff. The group assembling dive gear is wearing far less clothing than I am used to—bikinis and rash guards, freediving wetsuits and flip flops. I feel out of place as I stretch my warm 5mm wetsuit over sweat-slick skin.

The gray concrete of Blue Heron Bridge arcs above me. Nothing about it makes me think of herons or the color blue, yet my pulse slows as a sense of peace takes precedence. The water is turquoise, not the green I am accustomed to, and the shore entry is beach sand, not a slew of rocks, mud and pine needles.

As I submerge I am surprised to feel no relief from the heat. I hear someone say the water temperature is 85 degrees Fahrenheit. It’s a number that boggles my mind. This is already a far cry from the waters of the Puget Sound, which average 55 degrees most days, and offers a comparative relief when you’re in a thick drysuit and dense fleece undergarments. I’m already learning: Next time I will be in a 3mm wetsuit or a dive skin.

After a briefing, the group jets off to the far west side of the bridge to drop and drift as the tide turns. My buddy and I diverge, dropping closer to shore. We are too hot for a long surface swim and the whole site is shallow and tropical. How wrong can we go?

Courtesy ImageThe author (right) poses in her drysuit with her dive buddy, Devina.

I sink like a stone. Way too much weight. I make a mental note to remove four pounds the next time around. Spooling out my dive flag—a required piece of dive equipment at this site—I cheat a little and use it to stabilize my buoyancy.

For a few seconds I hover motionless, slowly getting used to the incredible visibility. It’s a far cry from a typical day in the Florence North Jetty in Oregon where visibility might be anywhere from two feet to 10 feet.

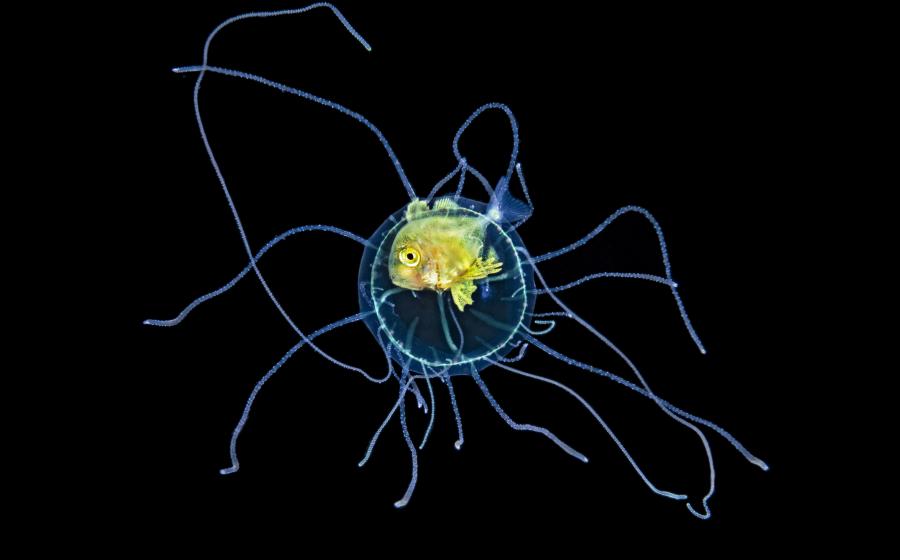

Below me the sand is white, a net of light playing over it. Here and there strange pink sponges I can’t name poke from the sea floor. We soon happen upon a small wreck, immediately alluring for hosting the first tropical marine life I see in the wild. A black and yellow angelfish of some sort, followed by a barracuda (I had no idea you could find them in shallow water), a pink moon jelly and a funny fuzzy little red and white worm. I am bowled over. In between each breath, I hear a gentle crackling. I’ve watched Saving Atlantis and Chasing Coral so I know, intellectually, that this is what a reef sounds like. But to hear it firsthand is mesmerizing. I attempt to convey “listen to the noise” to my buddy but fail miserably. He spends the next minute asking if my ears are “okay.”

As we continue our dive, I come across more marine life I do not know, corals and bryozoans, and some fishes that also look remarkably similar to the sculpin and cabezon of the West Coast. Somehow, this makes it easier to accept the fact that I will no longer be seeing giant Pacific octopus or wolf eels or the curious copper rockfish I have grown to adore.

Candice LandauLandau's cold water gear spread on her deck. She quickly learns this is significantly more equipment than she'll need in warm waters.

I am not wearing gloves as I own no pair thinner than 5mm. Given the abundance of unknown life, I am very reluctant to put my finger on anything, even if just to steady myself. I don’t yet know what stings out here and make another mental note to pick up a pair of super thin gloves, just in case.

As I drift past another structure, I see a familiar glint in the water. It’s a line of discarded monofilament attached to a fishing hook. Instinctively I reach for my pocket on my wetsuit, only to realize it doesn’t exist. Another reminder I am no longer in my heavily-equipped drysuit.

An hour in, I feel the current picking up. I signal my buddy to turn the dive. When I look back around I am forced to come to a stop. Not ten feet ahead a vast cloud of silt obscures our progress. I stare into it trying to determine the cause.

My heart jumps into my throat when I see something shuffling in the sand. It takes my brain a good few seconds to wrap around what it is. A mermaid? A struggling diver? An animal? Slowly the shape takes meaning and I make out wings and a long tail.

I gasp through my regulator, whip around and grab my buddy’s arm to make sure he is seeing what I am. It’s a ray digging through the sand, stirring it up with its odd triangular wings.

Suzan MeldonianA spotted ray arcs through the water.

I am frozen in disbelief and exhilaration. This is a spiritual moment—a wild animal foraging near me, heedless of my presence. In the hundreds of dives I have done to date, I have never seen a ray.

A small part of me wants to cry. The ray picks up and flaps slowly over the short seagrass, settling once more into the sand to rummage for food. Its large eyes are full of expression and I think it knows we are watching it. When it finally disappears into the haze of blue below the boat channel, we begin our return to shore. My heart is still throbbing, aching with appreciation and myriad other emotions I can’t name.

We surface with huge, deep-set grins that cause water to seep into our masks. Still, nothing can diminish this joy. This isn’t the gritty shore dives of Tacoma that I was growing to love, but I think I will be okay.