"Living Seawalls" Provide New Homes for Coastal Marine Life—And They're Going Global

Courtesy Living SeaWallsThe addition of the concrete panels creates greater species diversity and abundance, which the team can track over time to gather data.

Sydney, Australia is one of the world’s most picturesque cities, its iconic Harbour Bridge and Opera House instantly recognizable. But what’s happening underwater in this harborside city is a bit more under the radar.

Recent aquatic installations on the Sydney Harbour foreshores are helping to restore marine biodiversity, an innovation that is now attracting global recognition.

Sydney’s landmarks now form a backdrop to 11 harbor sites sporting “Living Seawall” installations—three-dimensional concrete panels designed to mimic natural foreshore environments such as oyster beds, rock pools and mangrove roots.

The Living Seawalls project is a collaboration between the Sydney Institute of Marine Science, Macquarie University and the University of New South Wales. It aims to address the global boom in marine-based infrastructure, as well as declining rates of marine biodiversity.

Coastal Construction on the Rise

There is now more seafloor area modified by built infrastructure than area taken up by our planet’s mangrove forests and sea grass beds.

“There is an ongoing construction boom in our seas, from seawalls, pilings, pontoons and marinas to offshore wind turbines, aquaculture developments and mining rigs,” says project co-leader and Macquarie University associate professor Melanie Bishop. “This is hugely detrimental to marine ecology, often in the harbors, estuaries and coastal fore- shores that are the nurseries and food sources for most oceanic life.”

Rising sea levels and storm surges often prompt proactive reinforcement to protect coastal assets, explains Bishop. “Ironically, replacing natural defenses with hard seawalls can make coastlines more vulnerable to climate-change-exacerbated events.”

Together with a team of international collaborators, the Sydney-based group found that in 2018, marine structures had a global footprint of over 32,000 square kilometers, or about 12,300 square miles. Researchers estimate that over the next decade, the area of seascape modified for power and aquaculture infrastructure, cables and tunnels will increase by at least 50 percent.

Courtesy Living SeaWallsSome seawall panels are attached with stainless-steel rods, allowing them to stick out from the wall and create more surface area.

Sydney Harbour is a great example of this construction uptick, with over half the foreshore now modified by seawalls, wharves and other structures. The oyster reefs that historically dominated the shorelines have all but disappeared.

Mimicking Coastal Habitat

Working in collaboration with industrial designer Alex Goad and the Reef Design Lab, the Seawalls team has so far designed 10 different habitat surfaces, using 3D printing to create original molds to cast the concrete panels, which are around a foot and a half in diameter.

The panels can be retrofitted onto existing seawalls, simulating a natural shoreline ecosystem that provides habitats for organisms such as fish, algae and invertebrates. Bishop says that after just two years, the panels already support at least a third more species on them than had been there for decades. “Since many of the organisms are filter feeders like oysters and barnacles, the water quality of the harbor improves.”

“We have seen more than 90 species colonizing these diverse panels, and we see 30 to 40 percent more species on the panels in the Living Seawalls than on the unmodified parts of the seawall,” says project co-leader Dr. Mariana Mayer Pinto, a professor at UNSW. The team also witnessed more than 30 species of fish using the habitat as both shelter and feeding grounds.

Rather than attaching all of the panels flat against the wall, the team triples the surface area of the reef by attaching some panels to stainless-steel rods that create distance—about 4 inches— between the panel and the wall where organisms can attach. The cavity behind the panel also provides an attractive place for fish to forage, Pinto says.

The modular design allows the Living Seawalls to be tailored to each site, and as sea levels rise in coming years, they can provide habitat for species to migrate vertically.

And this is not the only way the installations can provide protection to marine life from climate change. Seawalls and other structures are bare, featureless surfaces with little protection from the high temperatures that can occur at low tide in summer, but these panels can reduce surface temperatures by as much as 18 degrees Fahrenheit.

“In a warming climate, this can be the difference between life and death for a lot of species, so the panels can form part of our climate-change adaptation,” Bishop says.

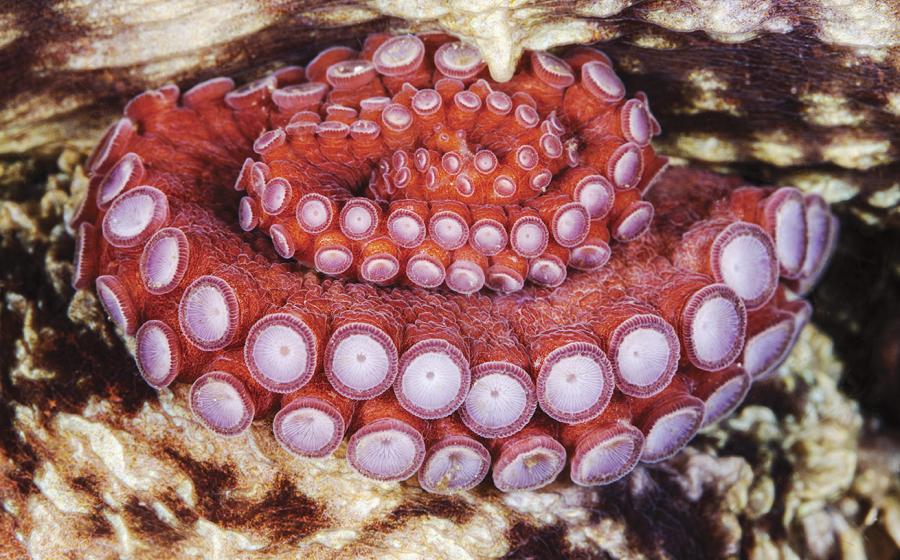

Courtesy Living SeaWallsA close up of Living SeaWalls structure.

Going Global

In addition to the 11 Sydney Harbour locations, installations have been constructed in South Australia’s Port Adelaide, Narooma on the New South Wales southern coast and Townsville in Queensland.

The panels are being piloted outside of Australia at sites in Singapore, Gibraltar and Wales.

The project has attracted international acclaim, selected as one of 15 finalists for the Earthshot Prize by the Royal Foundation of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge, and there are now more than a thousand panels installed globally.

“By using good science and designing our marine infrastructure with nature in mind,” Bishop says, “Living Seawalls has enormous potential to increase the ecological and social value of coastal structures worldwide.”