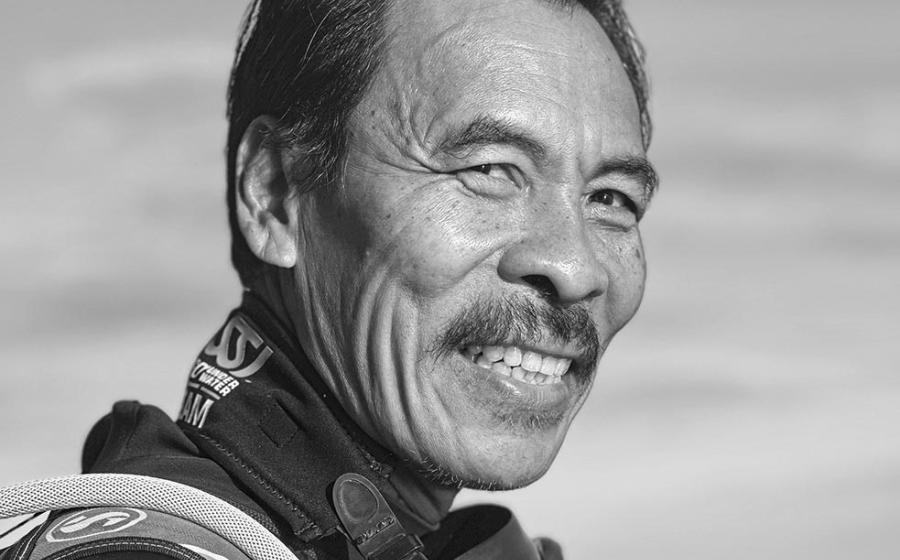

Shark Conservationist Randall Arauz Earns Sea Hero Honor

Courtesy Randall ArauzZeroing in on overfishing in the Eastern Pacific, and why it has to stop.

Biologist and conservationist Randall Arauz has made almost 40 trips to Cocos Island in the last 15 years. What he has learned there has given him his life’s purpose: to stop overfishing and illegal fishing in the Eastern Tropical Pacific, using scientific data to try to persuade governments to change policies, thereby protecting the region’s magnificent megafauna for generations to come.

Q: You’ve been working in Cocos Island since 2004 — give us a snapshot of the changes you have seen there over time, and what you have learned?

A: I’ve been to Cocos Island on 39 expeditions since 2004 — and no two trips have been the same. There are seasons when wildlife is more abundant, typically during the rainy season, but overall, after 15 years of diving Cocos, I see some definite changes in marine wildlife abundance, particularly the species I’m interested in, turtles and sharks. On my first trips to Cocos Island, the walls of hammerhead sharks were countless — one would lose track after about 150 sharks. Silver tip sharks had their own specific hang-out or cleaning station, and encounters with sea turtles were common. Over the years, those incredibly large schools of hammerheads have slowly but steadily declined, with sightings less frequently reported in recent times. The silvertip shark cleaning station has disappeared, and sightings of the specimen are currently rare. Sea turtle sightings are less and less frequent — I haven’t reported a turtle sighting since 2016. But not all populations of marine life are declining in Cocos Island; tiger sharks have increased dramatically during the last few years; they were a rarely spotted species just 10 years ago, now regularly sighted.

Many factors influence the abundance of different marine species in Cocos Island. During recent years, pressure from illegal fishing has no doubt dropped — although it’s far from eradicated — which may be affecting greater tiger shark abundance. More sharks may translate into cascading effects on prey species, explaining their plummeting populations. Climate change and warming waters must also affect their migratory movements. (During the early months of 2015 I experienced unusually warm waters, up to 87°F at the surface, no need for a wetsuit.)

Natural cyclical predator-prey interactions may also be playing a role. We are just now beginning to understand these cascading effects, as well as the effect climate change may have on the future abundance of these species. Resilience of marine ecosystems to the onslaughts of climate change will depend on their ecological integrity, and thus, the presence of apex predators.

Q: What are the most critical issues for Cocos and the megafauna of the Eastern Tropical Pacific today?

A: Overfishing is no doubt the most critical issue. Regional political initiatives are designed to cater to fisheries’ interests. I have been advocating for many years now on the need to reduce fishing, the only solution that will work in an ecosystem context. Policy efforts, under pressure from the fisheries industry, are geared towards mono-specific solutions that allow fishing to continue unabated. Solutions are sought for sea turtles, or sharks, or the charismatic species of your choice, when the true issue is the ecosystem-wide impact of fisheries. It may not be politically palatable to reduce fishing by actually removing vessels from the ocean, but we can control fishing by creating larger no-take marine protected areas — the bigger the better — which have proven to be efficient for the conservation of endangered highly migratory species, and we can promulgate regional closed seasons for fisheries when certain commercial species are less abundant. It is well acknowledged that no-take policies in large MPAs even provide benefits to commercial fisheries that occur outside of them due to the spillover effect.

Q: Part of the impetus behind the Migramar consortium of scientists studying migration, which you helped found, is to gather data that governments can use to implement policy. Has this approach yielded success?

A: Certainly. Working through the various ministries of the environment of governments in the Eastern Tropical Biological Corridor, we provide the best information available for the establishment of conservation policies. With the information provided so far, some countries have moved forward by increasing the area covered by a no-take policy in the MPAs surrounding their islands in the ETP. Diplomatic initiatives are currently underway to connect several of these hotspots through corridors we call “swimways.”

As long as we work within the realm of these ministries, we can say some success has been attained, such as the recent expansions of the MPAs surrounding the Malpelo Sanctuary of Colombia and the Galapagos Reserve of Ecuador under a no-take policy, to 10,424 square miles and 51,351 square miles, respectively). Unfortunately, Costa Rica lags behind, with a no-take MPA surrounding Cocos Island National Park of slightly under 772 square miles. At Migramar, we are committed to generating the science for the Costa Rican government to justify the expansion of a no-take policy in waters surrounding Cocos Island as soon as possible.

Courtesy David GarciaArauz with a pole spear, used for tagging animals for scientific studies that he hopes will be used to influence conservation policy.

Q: How did you first get involved with Cocos? What are you most focused on now?

A: When I started my shark finning campaign in 2001, I had already amassed significant information on the impact of longline fisheries on sharks and sea turtles. However, I was working with dead sharks, which was a little disappointing. In 2004, I was invited by Alex Antoniou, currently with Fins Attached Marine Research and Conservation, a Colorado-based shark conservation NGO, to help him set up a shark monitoring program in Cocos Island in 2004. He offered everything I needed, from travel to Cocos to the donation of expensive acoustic tracking equipment; I have been directing this research project ever since. Turtles joined the focus of our studies in 2009.

Q: What do you view as the greatest challenges in marine conservation today? How are these challenges reflected in your own work?

A: The main challenge is achieving policy change — this is where it really matters. Typically when policy decisions are made, science rides in the back seat, and commercial fisheries’ interests prevail. I try to work with the government, and to do research to generate the best information available, compiling information and networking with top scientists in the region to provide conservation officers and fisheries managers with the best information available for the decision making process. However, when it comes to our fisheries’ policy, decisions have a tendency to not respect the science nor defend the public interest but rather to focus on the interests of the fishing industry.

This is when the final resource comes into play: the lawsuit. When everything else fails, we rely on the court system to defend public interest legislation, using the best scientific information available. This is the way I helped shut down a green turtle slaughterhouse in 1999, imposed a fins-attached landing policy for sharks in Costa Rica in 2006, shut down the operation of tuna farms in 2007, shut down private docks where Taiwanese shark finning fleets were illegally (yet under a policy of tolerance) landing shark fins without official scrutiny in 2010, and shut down the shrimp trawl fishery in 2013.

Q: What’s been your most satisfying moment?

A: I’ve had a few! The first was when we shut down the green turtle slaughterhouse in 1999. This was when we figured it out that if we have public-interest laws on our side, and we use the best available science to show how a certain private activity negatively impacts the public interest, we can actually change policy. The other satisfying moment came when we closed private docks to the landing of Taiwanese or any foreign fleets. This activity was forbidden by Costa Rica’s Public Transportation Law, but when confronted in 2004, the response of the authorities (Customs, Ministry of Public Transportation and Costa Rican Fisheries Institute) was that there were no public docks where these vessels could land under law, so they were allowed to use private docks, facilitating the circumvention of fisheries regulations such as the ban on landing shark fins. After a six year campaign, in 2010 the private docks were closed by court mandate.

Read More: Scuba Diving Sea Heroes

Q: What’s been your most surprising moment?

A: No doubt it was when Costa Rica declared that sharks weren’t wildlife, to circumvent CITES regulations. I didn’t see that one coming! I thought I had a grip on the situation, with the Wildlife Conservation Law as my battle horse, but the authorities figured out how to shoot that down and force us to go to a court process that will take another year or two to resolve. The power of the shark fishing and shark-fin exporting lobbies of Costa Rica over the government is overwhelming and appalling.

Q: Who are your sea heroes?

A: I admire Sylvia Earl, such an inspiration; I never miss a chance to listen to her when she speaks. There is no middle ground with her! She makes me want to go out there and change things for marine life now — I live by that! I also admire Jacques Cousteau. I always tell the story of how I would watch his show on TV when I lived in California. I must have been 8 or 9 years old and knew right away I wanted to dive and study marine wildlife, be a marine biologist. He inspired a whole generation of us.

Q: What can divers and our readers do to help further your work?

A: First of all, talk about these problems to your family and friends. Never consume shark products. Support legislation that restricts fishing of sharks and bans commerce in shark products. Support your local nonprofit organizations working to protect sharks. Come on a citizen science research expedition with Fins Attached Marine Research and Conservation on board the M/V Sharkwater to Cocos Island with me as your scientist guide! And of course you can follow me on Facebook for direct campaign updates.

Q: Is there anything we did not ask that you would like readers to know? Tell us what’s important to you!

A: This not a shark problem, nor a sea turtle problem. It’s an overfishing problem with ecosystem impacts, and the only ecosystem solution for endangered species like sharks is to stop killing so many of them through the reduction and control of fishing.