Afterglow in the Underworld

PROLOGUE

Shortly after World War II, the charming Polish town of Kowary — which had escaped the devastating effects of German bombs — welcomed a wave of migrants. Known as a mining center since the 12th century, Kowary had a rapidly expanding industry offering high-paying jobs. The state-owned Kowarskie Kopalnie mine was founded January 1, 1948; Stanisław Jasiński was one of the first miners to enter the shaft near the village of Podgorze. Jasiński was a laborer, with no qualifications in mining, just like his new colleagues. His tools were a pickax and shovel. Although he knew nothing about the ore he would dig, the ubiquitous Russian specialists, scientists and military guards from the Polish Internal Security Corps indicated that Podgorze was important. By signing a top-secret document, Jasiński committed himself to keeping quiet about what went on in the mine — colleagues who rashly opened their mouths while sipping vodka with friends disappeared in mysterious ways.

Yet those disappearances were not the only concerning phenomenon in Podgorze. Jasiński’s colleague Stanisław Moszkowski worked in the mine for five years, the last two spent sorting ore. Extracted stones were exposed to a Russian dosimeter. If the machine’s hand moved noticeably, the stone went on the pile on the right; if it didn’t, the stone was thrown on the left. After weeks of sorting, pieces of skin were peeling off Moszkowski’s hands like paper.

Anatol Moszkowski began working in the mine in radiometry when he was 18. He became friendly with a Russian engineer who shocked him with this advice: If you want to live, don’t go where the dosimeter’s hand oscillates much.

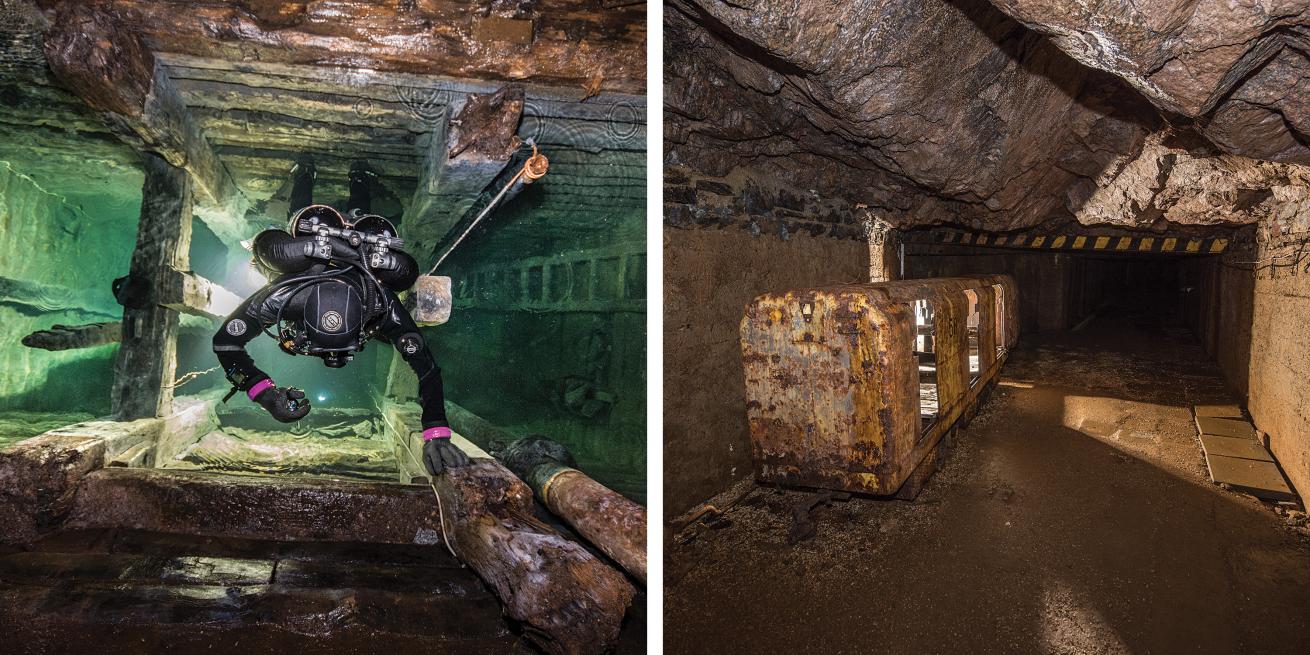

Martin StrmiskaAn abandoned train car that once transported workers marks the mine entrance.

By eight years later, the quality of ore extracted in Podgorze had degraded. The Russian engineers and Polish armed forces departed. Only then, after years of mining, did Jasiński and his colleagues learn the truth about what they had dug. What they had touched with bare hands was uraninite, or pitchblende, a radioactive, uranium-rich mineral and ore; the gas they breathed was radon.

Then, in 1963, all mining ended. The remaining miners were put on disability retirement, suddenly and in secrecy. A few years later, Jasiński was diagnosed with serious lung disease, and many others suffered the long-term consequences of radiation exposure — organ damage, platelet disruption, leukemia and other cancers.

IN THE BELLY OF THE BEAST

Martin StrmiskaDescending into the mine (left); radiation-detecting equipment.

The Giant Mountains — a range that runs from the Czech Republic through southwest Poland — is a natural treasure. Dense coniferous forests intersected by limpid streams, waterfalls and mountain walks attract tourists in warmer months, while several ski resorts are popular in winter.

In spring, the March sun doesn’t fully reach the northern side of Giant Mountains National Park. Podgorze is still under cover of snow, which renders the road from the village to the mine entrance impassable for normal vehicles. Luckily, mine manager Patryk Guzik has sent ATVs equipped with trailers, which comfortably bring us and our equipment to a small wooden structure in front of the mine entrance, where we tend to registration and the usual paperwork.

The cold penetrates our bones as darkness creeps out of the gloomy forest. Only a bright-yellow train car parked in front of the mine entrance seems cheerful. More than 70 years ago, the train brought miners through a 1,300-foot tunnel to the central shaft, where they dispersed to various levels in the mine.

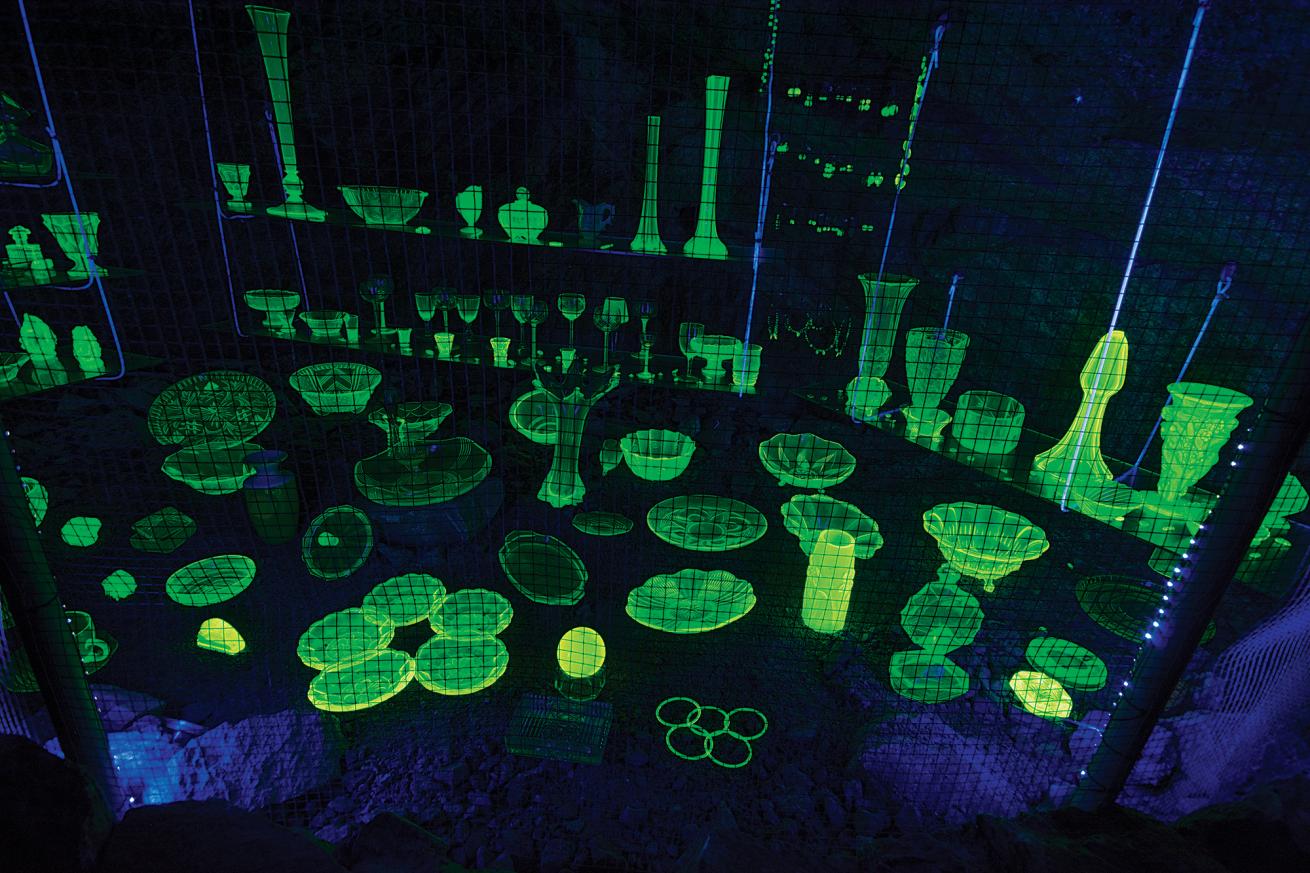

Today scuba divers follow the same route, with a stop first at a display of uranium glass — cups, plates and other objects made with trace amounts of uranium oxide shine yellow-green when exposed to ultraviolet light. Another stop is an exhibit of protective clothing used when working in a radioactive environment.

Martin StrmiskaUranium glass.

The dark story of the Polish miners is foremost on everyone’s mind, and a question hangs in the air — is there still a danger here? In fact, there is still radiation, but no longer at levels that would harm a visitor’s health.

The final station is the vertical shaft, the artery of the mine that connects 12 levels of tunnels. Water constantly seeps into the mine through cracks in the rock, forming a small creek in the main tunnel as it flows out.

When the mine closed down and pumps stopped draining groundwater in the 1960s, the shaft and lower levels were flooded.

SCENE OF THE CRIME

The room where the flooded shaft drops away looks scary. Water drips from dark walls into a small pool. At the entrance stands a replica of a Soviet atomic bomb — uranium extracted from this deposit was used to create those sinister weapons. The horrorlike scene is complemented by old ventilation pipes and a radiation suit with gas mask. A strange monotonous rumbling can be heard.

Underwater, the eerie rumbling subsides. We submerge using a vertical shaft lined with wood. It’s more than 1,700 feet deep but not wide enough for two divers abreast, so we descend one by one. Being confined in a chimney not wide enough to extend the body to trim position feels weird — the opening into the first-level tunnel, at about 100 feet, is a relief. Other tunnels branch out at 230 feet, 360 feet, 500 feet and deeper. At the bottom of the shaft are fins, stage tanks, lights and masks dropped by careless divers.

Martin StrmiskaOur unease is magnified by the deep shaft and quarter-mile-long tunnel between us and daylight.

The shaft itself is a sophisticated piece of woodwork incorporating tens of thousands of tree trunks; thousands more were used in the tunnels to create portals and support unstable ceilings.

Marian Michałek, who mined uraninite 70 years ago, remembered that sometimes it was enough just to hit the deposit of uraninite with a stick to knock it loose into the carriage. After a shower of slate, he would find himself in a cloud of black dust, the sweet taste of uranium shale on his tongue.

Today, pieces of slate fall through tree trunks onto divers. At the bottom, there is a layer of gray sediment, the formerly radioactive dust. Carefully passing through narrow tunnels, we look for traces of uranium and signs of radiation behind each corner. That’s nonsense, of course, but it’s easy to let our imaginations run wild here, where our unease is magnified by the deep shaft and quarter-mile-long tunnel between us and daylight.

EPILOGUE

Once again we hear the rumbling and the sound of water dripping into the pool at the top of the shaft, but now it comes as a liberation — taking our first breath of musty mine air marks a return to the realm of the living. The black walls no longer seem that scary. The rumbling is only the modern ventilation system. The water does not feel as cold, and the Soviet bomb is just a replica. But the story of the miners of Podgorze and the yellow train is real, and one we won’t soon forget.

Martin StrmiskaWork gear left in the mine.

Need to Know

When to Go: Water temps are a stable 52°F throughout the year. During heavy rains, visibility can drop slightly. Winter brings a gloom that emphasizes the creepy nature of this dive; in summer, the weather makes the overall experience easier.

Getting There: Prague, Dresden (Germany) and Wrocław (Poland) are the closest international airports. Renting a car at the Prague airport and driving about 100 miles across the Great Mountains is the best option.

Operator: Filip Długosz is responsible for diving activities. All dives are guided cave dives. Full cave certification is required, as well as dive insurance.

Price Tag: Two dives costs about $160 USD per diver.

Where to Stay: Jelenia Gora, a small town about 12 miles north of the mine, provides comfortable accommodations at reasonable prices. Snežka, in the Great Mountains, is a popular ski resort; rooms here are more expensive and in demand, so book months in advance.

Martin StrmiskaA view of the vertical shaft from the surface (left); the end train station.

Tips for Shooting a Mine

1) Use an external light source. When shooting in a cave or mine, use as little of the camera’s onboard strobe as possible. Capturing attractive images with a pleasing 3D effect requires an external light source. The more the on-camera strobes are used, the flatter the image will be.

2) Bump up the ISO on your camera. You want to use as much of the available external light as possible.

3) Great buoyancy is critical. Mine tunnels are low and narrow. At the bottom, there is a layer of super-fine sediment that can screw up a photo shoot before it even starts.

4) Shoot what is unique to the setting. The wooden walls and shaft make Podgorze special, so focus on these structures. Apply this logic wherever you are shooting.