What Do Fluorescent Night Diving and Underwater Vehicles Have In Common?

Kevin RaskoffThe glowing underwater creatures you see night diving in Hawaii and Tahiti could change the design of future underwater jet-propulsion vehicles.

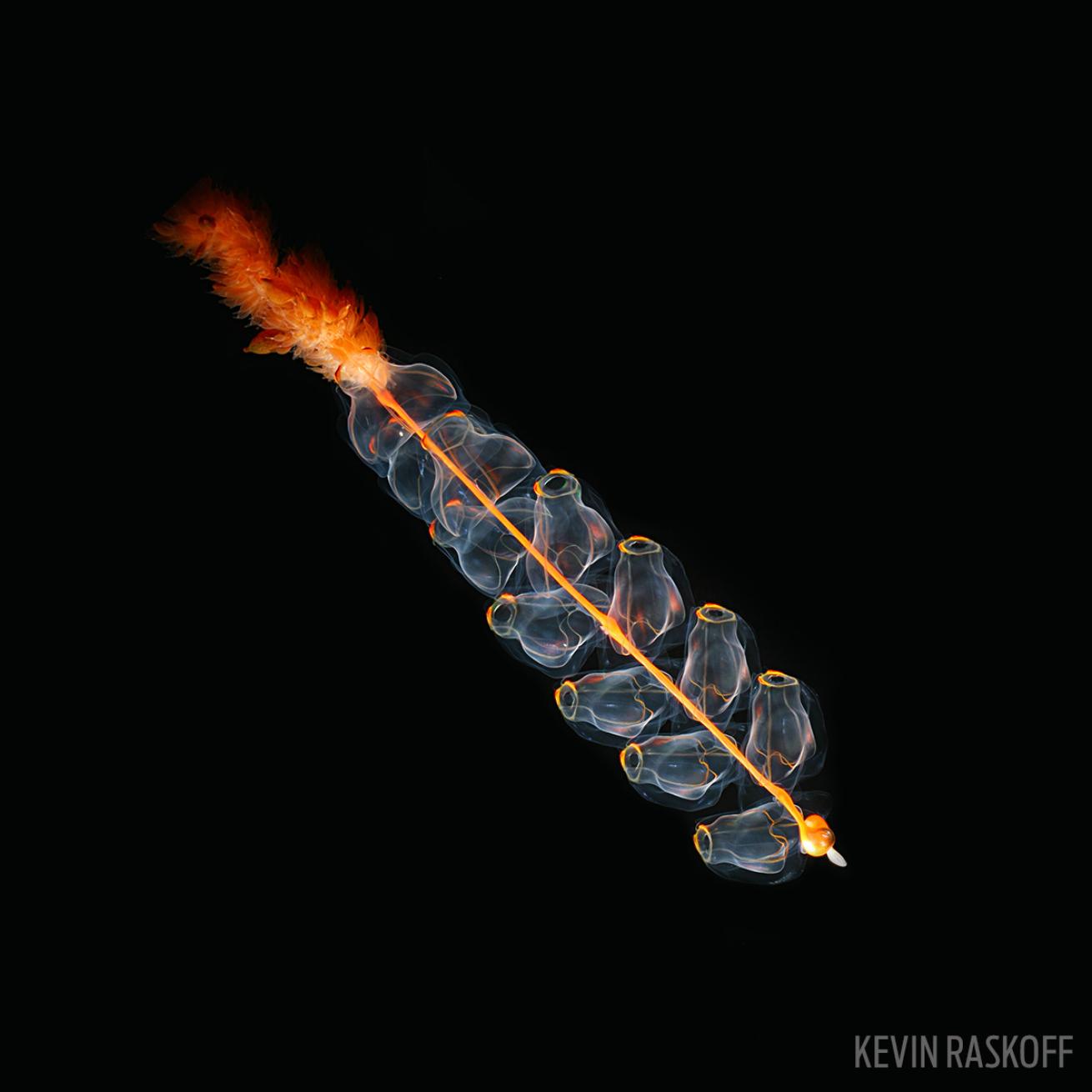

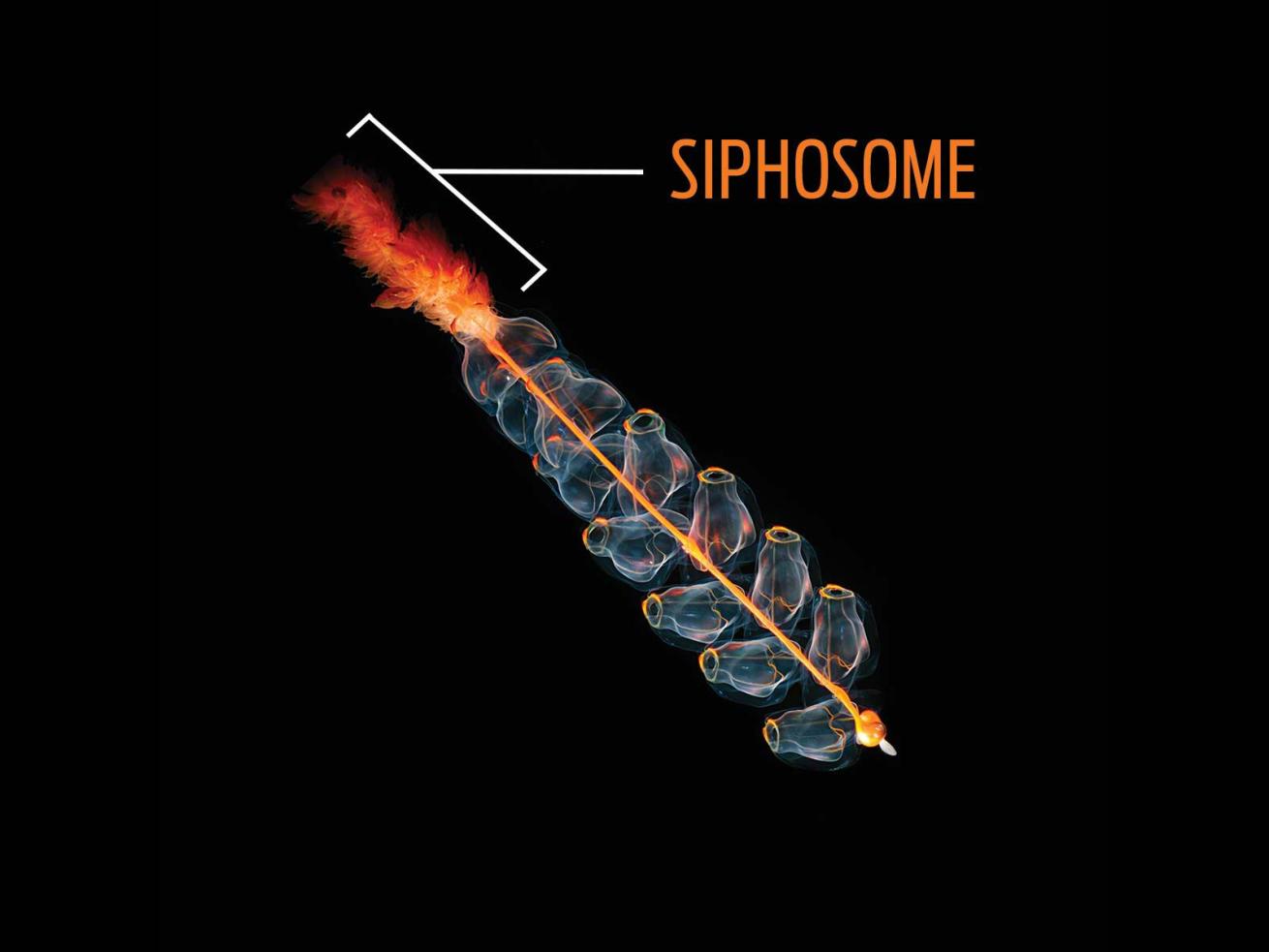

If you’ve dived the open ocean off Hawaii or Tahiti at night, you’ve probably seen it: a glowing, segmented line that appears to be a single animal but really is many animals working together, collectively known as siphonophores. Now scientists are going beyond the startling beauty of these “multi-engine organizations” and investigating whether their unique method of propulsion could change how we design undersea craft for future generations.

“We can perhaps peer into our own future in the sea,” says marine biologist Jack Costello of Providence College, one of the researchers, “by studying how this seemingly simple animal jets from one part of the ocean to another, relying on its youngest crew members.” (Star Trek fans, score one for Mr. Chekov.)

Lots of marine animals move by jet propulsion — squid and jellyfish spring to mind— but siphonophores are uncommon in that they represent an entire colony that is coordinating individual jets to move the collective as a whole, something like the way each crew member aboard the Starship Enterprise has a specific role in guiding the ship.

In a study published in the journal Nature Communications, Costello and colleagues from Roger Williams University in Rhode Island, the University of South Florida, Stanford University and the University of Oregon examined a siphonophore known as Nanomia bijuga. The group of researchers found that younger and older colony members fulfill distinctly different functions.

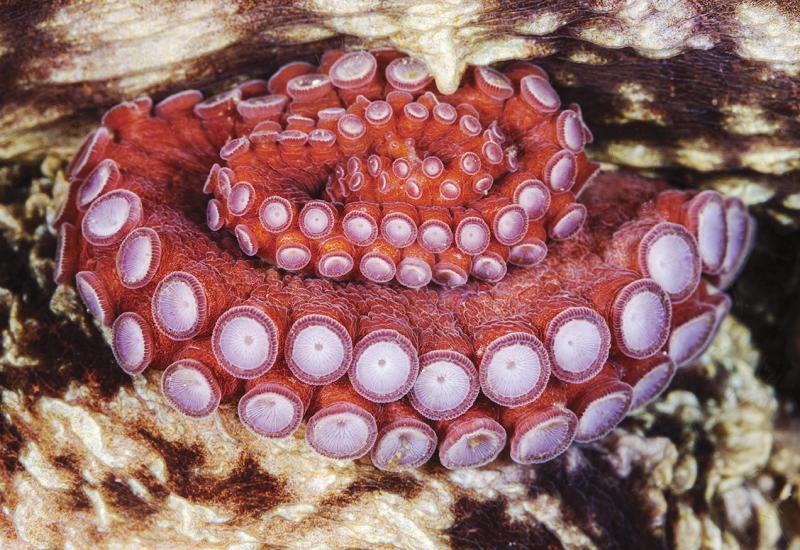

N. bijuga belongs to a group of colonial animals called physonect siphonophores that are related to jellyfish, anemones and corals. These plankton-feeders rise to the surface of the world’s oceans at night to hunt, then return to the depths by day to avoid being hunted themselves.

Costello explains that younger, weaker members, located at the front of the organism, are responsible for turning and steering. Older — and larger — members at the rear provide more thrust. “It’s a sophisticated design in what would initially seem like a simple organism,” Costello says.

The findings suggest it might be possible to design an undersea vehicle that, like N. bijuga, twirls as it moves, propelled by front-to-back thrusters, “a natural solution to multi-engine organization that might contribute to the expanding field of underwater-distributed propulsion-vehicle design,” the study concludes.

Kevin RaskoffGlowing Underwater Creatures

The jet-propulsion members of a siphonophore colony are called nectophores, and they are genetically identical clones arranged in what's known as a nectosome.

Kevin RaskoffGlowing Underwater Creatures Night Diving

The jet-propulsion members of a siphonophore colony are called nectophores, and they are genetically identical clones arranged in what's known as a nectosome.

Kevin RaskoffGlowing Underwater Creatures Night Diving

The nectosome is only a few inches long, but it tows much longer groups of reproductive and feeding units across distances that can reach 650 feet or more per day — the human equivalent of running a marathon every day.

Kevin RaskoffSiphonophore night diving

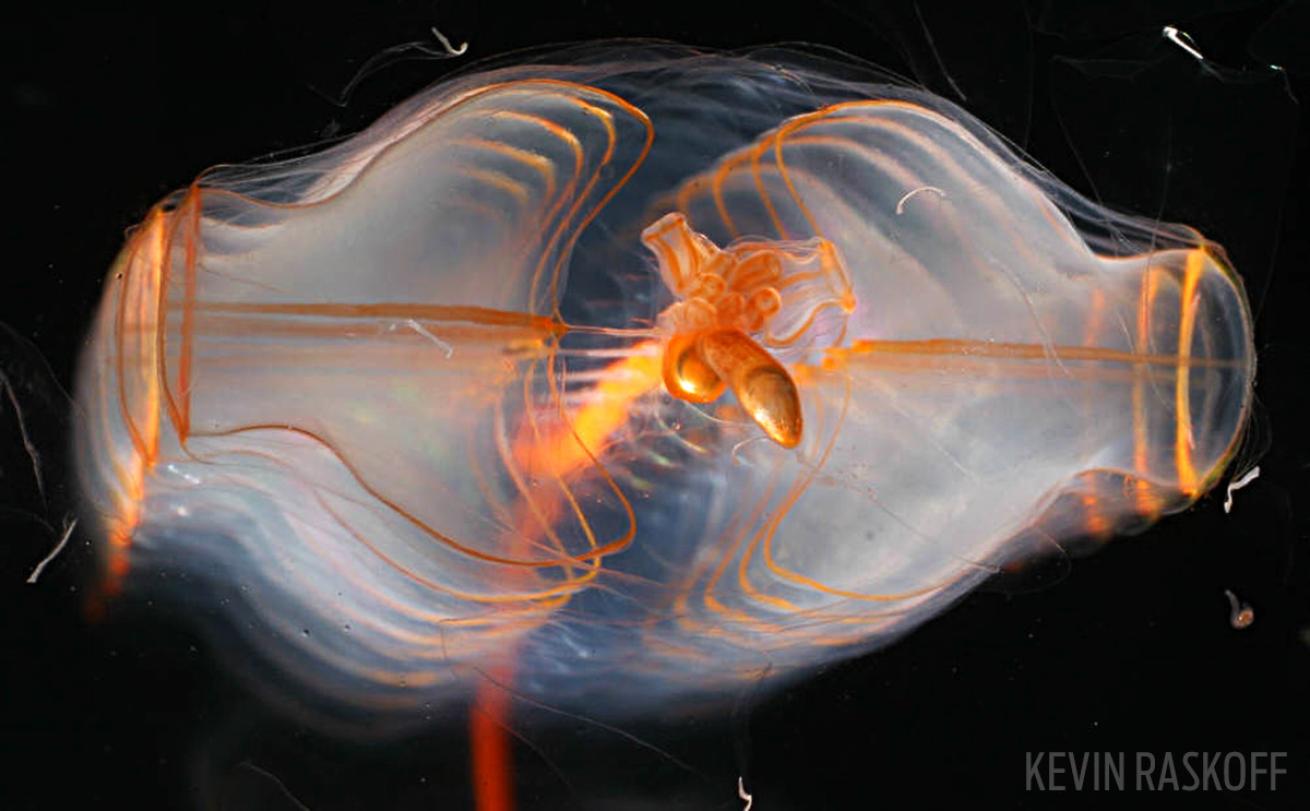

A nectophore budding zone is where a siphonophore’s swimming areas are made.