Dangerous Diving Jobs

The hazardous career field of commercial diving was once largely defined by the deep-water saturation divers working the oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico and the North Sea. But saturation diving isn't the only dangerous diving job around. Someone has to dive the 150-foot-tall water towers on the blizzard-blown Kansas prairies where it's gravity, not gas saturation, that will kill you. Someone needs to slip quietly inside the tangled gloom of a tuna net to check on great white sharks. Someone needs to make sure those scientists chasing penguins under the Antarctic ice cap don't drift away from the hole. And yes, someone has to dive inside nuclear reactors. (But hey, we hear the tan you get is just fabulous.)

So who are these people, how did they get into it, and most important, what are they doing under there?

Water Supply Diver

Over the years, Chad Campbell has taken a lot of good-natured ribbing from his buddies in the offshore dive world. The 39-year-old director of safety and training for Liquid Engineering oversees a team of 20 potable water supply divers. His company has nationwide contracts to inspect, clean and maintain drinking water tanks and towers in the 48 contiguous states. If that sounds easy, then Campbell, a 1996 graduate of the Divers Institute of Technology in Seattle, has news for you.

"I get calls all the time from guys who say, 'Hey, I'm a rock climber,' or 'I've been a roofer, heights don't bother me.' But let me tell you, there's a hell of a big difference between being 30 feet up on a rock face or roof, and being 150 feet on top of a round tower that is swaying in the wind." Being a diver isn't enough, he says, "you've also got to be a mountaineer."

To access their dive sites, Campbell and his three-man crews go up the built-in ladder systems and then use technical climbing gear-harnesses, ropes, pulleys-to hoist their dive gear to the top. They wear specially designed dry suits to avoid contaminating the water, and breathe off umbilical cords managed by a tender. Just entering the tanks can be tricky, Campbell says. "Some of these hatches are barely two feet in diameter."

Deep inside the big tanks it can be pitch-dark and often very cold. "I dove a tank one winter in Cody, Wyoming," Campbell remembers. "It had a three-inch ice cap." Getting trapped is a constant worry. "Often these tanks are in full operation with water being pushed in and out. Differential pressure is something we're very concerned about." Approach intake plumbing that's lost its screen, and you can find yourself on the wrong side of a body recovery operation.

Not surprisingly, Campbell's outfit has seen tragedy. In 2002, one of his divers was climbing a tower in Kansas. "Of the thousands of ladder rungs that all my divers have touched over the years, he happened to grab the one bad one that had rusted through," Campbell remembers. The rung popped off in his hand 55 feet above the ground. While OSHA cleared the company and praised their safety measures, none of that mattered much to Campbell. "He was only 27," he says of his friend. "He had three kids."

And for those Gulf divers? "I had one up not too long ago. He told me he wanted to 'take a break from the tough stuff and do some easy inland diving.' He went up a tower and when I didn't hear from him in awhile, I went up after him." The man was frozen in fear. "He turned to me and said, 'If any of my buddies tell me what a wuss I was for coming inland, I'm going to punch them in the face. This is as hairy as anything I've done in the Gulf.' "

Polar Ice Safety Diver

For a moment, Rob Robbins, supervisor of dive services with Raytheon Polar Services, had a sinking feeling he was about to participate in a double fatality under the Antarctic ice. He had enough air to make it to the main entry hole in the ice cap, but the scientist diving with him didn't. Her tank was almost empty, and she was pinned to the underside of the ice in her over-inflated dry suit, missing a glove, and giving him a confused, "what's up?" shrug. He dropped his brand-new underwater camera, desperately hauled her to a nearby safety hole where he managed to stuff her feet-first into the hands of topside tenders. She was clueless at her close call, Robbins remembers. "We got out and she said, 'Wow! What a wonderful dive!' "

Rescue work, albeit not in the Antarctic waters, is how Robbins got his start in diving. After graduating from high school in southwest Oregon, the teenager headed to Johnston Atoll, where his father, a military contractor, helped him land a job as a lifeguard at the base swimming pool. The warm South Pacific and Lloyd Bridges' Sea Hunt lured him to scuba. Within five years he was back in the states, a freshly minted graduate of the Florida Institute of Technology's commercial dive program.

In August 1979, Robbins stepped out of a U.S. Navy C-130 onto a crunchy ice runway at McMurdo Base, never having made a single ice dive. Now, almost 30 years and 1,458 Antarctic dives later, he's the venerated father of Antarctic ice diving.

Roughly 20 scientists, whose dive projects have been approved by the National Science Foundation, show up on the last continent every year. "We've had scientists trying to figure out why fish don't freeze when the water is below freezing, studying penguin physiology, and even working with sea urchins," he says. His job is to keep them alive through training and in-water support, something that's not an easy task given that scientific divers often only meet the barest minimum requirements-certified for one year, have 50 logged dives, 15 in a dry suit, and 10 of those within the past year.

The cold, of course, is the first challenge. With water temps at 28.5F, regulators can freeze and free flow, so divers use two. "We train them how to take one regulator out of their mouth and put another one in," he says. "It's amazing how hard it is to find your mouth when your face is frozen."

They dive under ice eight to 20 feet thick, an overhead environment where the key to surviving is always knowing where the entry/exit hole is. "The visibility is so incredible under the ice when the sun is out, sometimes as much as 800 feet, that we don't dive tethered. Instead, we have a drop line with flags and strobes." The same visibility that makes it easy to find the hole is also distracting. "You see whole landscapes under there, ranges of hills, valleys." The visual wonderland is seductive. "I've briefly lost sight of the hole three times," he says. "And let me tell you, it's a very, very bad feeling."

The chamber at McMurdo has treated six divers over the years. It couldn't save the sole American casualty, however, a diver who embolized after using his dry suit as a lift bag to move a piece of steel. "He dropped the steel and shot to the surface," Robbins says. "He was expired when we got him out of the hole." There are biological threats, too. In 2003, a leopard seal claimed a scientist at the British Rothera Research Station near Palmer. "She was snorkeling, but she had a dive computer on, so we know a little about what happened. The seal grabbed her and took her down over 200 feet. She died by drowning, and probably other injuries." They're big, aggressive and spooky-looking predators, he says. "When they show up, we leave the water."

Despite the dangers and the cold, Robbins finds himself returning season after season. "People ask me, where's the best diving I've ever done? Truk Lagoon? The Red Sea? I always tell them McMurdo," he says. "I love the stark contrast. Above the ice there is nothing alive, it's just blue and white. But you drop through that hole and suddenly the world opens up in vibrant, lush colors-deep red starfish, pink soft coral. There's no place else like it in the world."

Shark Wrangler

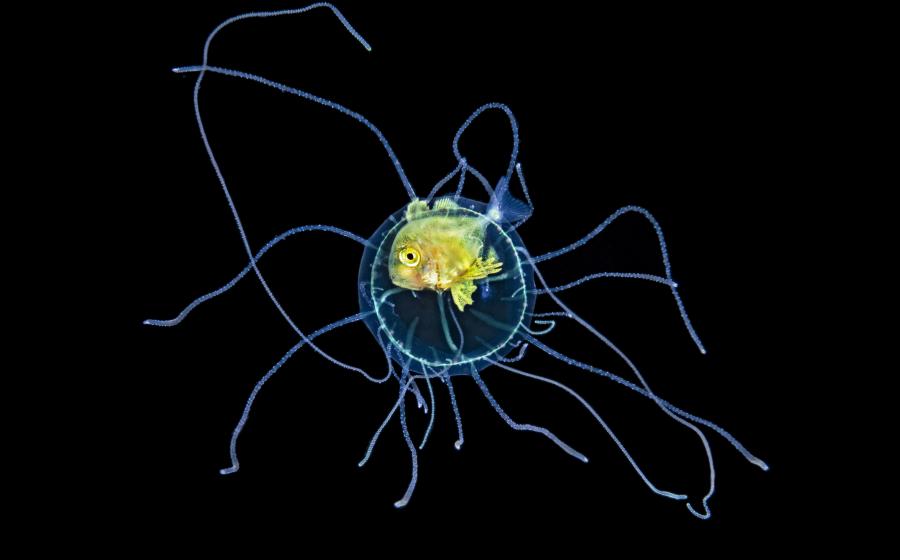

Almost every day during the hot California summer, Gil Falcone, a 41-year-old senior dive safety officer at the Monterey Bay Aquarium, motors out to a tuna pen in the warm shallows off Malibu. A nylon net made up of two-inch squares encloses four million gallons of the murky green water. The bottom is anchored and the top is held open by floats and a series of surface lines, but the net is flexible and morphs into different shapes in the strong currents.

There's also a three-foot-high fence around the top to keep hungry sea lions from raiding the net. But any sea lions that jump this net would be in for a big surprise. Instead of tuna, the enclosure holds a great white shark. The aquarium, a leader in promoting the conservation of these apex predators, has used the pen since starting the program in 2002 to hold juvenile sharks caught by local fishermen. Two of these were later exhibited for the public at the aquarium before being released to the wild again.

Falcone's job is to dive deep inside the murky pen, tie off chunks of mackerel and salmon for the sharks, observe their behavior and judge their health. He does this without using a cage or chain mail suit. His only protection, in fact, is a blunt piece of PVC pipe-"it helps steer the sharks away without hurting them"-and an electronic repelling device called a Shark Shield that Falcone says, "really doesn't seem to have any effect at all on the juvenile white sharks."

Falcone, who grew up in New Jersey and was certified in a rock quarry, developed a love for sea creatures while working on his marine biology degree at Colby College in Maine, and doing field research in the Virgin Islands. After a decade bouncing around the country between various research projects and collecting an impressive roster of instructor ratings, he began volunteering at the aquarium before being offered a full-time position. His job at the aquarium includes everything from working deep inside the pipes that feed and drain the tanks to doing light construction, but Falcone has a special affinity for diving with the white sharks.

Is he scared? "No, they fascinate me. You realize you are looking at something that is so much more highly evolved than we are in the water," he says. "You're down there in the green water, and they come out of the gloom to check you out, track you with their eyes. And even though they're a third the size of full-grown adults, they look just like them." And just like full-grown adults, they have the speed, and the crushing jaws rimmed with razored rows of teeth.

Could one kill him? He protests that the sharks aren't interested in attacking him at all; if anything, they're just curious. But when pushed, there's the stark reality: "They have a six-inch bite radius, so yes, they could kill you."

Of course, Falcone is the kind of guy who has a way of shrugging off the dangerous aspects of his job. Instead of life-or-death scenarios, he says he faces "interesting situations." One of those "interesting situations" happened recently while diving in the white shark net, though it had nothing to do with the animals.

"There was a strong current and suddenly I found myself caught in a pocket of the net." The nylon and cotton filaments surrounded him like a wet burial shroud; net above, below, net all around. Gil's training took over. He didn't panic and started hacking away. "I got my buddy's attention, and we worked our way out of the situation, swimming hard into the current." He made it safely out and cancelled the rest of the dive.

And if he ever encountered a white shark outside the net on a recreational dive? "I'd be thrilled to see one. I'd probably sit and appreciate the view," he says, pure joy in his voice. "And then I'd get out of the water."

Nuclear Reactor Diver

After nearly three decades, Charlie Vallance is used to the raised eyebrows and gasps of surprise he gets when people learn what he does for a living-diving inside nuclear reactors. "The typical reaction is, 'You dive where?'" says the general manager of technical services at Underwater Construction Corporation in Florida.

There are 104 nuclear power plants in the United States, and they all depend on water-lots and lots of water-to drive the turbines and create energy, to keep the reactor core from melting, and for emergency cooling in case of an accident. Some of the suppression pools contain more than a million gallons of water. "Most of these tanks are made of carbon steel, and we have to inspect and maintain them-maybe do the odd weld repair or replace the coating if it's starting to rust," Vallance says.

He began his atomic journey as a recreational scuba diver in 1965 and did some freelance commercial diving in college before joining the Marines. He eventually got his commercial diving certification and went on to work as director of the underwater technology program at the Florida Institute of Technology, before joining UCC to service nuke plants.

"In truth, it sounds a lot more exciting and dangerous than it really is," Vallance says. "Water is a very effective radiation shield. Just two feet gives you the equivalent protection of two to four inches of lead." Most of the areas the divers work in tend to be shallow, in the 10- to 15-foot range, but there is some deeper work in 40-foot pools or at the 80-foot levels near the bottoms of reactors. "Because water is such a good shield, you can actually dive inside the reactor vessel and work near spent fuel bundles."

But radiation can and does kill, so Vallance's divers wear multiple radiation badges on every dive and use a telemetry system that sends real-time readings to tenders. Each diver is limited to a cumulative radiation exposure of 1,000 millirems per year. To put things in perspective, the average U.S. citizen absorbs 200 millirems of radiation annually from naturally occurring radon gas, and gets a 50-millirem dose with every diagnostic x-ray.

When they dive uncontaminated water, Vallance says, their gear is pretty similar to what recreational divers use, except for the radiation sensors. Diving contaminated water is a different story. "We wear vulcanized rubber dry suits-helmet connected-and use positive-pressure, surface-supplied air." At the end of each dive, technicians wash down the divers and gear, check everything with meters, then wipe down everything with special pads that can check for contamination. The whole process can take up to half an hour. "This kind of diving takes a lot of patience," Vallance says. "A task which would take one day outside a plant can take a week on the inside."

Any fatalities? "I can't think of a single death of a diver working inside a nuclear power plant," Vallance says, "but I know of at least eight deaths from divers working outside the plants, in the intake pipes and turbines. Guys get drowned. Guys get crushed. That's where the real danger is."

Interested in a career in commercial diving? Check out Ocean Corporation