Can Magnets Keep Beaches Shark-Free?

Courtesy Craig O'ConnellA great white shark off the coast of Cape Cod.

Sharks are some of the ocean’s most attentive listeners. Of particular interest are low-frequency sounds, potentially signaling free lunch. When struggling, fish emit these low-pitched noises, slapping their tails and bodies about.

Sharks are also tuning into boaters' rock music. The low bass coming from the vessel sounds like a fish in distress.

Country, hip-hop, electronic—It all may spark curiosity in sharks, including great whites.

The good news, says Dr. Craig O’Connell, a shark behaviorist, is that “eventually the sharks get used to the music and swim off.”

But finding a correlation between music and sharks sparked the question: “If rock draws sharks in, might a different sound repel them?”

Related Reading: Finding Family-Friendly Diving in Fiji

That set O’Connell to work, in concert with Discovery’s Shark Week videographer Mark Rackley. Together off the coast of Chatham, a Massachusetts town on Cape Cod known as the Great White Capital of the World, they tested what happens when these sharks hear the vocalizations of orcas, one of the animal’s only predators.

“Sharks are generally very curious,” he says. “If they hear or smell something different, they often come in and check it out.” But when hearing the orca noises, they were anything but curious. They invariably swam away from the research boat.

“They showed a very vivid response,” he says. The sharks’ repulsion to the orca sounds is one more piece in the shark-repelling arsenal that O’Connell has been crafting for years. For O’Connell, this quest started after he completed his undergraduate studies at Boston University. Drawn to the ocean, he knew he wanted to help make the beaches safer for swimmers and sharks alike.

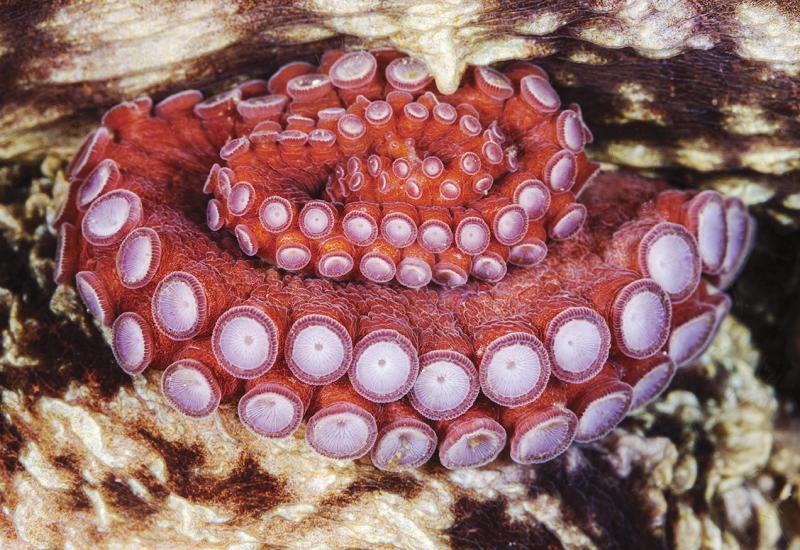

“It’s not appropriate to kill wildlife to make the ocean better for you recreationally,” he says. His early experiments back in 2006 took place after learning about magnetism and shark sensory biology at Boston University. Upon learning about sharks’ ampullae of Lorenzini—sense organs that detect electric fields—he started to wonder if a magnet stronger than the earth’s natural magnetic pull might deter sharks.

Courtesy Craig O'ConnellO'Connell working on the shark exclusion barrier in the murky waters of Cape Cod.

With that question, he applied to the Bimini Shark Lab in the Bahamas. There, he began testing his theory, exposing the local bull and tiger sharks to them. He found that they wouldn’t come near strong magnetic fields. In a more controlled experiment, he placed magnets along the diameter of a 30-foot shark pen containing juvenile lemons. Within 45 minutes, not a single shark crossed the barrier.

“It was the most mind-blowing thing I had seen,” he says. “That is what accelerated this work.” He then tested magnets with tiger sharks, finding the same result. Better still, further tests showed that magnets don’t upset other fish or turtles. Over the years, O’Connell continued to tinker with and improve his designs.

In September 2023, along with Rackley, he deployed a large section of telescoping and electromagnetic PVC pipes, finding that the system spooked sharks. Not a single great white swam through. After two decades of testing, O’Connell is putting all the elements together, taking his latest shark exclusion barrier prototype to start testing at a remote Cape Cod beach location closed to public use.

The current model is massive—easily several football fields long. O’Connell is attempting to create an exclusion zone, that is safe for swimmers, but that sharks won’t pass into. The perimeter features three rows of PVC pipes staggered one yard apart. They reach from the seafloor to the surface.

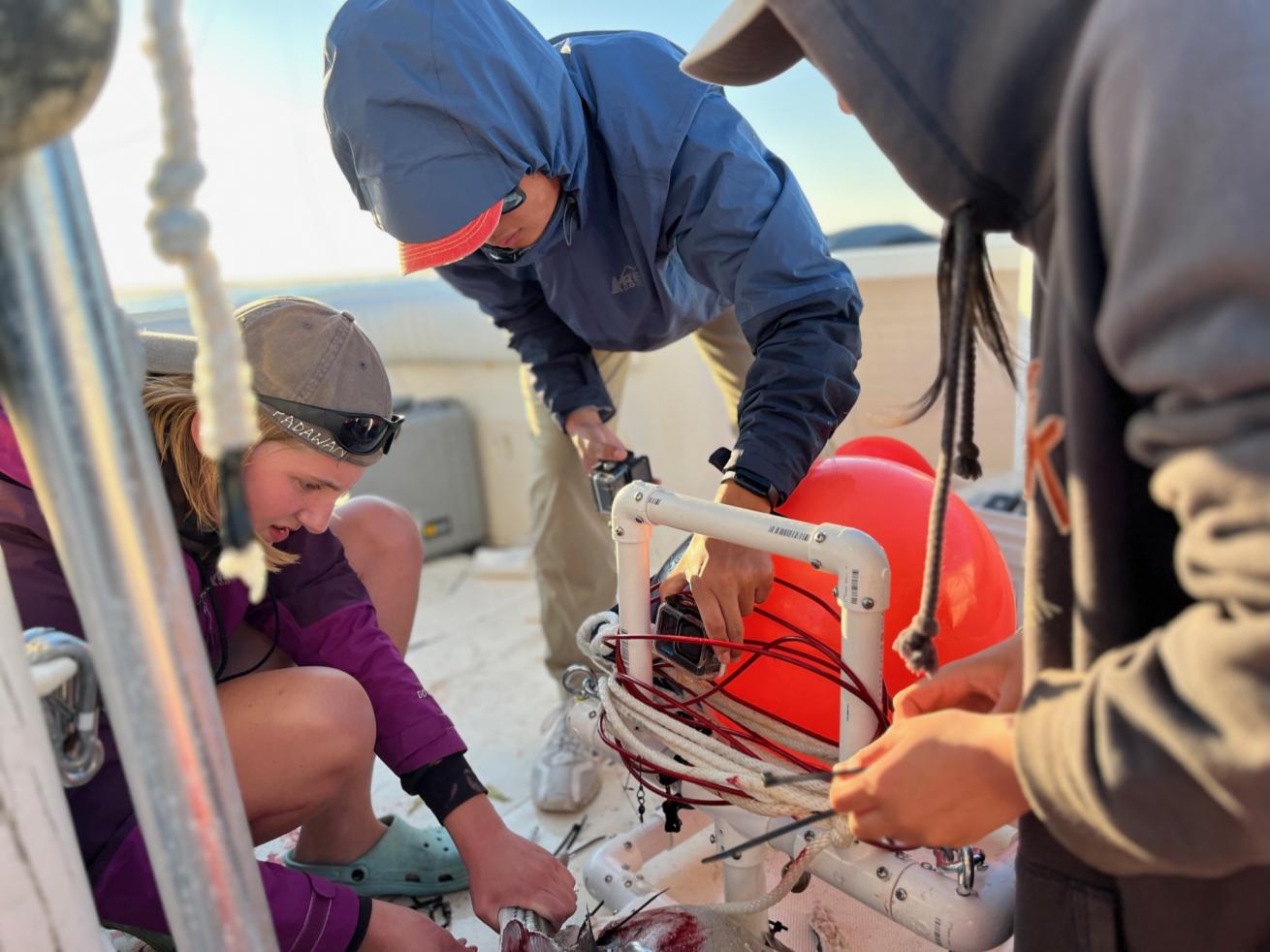

Courtesy Craig O'ConnellDr. Craig O'Connell's students design and build their own baited remote underwater video systems (BRUVS) to conduct remote surveillance of the Shark Exclusion Barrier in Chatham, Cape Cod.

Together, they create a visual barrier. Each PVC pipe also suspends electromagnetic devices in the water column, increasing the zones’ effectiveness in deterring white sharks. “The electromagnets are enormous—the size of a clay brick that you’d use in landscaping,” he says.

Their first test took place in October 2024, and the results will be available to the public soon. October is a prime month to test for two reasons. It’s the peak season for sharks. “Everything aligns,” he says. “There’s an abundance of prey, so the sharks beef up on food before heading to South Carolina and Florida.”October is also past the tourist season. The testing will occur at a beach far from public areas, but it helps to conduct research without people potentially swimming out to check out the barrier.

Related Reading: Swimming With Whale and Basking Sharks

Courtesy Craig O'ConnellDr. Craig O'Connell of the O'Seas Conservation Foundation readies for in-water observation of the sharks.

“We’re trying to keep it away from people until it has been effectively tested,” he says. In a few months, O’Connell and his team will know more. For now, the testing is focusing on electromagnetic devices with the visual barrier so as to accurately gauge effectiveness. Orca vocalizations won’t be used at this stage. To make sure they know what is or isn't working, the team has to keep the two deterrents separate during the experimentation phase.

“We’re hoping this is the solution,” he says. “Only time will tell.”

Dr. Craig O’Connell is a shark researcher and the founder of the O’Seas Conservation Foundation, a Montauk-based nonprofit dedicated to conducting pioneering shark research and teaching kids about shark conservation.