13 Facts You Didn't Know About the Marine Iguana

Isolation in the Galapagos Islands helped shape these deep-diving reptilian marvels

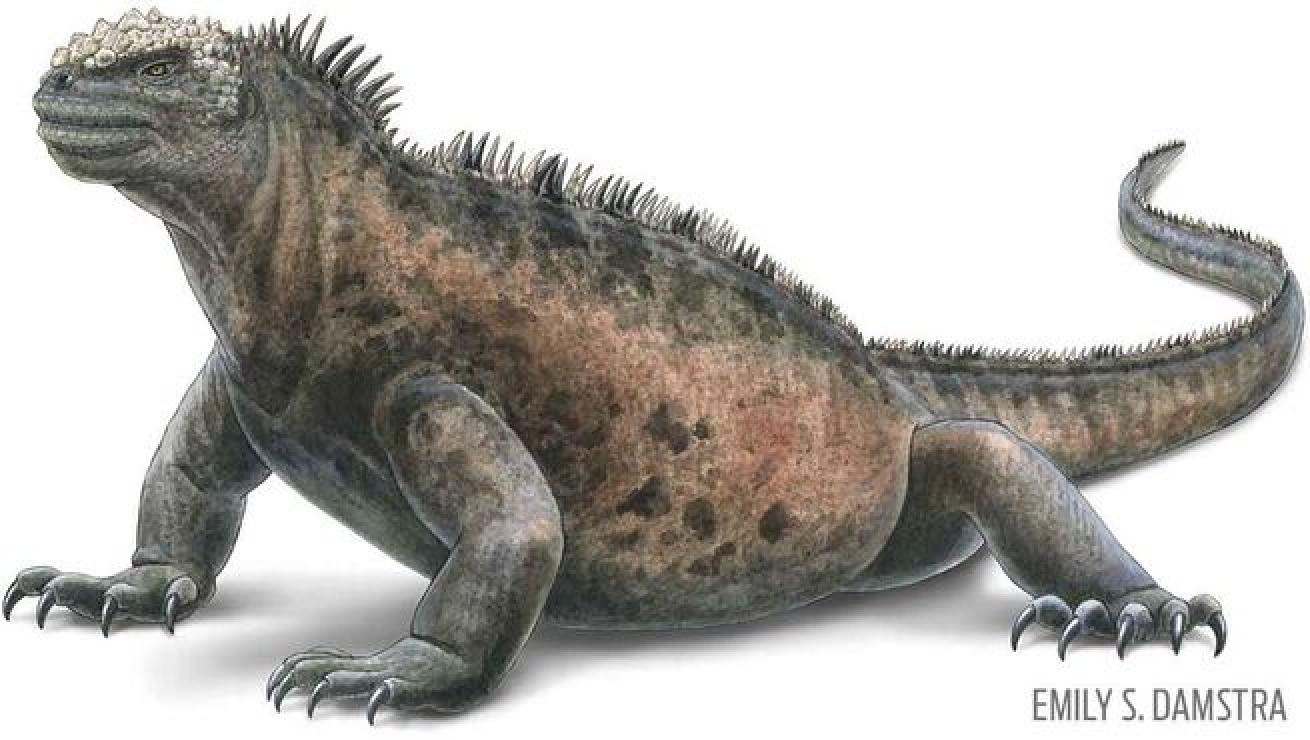

Illustration by Emily S. DamstraThe marine iguana

The marine iguana is found only in the Galapagos Islands.

As a result of El Niño, pollution and the introduction of nonnative species, the marine iguana is considered vulnerable to extinction.

iStockphotoMarine iguanas feed exclusively on marine algae

Marine iguanas feed exclusively on marine algae, a unique trait among lizards.

Charles Darwin was revolted by their appearance, writing they are “disgusting, clumsy lizards.”

Related Reading: 3 Nearshore Habitats to Dive

Amblyrhynchus cristatus can reach 26 pounds in weight, which is equivalent to an average 18-month-old child.

These marine reptiles encountered terrestrial predators for the first time about 150 years ago. Introduced dogs have reduced their population by a third in some areas.

iStockphotoThe Galapagos hawk is a natural predator of the marine iguana

The marine iguana’s only natural predators are Galapagos hawks and certain herons, which feed on young iguanas.

The marine iguana removes excess salt from its body through glands in the nose. It excretes salt by squirting it several feet out of its nostrils.

Related Reading: 6 Animal Encounters to Add to Your Bucket List

El Niño greatly reduces algal growth and can cause widespread starvation in marine iguanas, killing up to 85 percent of individuals in some cases.

These graceful swimmers can dive to 65 feet, deeper than permitted for a PADI-certified Open Water Diver.

Westend61GMBH/AlamyMarine iguanas on the Galapagos islands

The males sometimes swim between islands to mate, which explains why there is just one species of marine iguana compared with a dozen Galapagos giant tortoises isolated on different Galapagos islands.

The female marine iguana is receptive to mate for just three weeks per year. It lays one to four eggs, which take 100 days to hatch.

During a mating period, the male marine iguana can fast for two weeks in order to maintain its territory, a period of time in which it can lose a quarter of its body weight. Some males — typically black or gray — also turn shades of red and green around mating season.

Follow Richard Smith’s under water adventures at oceanrealmimages.com.