Roatan Aggressor Crew Reveal Why They Live "The Dive Life"

Mary Frances EmmonsStaff dive instructors Willie Waterhouse, left, and Gabi Ruben aboard Roatan Aggressor.

Nine-year-old Willie Waterhouse lay in the bottom of his family’s dugout canoe, retching himself dry. His uncle had reluctantly taken him out again, despite the boy’s debilitating seasickness. Willie’s dad, a Utila boat captain, told him if he wanted a life on the sea, he would have to work through it. “I was determined,” Waterhouse says today with a smile.

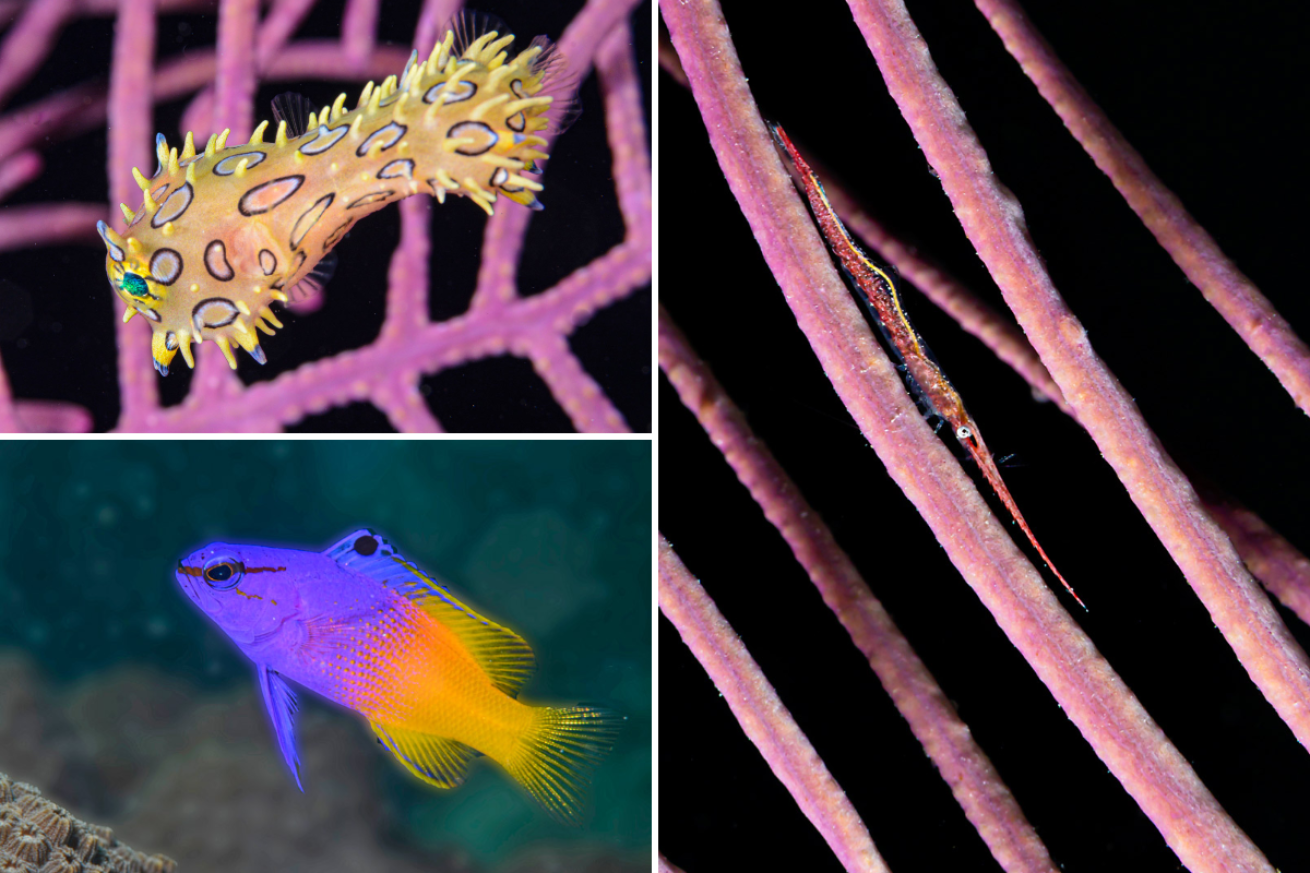

Flash forward a couple of decades. A giant of a man, Waterhouse has a knack for spotting the tiniest of Roatan’s startling array of macro life. A PADI Instructor aboard Roatan Aggressor, he shows us camouflaged neck crabs, baby mushroom scorpionfish, bizarre spongy decorator crabs—things we didn’t even know existed.

“I love finding new creatures,” he says. “Anything new blows my mind.”

Over the Drop We Go

Finning over the magnificent, hundred-foot wall that more or less rings the largest of Honduras’ Bay Islands offers all the thrill of jumping from a low-flying plane with none of the consequences. And no skydiver can level off and continue to explore—in any direction—the way divers can.

The first thing that draws the eye here is the sponge life, especially Roatan’s many great barrel sponges. Lest you think sponges do not excite, a few facts: Barrel sponges are animals, and unique in that they do not appear to react to contact with other species (as far as we can tell). Barrel sponges 3 to 4 feet tall are thought to be as old as 100 to 200 years, and some may be as old as 2,000 years, making them one of the longest-lived animals on Earth.

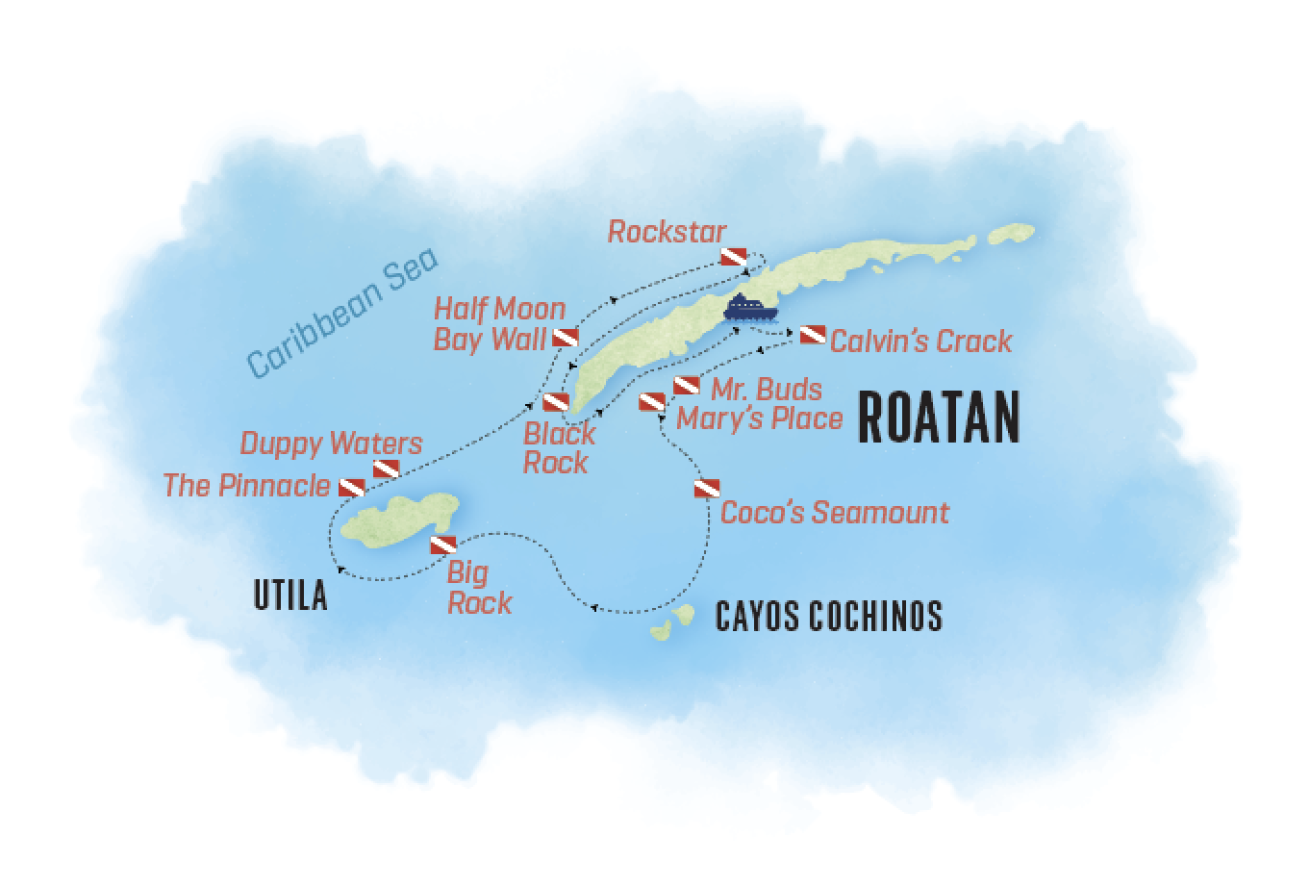

Roatan and especially Utila have barrel sponges twice that size—a 9-footer at Utila’s Duppy Waters site is one of the largest ever recorded.

As we motor along at about 60 feet at Blue Channel, off Roatan’s northwest shore, we look up to huge black grouper hovering at the top of the wall. They’re scaring the bejeebers out of clouds of bar jacks and creole wrasse, scattering schools like buckshot. It’s hard to tell if they’re hunting or, like us, just having fun. All up and down the wall, busy cleaning stations form perfect little tableaux. Gorgonians are everywhere, the gentle surge creating the impression that the entire wall is waving at us.

Image Courtesy of Aggressor AdventuresThe 110-foot Roatan Aggressor accommodates up to 18 divers on itineraries in Honduras' Bay Islands.

The Ocean is Calling

While the ocean is what draws divers to liveaboards, little has more influence on their experience than the crew, which typically numbers around one for every two guests on Aggressor yachts. No one has more impact than the in-water staff, who on Aggressor yachts must be certified instructors. In just a week, “you can give them memories and experiences they’ll never forget—and they’ll have a part of you in their hearts forever,” Waterhouse says. “That brings me joy.”

The path to becoming a dive pro is as varied as the divers who choose it. Growing up on nearby Utila, Waterhouse worked school vacations at a local dive resort, running compressors and being a general handyman. Eventually, he followed in his dad’s foot steps and became a captain.

But tourism can be an unpredictable way to make a living on a small island. Waterhouse noticed that while some captains were high and dry when guests were few, divemasters almost always had work.

He decided to go pro, and “that’s when I really got hooked,” he says. The ocean became his passion.

It’s a life that’s not without cost, missing many milestone moments with his family. But he’s passed that love on to the next generation—his youngest is “just like me,” he says, determined to get past his own seasickness and learn more about the world below. “It’s an amazing career,” he says, “unlike any other job out there.

Cockwise from top left: Martin Strimiska; Michelle Drevlow; Francesca Diaco;Clockwise from top left: A sponge shrimp at the dive site White Hole off Roatan's northwestern side; a yellowhead jawfish peeks out from some rubble on a sandy bottom; a tiger grouper pokes out of a giant barrel sponge at Spooky Channel on the northwest side of Roatan.

On the Wings of a Butterfly

It’s Easter week, in Central America an important time for being with friends and family, and many of the divers and crew aboard are beginning to feel like both. Plus, we’re hunting for eggs! (Jawfish, that is.)

At lovely, relaxing Half Moon Bay Wall I find eight adorable yellowhead jawfish popping in and out of their sandy burrows, but no eggs. It’s tempting to hunker down on the crystal-white bottom and watch the parade, but instead, I follow my own kind to a nifty 25-foot-long swim-through that deposits us on the deep-blue side of the drop at around 70 feet. (A few days later at Spooky Channel we are rewarded with a mottled jawfish incubating eggs in his open mouth, their silvery reflection turning him into a tiny, toothy Bond villain.)

Back at Half Moon Bay we descend again under a nearly full moon for a night dive with Waterhouse. Almost immediately, huge channel clinging crabs are everywhere, male and female, all on the move. I quickly find a sinuous Caribbean reef octopus, and Waterhouse spots another, the first of four—four!—we see that night, the most I’ve seen on one dive. We round out the evening with mantis shrimp, camouflaged crabs and nudis so tiny I can barely make them out.

As we ascend at last, Waterhouse has something in his lights. A squid? But it’s something much rarer: a fluttering, diaphanous sea butterfly—a type of swimming snail even Waterhouse hasn’t seen before—and we linger as long as we can.

Back on the boat we’re elated; no one can stop laughing and talking, mostly all at once. (The splash of Flor de Caña rum in our post-dive hot chocolate doesn’t hurt either.) This is what we came for.

From left: Francesca Diaco; Martin StrimiskaA school of sergeant majors swims over the reef. Right: A green sea turtle at Calvin's Crack.

Something Was Missing

Instructor Gabi Ruben arrived at the dive life by a completely different route from Waterhouse.

Growing up in Birmingham, in England’s land-locked center, she was drawn to the water, spending her summers in the south with friends who surfed and dived. At 24 she was certified in Australia and spent years working and traveling in the region. An event coordinator by training, she eventually returned to England and the posh life, working with entertainment agencies to stage high-profile affairs. There was plenty of money, but “it was an unrealistic lifestyle,” she says. “Something was missing.”

Eventually, she escaped to a Seychelles marine conservation base where she learned to lay transect lines, collected underwater survey data, measured tortoises and sampled mangrove pH levels. She became a divemaster because the base housed volunteers “and I had to look after them,” she says.

She loved it, but eventually her savings began to run out. So she headed for Utila to continue her training, leaving as a PADI Staff Instructor. Teaching in Grand Cayman, she met the crew of Cayman Aggressor. She stayed in touch and eventually joined the company, working on yachts in the Bahamas, Turks and Caicos, and Belize. Today she’s the second captain and operations manager of Roatan Aggressor, where her job touches everything that happens on the yacht—she seems to be everywhere all at once, from before dawn till long after dusk. She still finds time to teach, mostly Enriched Air (Nitrox) Diver and Advanced Open Water Diver. “I love teaching Peak Performance Buoyancy,” she says. “It’s dramatic how you can change the way people dive in just one week.”

Claudio Contreras KoobColonies of elkhorn coral cover a reef at Cordelia Banks.

Rocky Mountain High

It’s unusually windy this cruise, and the crew works hard to keep us diving, experiencing some of Roatan’s best west- and north-side sites. On our second day the winds abate, giving us a narrow window of opportunity. The captain decides it’s enough to take a run at an open-ocean seamount that rises to within 45 feet of the surface about 19 miles off the southwest point of Roatan. It’s not far from sparsely inhabited Cayos Cochinos, just north of the Honduras mainland.

We descend to a school of 75 or more Atlantic spadefish, their silver stripes catching the morning rays in bright contrast to a dark cloud of black durgon 50 strong. The seamount is an undersea garden teeming with fish life and stuffed with gorgonians including black coral in white, brown, green and tan. Sponges proliferate here too—branching and azure vase, netted barrel, and several types of rope and encrusting sponges in many hues. This is what the Caribbean looked like 10 years ago.

I meander along in the company of a friendly Nassau grouper, lost in happy thoughts, until Ruben taps me on the shoulder. She points up. One hundred-plus horse-eye jacks form and re-form in spirals above us, spinning lazily in the sun. Mesmerizing.

Susan MeldonianA neck crab clings to a coral branch at Melissa's Reef on the north side of Roatan.

This Lovely, Fragile Place

The elephant on the dive boat, of course, is the state of the coral. In the past 50 years, hard coral coverage in the Caribbean has declined from roughly 35 percent to around 15 percent. In Roatan, it’s more like 20 percent. Roatan boasts many magical creatures, but it’s still part of planet Earth, subject to all of the man-made stressors found elsewhere: coastal development, warming seas, proliferating algae, diseases that attack weakened coral. “My father told me stories of things I will never see,” Waterhouse says. “And I have seen things my kids won’t.”

Yet Roatan is blessed: Its glorious underwater terrain will be there for generations to come. It’s what lives on that substrate that is in need of love and care from every diver.

Stewardship of the ocean is something PADI dive pros take as a mission. “This isn’t my job, it’s my life,” Waterhouse says. “If I stopped diving tomorrow, I would still work to care for the ocean. Most of all, you have to love the reef—you can’t take it for granted.”

For Ruben, that mission includes educating guests about reef-safe sunscreen, having onboard competitions for underwater trash collection, and showing photographers, especially, why it’s important to be sensitive to the critters they are shooting.

Clockwise from top left: Susan Meldonian; Andrew Raak; Susan MeldonianClockwise from top left: A juvenile bridled burrfish; a tiny gorgonian toothpick shrimp perches on a soft coral; a fairy basslet adds a shock of color to the reef.

Stewardship will be even more important to the next generation, who must decide how they will shepherd Earth’s fragile, beautiful seas. Julia Haralson, a high-school junior from Atlanta, is among the millennial and Gen Z divers who make up half our group this week. She’s come aboard with her grandparents, who’ve taken her on dive boats since she was 4. She got her Junior Open Water Diver cert on her 10th birthday. A certified rescue diver, she’s working her way toward divemaster.

“Divers see more than the average person,” Haralson says. She wants to teach teens and young adults, to share the world she knows. Dive pros “have a different perspective and appreciation for what’s around us. A lot of people my age are very interested to do what I’m doing.”

Eventually, everyone’s least favorite moment arrives: our last dive. We plunge in at nearshore Black Rock, at the very tip of West Bay. A chunky 5-foot green moray flows along the reef ahead of us as we near the point, paced by a scrawled filefish with in-tensely blue markings the exact shade of the sea around us. We turn the dive and rise to run along a shallow mini wall plastered with colorful sponges.

Our final sight as we head for the yacht is a glowing stand of elkhorn coral—critically endangered world-wide but surprisingly common around Roatan—reaching for the sun, for life.

The ocean is calling. How will you answer?

Monica MedinaMap of dive sites dived on this trip. Subject to change.

Topside Attractions

Roatan Yacht Club

This charming, recently renovated inn is Roatan Aggressor’s home port. Enjoy the swimming pool, open-air bar, good Wi-Fi and friendly staff if you have time to kill before boarding, or come early and extend your island visit. DJs and live vocalists provide evening entertainment that complements outdoor dining on the club’s expansive hilltop veranda, with views that sweep across French Harbor. Learn more here.

Daniel Johnson's Monkey and Sloth Hangout

Fancy hanging with a sloth? How about a monkey on your head? Parrot on your pinkie? (Kidding—they’re surprisingly heavy.) This family-run sanctuary minutes from Roatan Yacht Club lets you interact with capuchin monkeys and giant macaws. And yes, you can also enjoy a warm, fuzzy cuddle with an actual sloth.

Roatan Island Brewing Co.

Just a short drive up forested slopes is Roatan Island Brewing Co., offering Caribbean-crafted ales, lagers and more. Relax at indoor or outdoor tables (or snag a hammock), or amuse yourself in the leafy gardens with foosball, ring toss or horseshoes. Order a flight to sample from nine locally made brews you can pair with burgers, brats, and regional and vegetarian options.

Need to Know

When to go

Year-round. Whale sharks can be seen around Utila in March and April.

Dive Conditions

Water temps range from the high 70s in January to the mid-80s in September. Currents are sometimes present but rarely a problem. Viz is frequently 100 feet or more.

What to Bring

Most divers are comfortable in a bathing suit and rash guard or a light exposure suit. Layers will let you adjust your cover age as needed. (Roatan is a marine park; gloves are not permitted.) Carrying a surface marker buoy in case you unexpectedly need to surface is always a good idea.

Suggested Training

If you’re not already nitrox certified or an advanced diver, consider getting your Enriched Air (Nitrox) Diver or Advanced Open Water Diver on the yacht. Peak Performance Buoyancy is also easily executed from the boat.

Getting There

Roatan Aggressor docks at the Roatan Yacht Club in French Harbor, about a 20-minute ride from Juan Manuel Gálvez International (RTB), Roatan’s airport. Aggressor Adventures can arrange a transfer in advance for $20 per person.

Operator

Aggressor Adventures operates Roatan Aggressor, which visits Roatan, Utila and Cayos Cochinos, weather permitting. The 110-foot yacht accommodates up to 18 divers in nine staterooms with private head and shower. Meals and snacks include regional specialties and American favorites; beer and wine is included.

Price

Staterooms start at $3,195 per person double occupancy, not including a $145 port/marine park fee and $150 fuel surcharge, paid on board in cash.