Lessons for Life: Solo Diver Never Resurfaces

Lessons for Life 6/13

Jori Bolton

Ted couldn’t find a dive buddy who liked to dive as he did, so he dived alone. That was fine with Ted — he didn’t like to depend on anyone else anyway. He told his friends that he thought exploring the insides of deep shipwrecks was a solo activity — the areas were too cramped for a buddy to be of much help.

Ted was making his third dive of the day, entering a shipwreck 200 feet below the surface. He loved the feeling of exploring a ship that had been hidden for years from human eyes. He loved the mystery of it, and tried to imagine what the men and women on board must have felt when the ship went down. He liked being alone with his thoughts too — right up until he realized he wasn’t sure how to get back to the surface.

THE DIVER

Ted had earned his dive certification 10 years previously, just before his 30th birthday. Since then, he had taken only one dive class, his Advanced Open Water certification. He continued to learn by talking with other divers and reading about advanced-diving techniques. Over the years, he had acquired the equipment and experience to dive the way he wanted.

He dived regularly, and his friends thought of him as a very experienced diver. He preferred to explore wrecks in the colder waters of the northeastern United States. There were a few wrecks he dived on a regular basis, getting to know the ins and outs of each. He often joked that he could find his way out of some of those wrecks blindfolded.

While Ted liked to talk about diving, he didn’t like to talk about health issues that caused him to take several prescription medications. Nor did Ted mention his medical conditions on the liability release the dive charter made him sign before they left the dock. He simply answered “no” on each of the questions.

THE DIVE

The wreck rested on its port side on the sand. Conditions were good — very little current, and visibility was good for the area, better than 30 feet. This was the first chance Ted had had to dive on this wreck. He gave the divemaster a copy of his dive plan with the time he expected to resurface. He had planned his descent, bottom time, ascent and decompression down to the last minute.

He was on his third dive of the day,all on the same wreck. The boat had anchored at the site. They didn’t make it to this dive site often, so they wanted all the divers to see the ship.

THE ACCIDENT

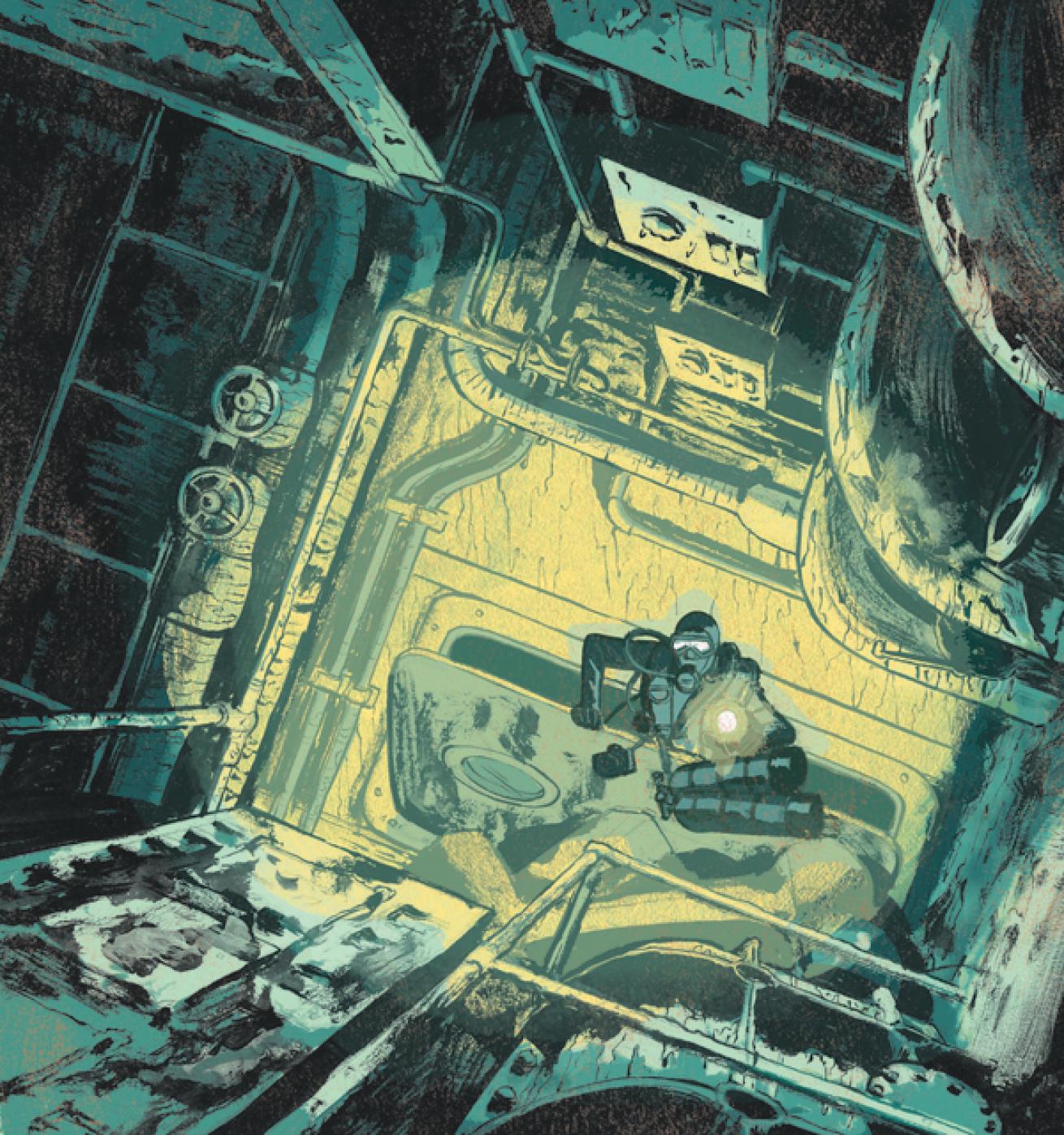

Everything was going according to schedule. On the first two dives, Ted had explored the ship’s galley and cargo holds. On the final dive, Ted planned to explore the engine room. The access door was partially blocked by equipment that broke loose when the ship went down. He wiggled through, pushing his equipment ahead of him. Because of the narrow opening and possible entanglements, Ted chose not to run a line inside the ship. He decided that the spaces would be tight enough that there was no way he could get lost. He was confident in his ability to find his way out. He was wrong.

The divemaster on the surface watched the clock carefully. He was surprised when Ted didn’t surface the exact minute he predicted he would. The divemaster continued checking buddy pairs back onto the boat and getting everyone settled for the hour-and-a-half boat ride back to the dock. When he realized Ted was 10 minutes late, he began to get worried. At 15 minutes, with none of the other divers reporting seeing Ted in the water or on the anchor line, the divemaster entered the water. He made a quick search descending along the anchor line all the way to the bottom. He looked around the exterior of the ship for about five minutes and then returned to the surface. Ted was nowhere to be found.

ANALYSIS

The other divers on the dive boat had each made three decompression dives that day. None of them could return to the water to search for Ted. Even if the divemaster hadn’t made a dive that day, he was alone and wouldn’t have been able to search the ship for the missing diver.

The boat captain radioed in an emergency, but the crew and rescue officials quickly realized they were in recovery mode. Ted still hadn’t resurfaced 30 minutes past his planned time. He had clearly run out of breathing gas. A rescue was out of the question.

Ted was diving alone. Even though he had a comprehensive dive plan, there was no one to lend assistance when he got in trouble. He had entered the shipwreck without securing a line to the outside. When he got inside the engine room and got turned around, he couldn’t find his way back out. It is likely that he stirred up silt accumulated inside the ship. While the visibility was relatively good on the dive, at 200 feet the available ambient light was minimal. As the day progressed toward evening, the sun’s beams hit the water at a more oblique angle, causing even less light to make it to the bottom. Even if he had turned his lights off and let his eyes adjust to the gloom, it is unlikely he would have been able to see light coming from the entrance. Ted was essentially making a night dive inside an overhead environment and was completely dependent on his lights. Without a guide line to follow, there was no way for him to escape.

Ted was taking a couple of different prescription medications, including Ritalin, codeine, antihistamines and benzodiazepines. Very little is known about the effect of pressure on medicine, so it is possible those drugs played a role. Another concern is the conditions that required Ted to use the medications in the first place. Without a complete medical history, we can only guess, but it is possible he had anxiety and attention deficit problems. If entrapment lead to panic, made worse by anxiety issues, he might have failed to think through the situation and work on his own escape.

Ted most likely suffocated when he ran out of gas. We can hope he lost consciousness before then. If not, he spent his last few minutes on earth watching his pressure gauge slide toward zero.

A general surgeon performed the autopsy on Ted and declared the cause of death an air embolism. Since Ted never ascended, that is unlikely. More likely, the long deep dives and accumulated nitrogen in his system led to postmortem bubbling in both arteries and veins. The bubbles likely accumulated in the heart, leading to that diagnosis.

Lessons for Life:

1. Solo diving is not for everyone. If you want to dive solo, seek additional training and be prepared to carry the necessary additional equipment.

2. Any time you enter an overhead environment, when you can’t make a direct ascent, attach a line to the outside so you can find your way back out.

3. Consult a dive physician about any medical issues you might have and the effects of the medications you take for them.

4. Be honest on your diving medical form. Discuss any conditions with a physician familiar with diving medicine.

5. For the dive charter: Develop a system to perform a search-and-rescue operation at any dive site before leading divers there. There should be at least two divers qualified to dive at those depths who haven't been diving that day.

Eric Douglas co-authored the book Scuba Diving Safety, and has written a series of dive-adventure novels and short stories. Check out his website at booksbyeric.com.

Jori Bolton

Ted couldn’t find a dive buddy who liked to dive as he did, so he dived alone. That was fine with Ted — he didn’t like to depend on anyone else anyway. He told his friends that he thought exploring the insides of deep shipwrecks was a solo activity — the areas were too cramped for a buddy to be of much help.

Ted was making his third dive of the day, entering a shipwreck 200 feet below the surface. He loved the feeling of exploring a ship that had been hidden for years from human eyes. He loved the mystery of it, and tried to imagine what the men and women on board must have felt when the ship went down. He liked being alone with his thoughts too — right up until he realized he wasn’t sure how to get back to the surface.

THE DIVER

Ted had earned his dive certification 10 years previously, just before his 30th birthday. Since then, he had taken only one dive class, his Advanced Open Water certification. He continued to learn by talking with other divers and reading about advanced-diving techniques. Over the years, he had acquired the equipment and experience to dive the way he wanted.

He dived regularly, and his friends thought of him as a very experienced diver. He preferred to explore wrecks in the colder waters of the northeastern United States. There were a few wrecks he dived on a regular basis, getting to know the ins and outs of each. He often joked that he could find his way out of some of those wrecks blindfolded.

While Ted liked to talk about diving, he didn’t like to talk about health issues that caused him to take several prescription medications. Nor did Ted mention his medical conditions on the liability release the dive charter made him sign before they left the dock. He simply answered “no” on each of the questions.

THE DIVE

The wreck rested on its port side on the sand. Conditions were good — very little current, and visibility was good for the area, better than 30 feet. This was the first chance Ted had had to dive on this wreck. He gave the divemaster a copy of his dive plan with the time he expected to resurface. He had planned his descent, bottom time, ascent and decompression down to the last minute.

He was on his third dive of the day,all on the same wreck. The boat had anchored at the site. They didn’t make it to this dive site often, so they wanted all the divers to see the ship.

THE ACCIDENT

Everything was going according to schedule. On the first two dives, Ted had explored the ship’s galley and cargo holds. On the final dive, Ted planned to explore the engine room. The access door was partially blocked by equipment that broke loose when the ship went down. He wiggled through, pushing his equipment ahead of him. Because of the narrow opening and possible entanglements, Ted chose not to run a line inside the ship. He decided that the spaces would be tight enough that there was no way he could get lost. He was confident in his ability to find his way out. He was wrong.

The divemaster on the surface watched the clock carefully. He was surprised when Ted didn’t surface the exact minute he predicted he would. The divemaster continued checking buddy pairs back onto the boat and getting everyone settled for the hour-and-a-half boat ride back to the dock. When he realized Ted was 10 minutes late, he began to get worried. At 15 minutes, with none of the other divers reporting seeing Ted in the water or on the anchor line, the divemaster entered the water. He made a quick search descending along the anchor line all the way to the bottom. He looked around the exterior of the ship for about five minutes and then returned to the surface. Ted was nowhere to be found.

ANALYSIS

The other divers on the dive boat had each made three decompression dives that day. None of them could return to the water to search for Ted. Even if the divemaster hadn’t made a dive that day, he was alone and wouldn’t have been able to search the ship for the missing diver.

The boat captain radioed in an emergency, but the crew and rescue officials quickly realized they were in recovery mode. Ted still hadn’t resurfaced 30 minutes past his planned time. He had clearly run out of breathing gas. A rescue was out of the question.

Ted was diving alone. Even though he had a comprehensive dive plan, there was no one to lend assistance when he got in trouble. He had entered the shipwreck without securing a line to the outside. When he got inside the engine room and got turned around, he couldn’t find his way back out. It is likely that he stirred up silt accumulated inside the ship. While the visibility was relatively good on the dive, at 200 feet the available ambient light was minimal. As the day progressed toward evening, the sun’s beams hit the water at a more oblique angle, causing even less light to make it to the bottom. Even if he had turned his lights off and let his eyes adjust to the gloom, it is unlikely he would have been able to see light coming from the entrance. Ted was essentially making a night dive inside an overhead environment and was completely dependent on his lights. Without a guide line to follow, there was no way for him to escape.

Ted was taking a couple of different prescription medications, including Ritalin, codeine, antihistamines and benzodiazepines. Very little is known about the effect of pressure on medicine, so it is possible those drugs played a role. Another concern is the conditions that required Ted to use the medications in the first place. Without a complete medical history, we can only guess, but it is possible he had anxiety and attention deficit problems. If entrapment lead to panic, made worse by anxiety issues, he might have failed to think through the situation and work on his own escape.

Ted most likely suffocated when he ran out of gas. We can hope he lost consciousness before then. If not, he spent his last few minutes on earth watching his pressure gauge slide toward zero.

A general surgeon performed the autopsy on Ted and declared the cause of death an air embolism. Since Ted never ascended, that is unlikely. More likely, the long deep dives and accumulated nitrogen in his system led to postmortem bubbling in both arteries and veins. The bubbles likely accumulated in the heart, leading to that diagnosis.

Lessons for Life:

1. Solo diving is not for everyone. If you want to dive solo, seek additional training and be prepared to carry the necessary additional equipment.

2. Any time you enter an overhead environment, when you can’t make a direct ascent, attach a line to the outside so you can find your way back out.

3. Consult a dive physician about any medical issues you might have and the effects of the medications you take for them.

4. Be honest on your diving medical form. Discuss any conditions with a physician familiar with diving medicine.

5. For the dive charter: Develop a system to perform a search-and-rescue operation at any dive site before leading divers there. There should be at least two divers qualified to dive at those depths who haven't been diving that day.

Eric Douglas co-authored the book Scuba Diving Safety, and has written a series of dive-adventure novels and short stories. Check out his website at booksbyeric.com.