Finding Purpose as a Search and Recovery Diver

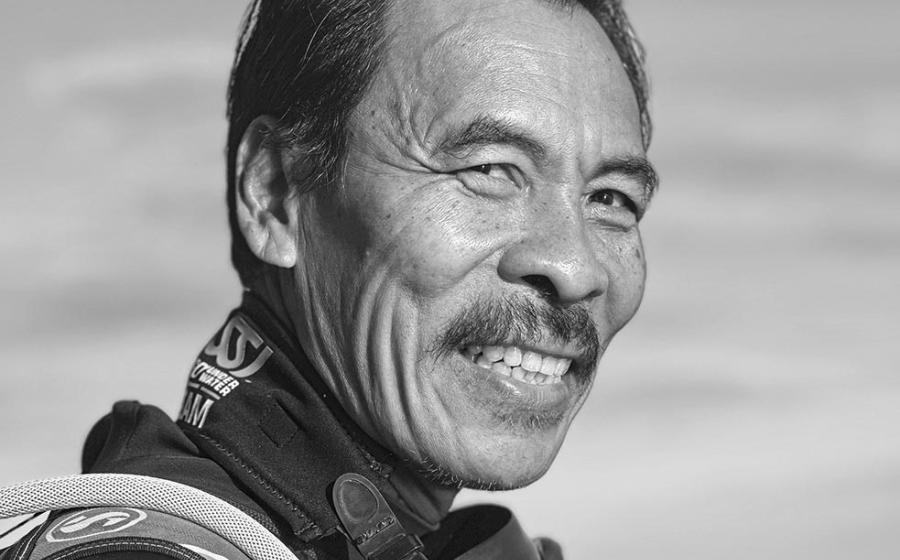

Christopher PerezA Legion diver dredges debris from a crash site at 130 feet to recover remains.

Nick Zaborski worked hard on every mission in his 23 years as a U.S. Navy diver. The service expects excellence and demands a high skill level. If divers pass training, they’re rewarded with camaraderie, purpose and the promise to descend to places truly extraordinary.

Pushing his body to extremes, Zaborski had gone down to repair ships, clear channels for safe passage and support efforts critical to national security. Quiet by nature, his mind roared with thoughts each time he embarked on a mission. He’d often take his last seconds before a descent to stare off into the distance, visualizing the dive before it even happened.

Related Reading: How Liveaboards Can Make You a Better Diver

Zaborski’s universe had always revolved around water. Raised in Wisconsin, he’d spent summers fishing and swimming at his family’s cabin on the lake. When a vacation at age 6 took him cross-country to San Diego, Zaborski stepped on the beach and saw the ocean for the first time.

Christopher PerezZaborski’s dive plan includes dredging for 70 minutes and 1.5 hours of decompression.

“From that moment on, the ocean was my entire life,” recalls Zaborski. “It was really that profound.”

After giving his youth to the Navy, a 41-year-old Zaborski looked forward to peace in retirement. He bought a boat, a truck and a dog, and figured he’d enjoy a quiet life in the mountains with his wife and two children. But after a year, he was miserable and couldn’t figure out why.

“I missed having a sense of purpose. I’d always had it in the military, even if I didn’t realize it. The thing that got me up in the morning was keeping my divers safe.”

Zaborski called his friend John Marsack, also a retired Navy diver, and discovered that he, too, needed a new mission. In 2018, the pair launched Legion Undersea Services and entered the commercial dive world.

Whether it was focus or fate, Legion caught the attention of the right people. Project Recover, a nonprofit that locates and repatriates the remains of missing service members, was expanding operations and needed a surface-supplied dive team. They wanted to speak to Legion.

Christopher PerezHe is using surface-supplied air and a communication unit.

Zaborski’s work had actually overlapped with Project Recover back in 2008. Having searched for a decade for a B-24J Liberator bomber that went missing during World War II, Project Recover, then known as the BentProp Project, had found the plane in the waters of Palau. They informed the U.S. government, which sent Zaborski and his team of salvage experts to recover the aircrew.

In 2021, Project Recover and Legion partnered for their first mission, a TBM Avenger torpedo bomber that had crashed in Palau in 1944—its three-man aircrew was never found.

With the operation only months away, Zaborski and Marsack got to work.

First, the pair arranged for all dive equipment, including a 6,000-pound recompression chamber, to be shipped 8,000 miles across the world from Florida to Palau. Needing a crew, they called on their Rolodex of retired Navy divers and filled 10 positions with veterans both eager and well-prepared to support the mission.

Drawing on decades of experience, Legion also drafted safe dive protocols for dredging debris at 130 feet while breathing surface-supplied air. Material recovered from the seafloor would be brought topside in a collection basket, while larger objects would be secured with cables and hoisted from the depths by crane.

Christopher PerezA diver ventilates his helmet during an in-water deco stop.

Once on the barge, debris and sediments would pass through Project Recover’s screening stations. Any human remains would be sent to a lab for DNA analysis, and if there was a match, the family would be notified and reunited with their loved one.

When the first day of dive operations for the mission began in August 2021, a rusty barge sat anchored in the blue waters of Malakal Harbor, Palau. On it, team members were a hive of activity as air compressors and generators hummed the soundtrack for their mission.

Before underwater recovery could begin, a pair of scuba divers would descend and mark the site with a buoy. It was only fitting that the Legion founders be the ones to do it.

.

Christopher PerezA Project Recover barge anchors above a wreck in Palau.

Zaborski stepped to the edge of the barge and looked to the horizon. His eyes shifted from the golden hue of the morning sky downward to the blue water. Resting 130 feet below was the wreckage of the TBM Avenger.

Zaborski and Marsack dropped into the warm water and began their descent. As they sank, the seafloor came into view and through dark water, they could see it—a twisted heap of metal tinted blue by transcending light.

Overcome with emotion, Zaborski raised his palm to high-five Marsack. Instinctively, the longtime friends came together for a hug at 130 feet below the surface.

The mission focus that had transfixed Zaborski was replaced with reverence and awe. In the silence between the sound of his own breaths, he could feel the presence of the men who rested here, connected by the pressure of the sea and the honor of service.

“It was one of those really profound moments in life,” recalls Zaborski. “It was a truly sacred place where brave men lost their lives.”

Zaborski took the buoy line from his hand and tied it to the wreckage. Then he reached into the Velcro pocket of his cargo pants and pulled out a mesh bag of coins. He found a secure spot upon the aircraft, which he later discovered was the fuselage, and rested the bag on top of it.

Christopher PerezA diver swims to a surface crane hook for inspection.

The challenge coin is a longstanding military tradition, one that represents the mission and the character of the person who carries it. They are presented as a recognition of service and achievement. The coins carried by Zaborski were commissioned by Project Recover to be presented to each team member when the mission was over.

With the buoy line tied, Zaborski and Marsack took a moment to explore what remained of the aircraft. The wreckage covered some distance, but Zaborski had memorized an image of the debris field and knew exactly where to go. After a moment of swimming, they spotted a single propeller blade sticking out of the silt with the engine still attached.

Related Reading: Finding Hope for Florida’s Bleached Corals

When they approached it, Zaborski reached out his gloved hand and grabbed the blade tightly. After so much work to prepare for this moment, touching the propeller assured him it was real. Overcome with emotion, Zaborski raised his palm to high-five Marsack. Instinctively, the longtime friends came together for a hug at 130 feet below the surface.

“We’d planned and prepared to such an incredible extent, and all of a sudden, I just came face-to-face with the thing that brought me here,” recalls Zaborski. “It was an unforgettable experience.”

Christopher PerezJohn Marsack performs hyperbaric chamber maintenance checks

“We’d planned and prepared to such an incredible extent, and all of a sudden, I just came face-to-face with the thing that brought me here.”

For the next 21 days, Legion collected what they could from the crash site in Malakal Harbor. When the fuselage, the majority of which had been buried under decades of sediment, was eventually hoisted to the surface, an opened parachute hung from its side. In the silt directly below where the challenge coins had rested, the team went on to recover human remains.

Zaborski admits that he could make more money chasing lucrative commercial contracts but insists he won’t be monetarily motivated.

Instead, he welcomes the fulfillment that comes with repatriating lost service members.

“Project Recover has created a vehicle for me to continue to serve, to have a purpose, and to focus the talents and skills I attained as a U.S. Navy diver,” says Zaborski. “I just can’t imagine a finer use for those skills.”