How Underwater Mapping Is Changing the Dive World

Candice LandauIan captures the edge of a reef that lies to port of the Kittiwake.

"This is not to scale,” our dive guide Tyler says as he rolls a beach towel on his leg and adds it to the pile of artfully shaped towels at his feet, one twisted into a sharp point to give it the appearance of a ship’s bow.

Though a whiteboard sketch of the USS Kittiwake sits behind him, Tyler is trying to bring the dive site to life to make it easier for us to orient ourselves once we’re underwater. He uses a paper cup for the funnel and three other towels for the various parts of the wreck’s superstructure.

I can tell we’re in for an excellent dive. The ocean is calm, a deep gunmetal blue that belies the clarity of the water in Grand Cayman, and there’s only one other dive boat at the site. If we time it right, we’ll have all 251 feet of the decommissioned submarine rescue vessel to ourselves.

Ian, Tyler, the author and Alex pose alongside one of Sunset House’s dive boats

Candice LandauIan captures video of the USS Kittiwake using two GoPros.

Reef Smart Guides founder Ian Popple and I are here to map the wreck. Or rather, I’m here to learn how Ian and his team create 3D maps of coral reefs and underwater features like the Kittiwake.

While Tyler’s towel model is fun and engaging, it’s briefings like these and the more typical whiteboard briefing that got Ian and his co-founders thinking about a better way to prepare divers for what they are going to see underwater. This need for improved orientation becomes even more apparent when considering dive sites with challenging conditions.

On the Kittiwake, visibility is usually good and current minimal, making for a straightforward dive. However, at more complex sites, a thorough orientation can be the difference between a successful dive and one fraught with safety concerns. Take, for example, the USS Spiegel Grove, a 510-foot-long wreck off the Florida Keys.

Its sheer size, coupled with the presence of multiple mooring buoys, demands a detailed briefing.

Divers must understand the layout and numbering of these buoys to avoid surfacing at the wrong location, a mistake that can be critical given the site’s often strong currents.

A photo-realistic map and a predive walk-through could prevent such errors.

Related Reading: Why Grand Cayman is the Perfect Family Diving Destination

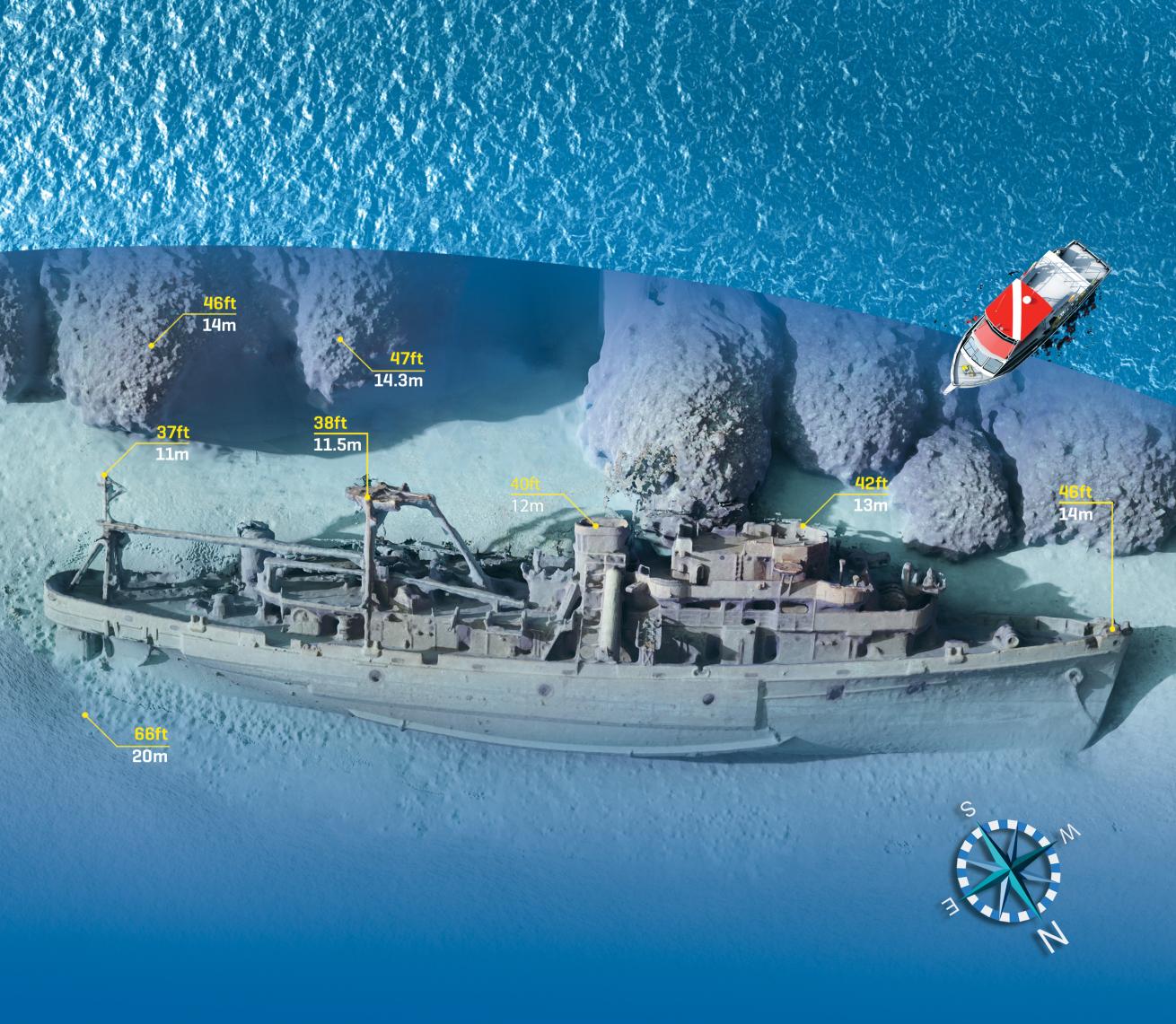

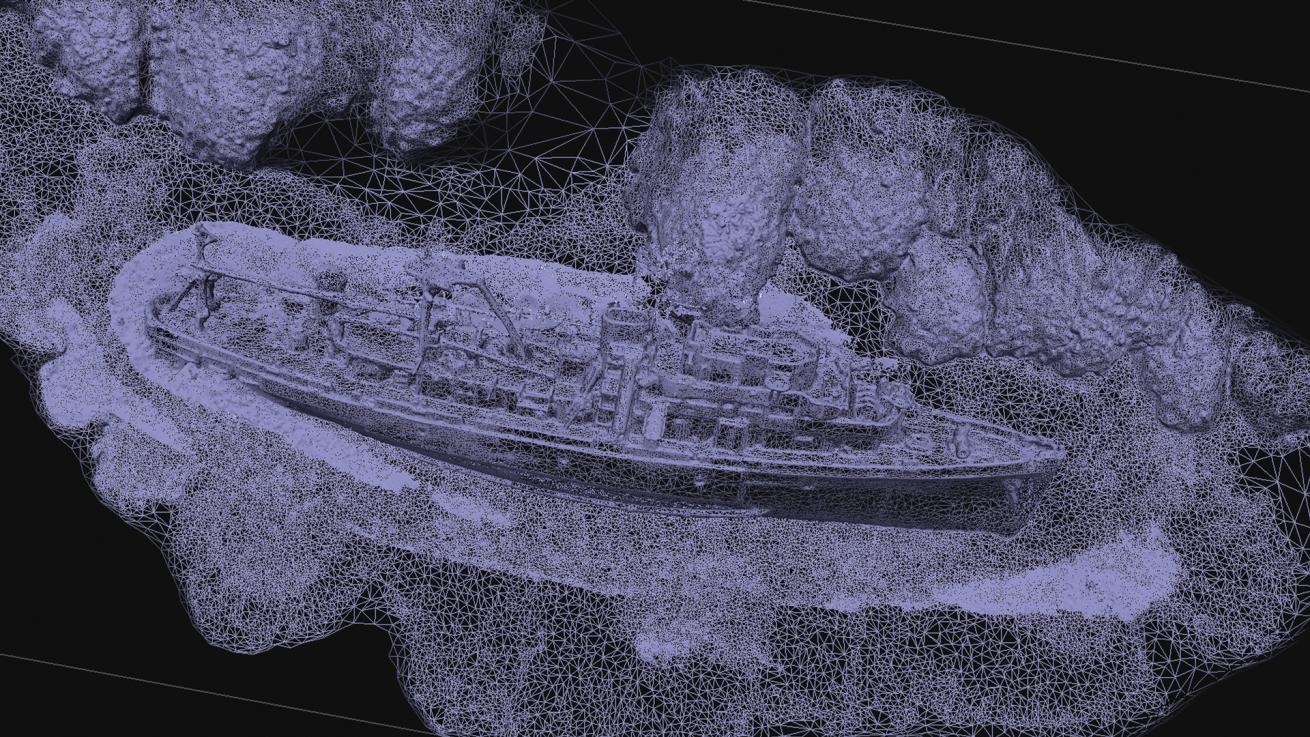

Reef Smart GuidesAn accurate model of the Kittiwake using photogrammetry data captured on our trip to Grand Cayman in early 2023.

FOR DAYS AFTER OUR CONVERSATION, I THOUGHT ABOUT THESE 3D MODELS AND ABOUT HOW THEY COULD CHANGE NOT ONLY THE DIVE BRIEFING EXPERIENCE BUT THE ACTUAL DIVE, ULTIMATELY MAKING IT SAFER AND MORE ENJOYABLE.

A Glimpse of the Future

I met Ian over Zoom in 2022. His passion for his work was immediately evident. As he walked me through the products Reef Smart Guides creates for dive shops, resorts and divers, he became even more animated. Our conversation soon turned to the aspect of his business he believed would revolutionize a diver’s underwater experience: the company’s 3D models. As someone fascinated by virtual and augmented reality, I was instantly captivated.

Candice LandauIan briefs our plan for the dive.

“Do you need a VR headset?” I asked, eyeing my Oculus Quest across the room.

“No,” he said. “All you need is your phone. In fact, why don’t you try it right now?” He sent me a link to the 3D models section of Reef Smart Guides’ website and had me click on one of the wrecks. I selected the MV Courageous, sunk off Destin, Florida. “In the bottom right corner, you’ll notice a little icon that says ‘AR.’ Click that and it should pull up a QR code. Scan the code and follow the instructions.”

Within moments, a virtual model of the cargo vessel materialized on my desk. “Pinch your screen to resize it, and then move your phone around to explore,” Ian said.

I was surprised when I realized not only could I tour the exterior of the ship, even going so far as to make out its name, but I could also navigate my way inside it. I felt the urge to duck beneath the twisted metal that seemed to loom everywhere. A compass rose lay on the virtual seabed nearby, providing clear headings for a real dive. I could easily envisage a divemaster on a liveaboard, gathering divers around a table for a lifelike predive briefing.

Related Reading: The Cayman Connection: Why Liveaboards Are Great for New Divers

For days after our conversation, I thought about these 3D models and about how they could change not only the dive briefing experience but the actual dive, ultimately making it safer and more enjoyable.

The question for me wasn’t if this would become a reality, it was when.

Candice LandauIan with the relatively simple equipment of his trade—two GoPros

Surveying the Deep

The moment Ian and I enter the water, I realize I’ve made a huge mistake. My silt-safe finning style is not complementary to the speed at which Ian moves, and I internally chastise myself for not anticipating this.

At 251 feet, the Kittiwake’s length may not sound extensive, but Ian’s need to capture it from multiple angles and make several passes to gather enough data points means a lot has to be accomplished within the confines of a single dive, especially one with limited time.

I’m relieved that he has opted to leave his small scooter behind, choosing instead the deceptively simple tools of his trade: a horizontal tray with two GoPros on either side and a single high-powered video light in the center.

Candice LandauA diver poses on the helm of the USS Kittiwake.

While my task is to photograph Ian’s work, there isn’t much to observe directly. The real magic happens post-dive when the videos are transformed into a series of data points that the modeling software then triangulates and interprets.

However, there’s a wrong way and a right way to capture the footage, something Ian and his team have fine-tuned through trial and error. Timing our dive to avoid other divers is crucial, as their presence can obstruct parts of the scene, leading to gaps in data capture and inaccuracies in the final 3D model. But it’s not just divers—schools of fish, bubbles and even the constant movement of the underwater environment can pose challenges.

The software is designed to pick up consistent elements across a series of photographs, but anything transient, such as a passing fish or diver, is filtered out. Shadows also present hurdles; they can create dark areas in the footage, obscuring details and complicating post-processing. Light levels can change dramatically underwater, with a passing cloud or the sun’s angle altering the visibility of the dive site. All these factors combined can significantly affect the post-processing and alignment of images, and thus the overall quality and accuracy of the photogrammetry model.

We use the full hour allotted to us, and I observe and snap photos, all the while pondering how simple GoPro footage can become a complex 3D model.

Candice LandauA diver checks out the wreck of the Kittiwake.

Back on the boat, we switch tanks and ensure our various cameras and lights are charged.

“Do we need another dive on the wreck, or have you got enough data?”

Ian is confident he’s got plenty of usable footage and suggests we check out the Doc Poulson, a Japanese tug that he and the team have mapped before, albeit without the use of photogrammetry.

As we skim across the water to the new site, Ian addresses my earlier question. “For a large wreck or a reef, we might need multiple dives. But for most sites, a single dive provides enough data to create a 3D model.”

He then shares an exception: the RMS Rhone, mapped earlier in 2023. This historic wreck, which sank in the 1800s during a hurricane off Salt Island in the British Virgin Islands, is spread out over a large area with distinct sections: the bow, stern and several midsections.

“Each part of the Rhone is almost like its own wreck,” Ian explains. “You might start mapping the bow and realize it has areas within it that also need mapping. After one dive, you’ve only covered the bow.”

Related Reading: Embracing the Deep in Chuuk Lagoon

To fully capture the Rhone, Ian’s team had to undertake several dives. Our dives are simple in comparison. The Doc Poulson is much smaller than even the Kittiwake, and once Ian has taken all the passes he needs, we explore the nearby reefs, watching the many sand eels wafting like grass in a gentle breeze, bodies stretching out of their sand burrows.

Putting It All Together

Candice LandauThe author conducts an interview with Ian to learn about the mapping process.

Later that day, Ian and I head to our hotel bar at Sunset House. It’s a popular spot on Grand Cayman, overlooking the water and the unique rocky limestone shore, a terrain known as ironshore. We order mudslides and talk about what happens now that we’ve wrapped up the filming.

“Next, we send it all to Peter.” Ian says. While I’m disappointed Peter McDougall, Reef Smart’s technical wizard and co-founder, isn’t with us on this trip, I’m keen to understand the steps he will undertake to transform our footage into a detailed 3D model.

Ian explains how Peter will use Agisoft and Blender to transform the videos. First, he’ll have the software isolate frames from the video footage we captured, effectively turning it into individual photos.

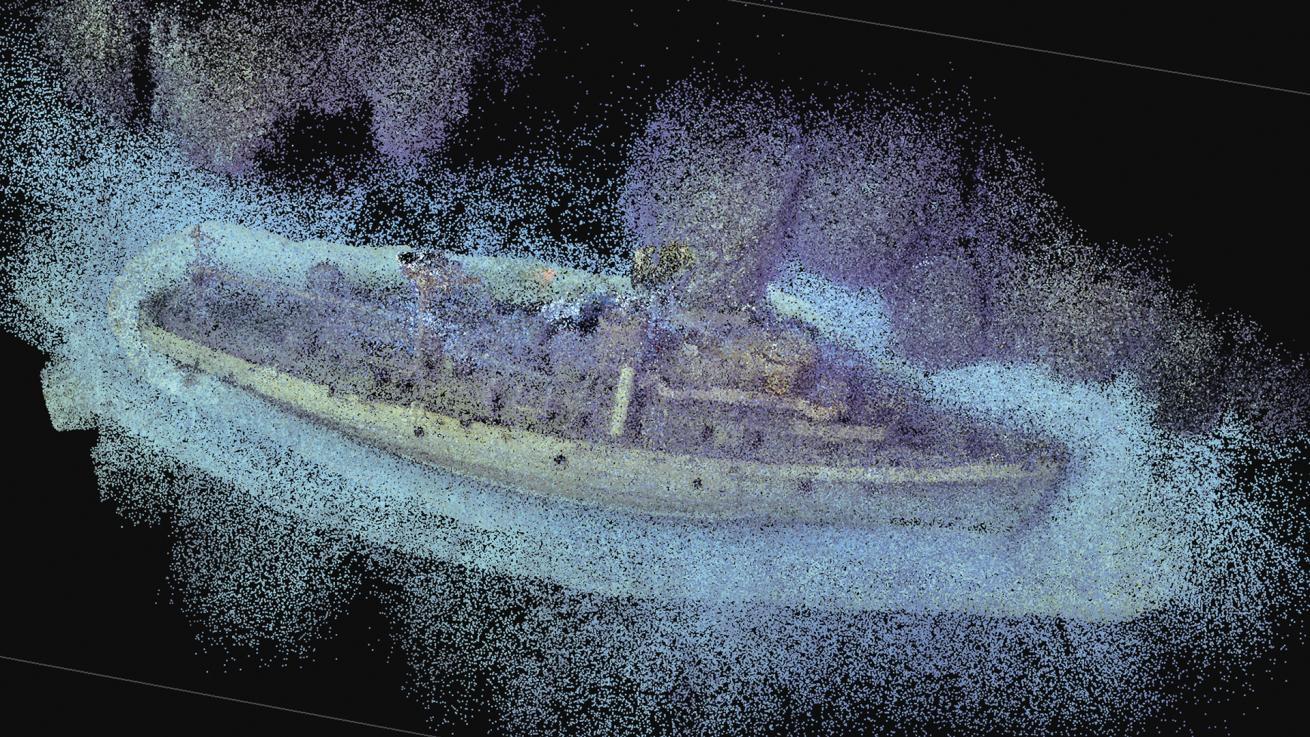

These photos, taken from various angles, are then analyzed for overlapping points to create a point cloud model. This model is a digital representation of the underwater site, where each dot in the point cloud represents a point in space matched by the system between two or more aligned images.

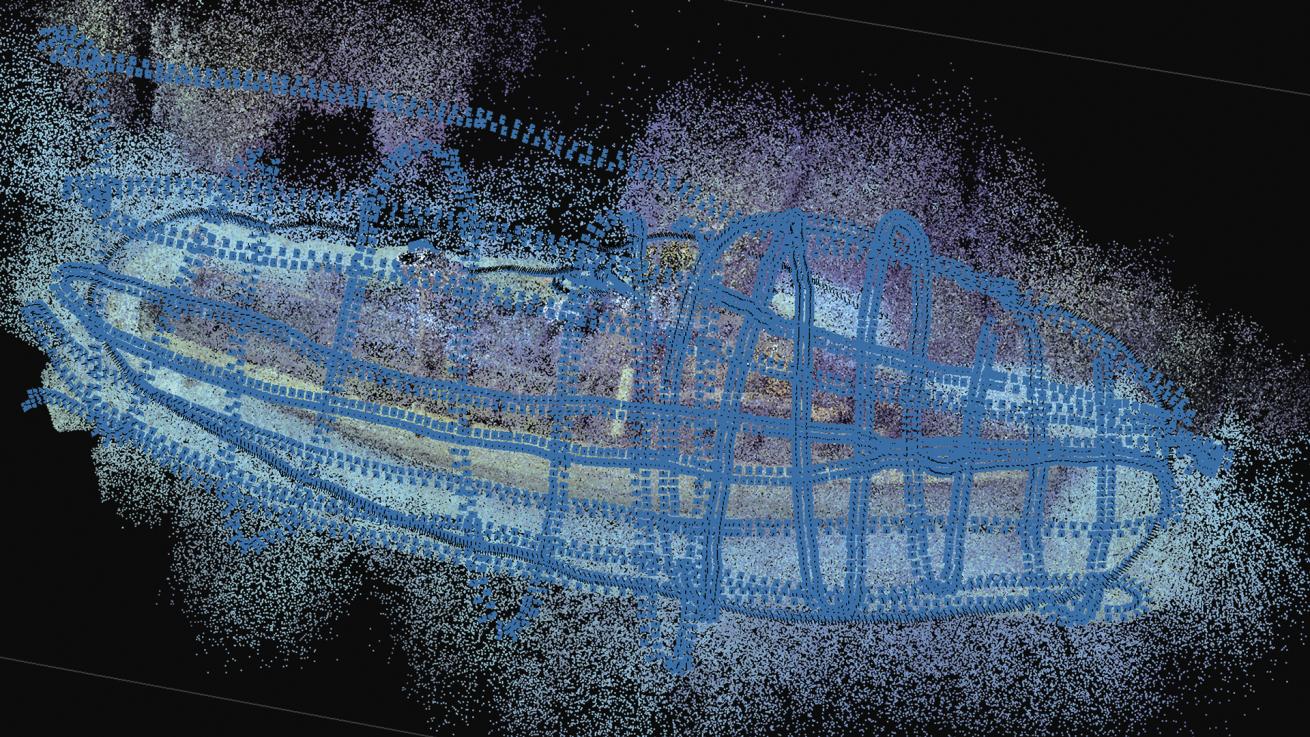

Once the point cloud is complete, Peter assesses it with overlaid camera shots. These indicate the estimated position and orientation of the images captured as we mapped the site, illustrating the necessary overlap to capture the full site.

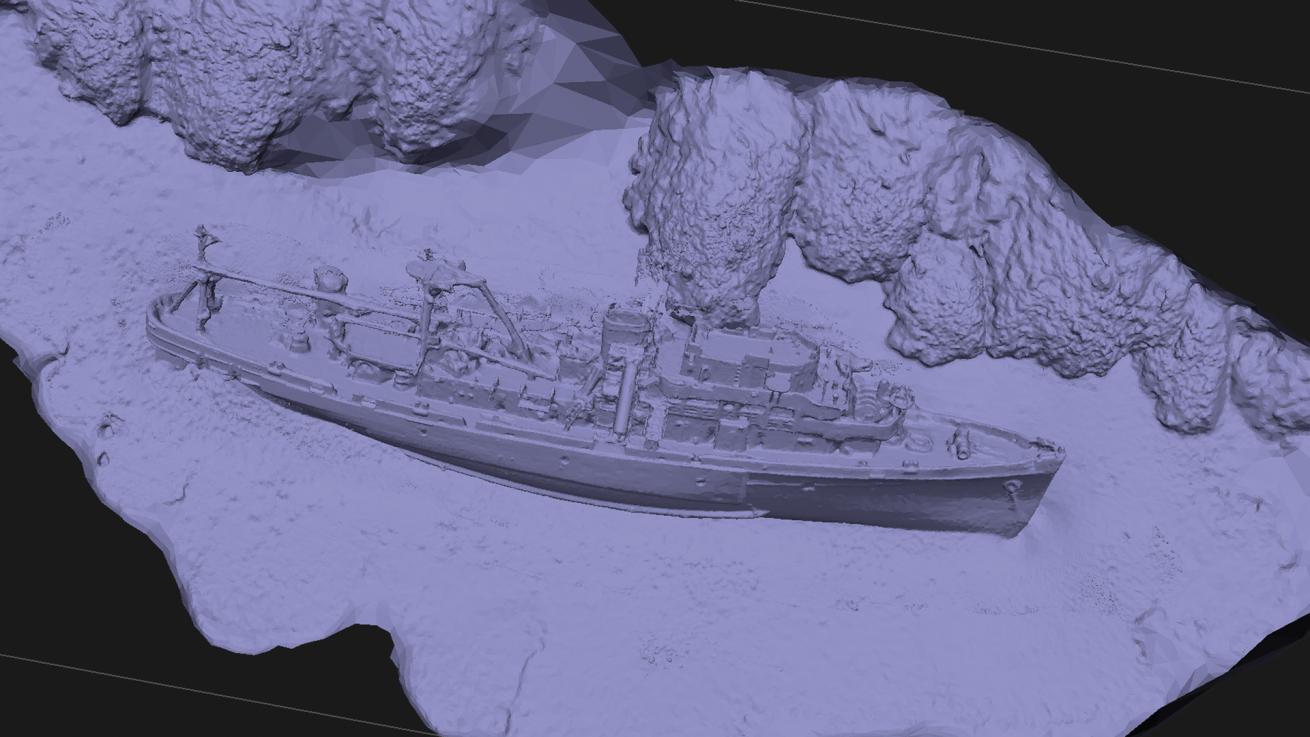

With the point cloud in place, the software generates a mesh. A wireframe view of the mesh shows how the vertices are connected, forming small triangles in the process.

INTRODUCING PEOPLE TO THE UNDERWATER WORLD WE LOVE REALLY COULD BE AS SIMPLE AND FUN AS THIS IS.

Next, Peter adds texture to the mesh based on thousands of image stills extracted during the process. This texture is a faithful representation of the site’s appearance at the time of mapping. The textured 3D model is then exported for use in modeling software.

Steps of Mapping a Wreck

1 POINT CLOUD SHOTS: This is the first step, where each dot in the point cloud represents a point in space matched by the system between two or more aligned images. The point cloud is generated from thousands of separate images.

2 POINT CLOUD WITH CAMERA SHOTS: The blue rectangles overlaying the point cloud represent the estimated position and orientation of the images captured by the diver as they mapped the site. These help illustrate the amount of overlap necessary to properly capture the full site.

3 MESH SHOTS: With a complete point cloud in place, the system can turn to generating a complete mesh, which represents a set of vertices each connected to one another to form triangles called faces. The more complex a site, the greater the resolution required to properly capture all of the necessary details.

4 WIREFRAME SHOTS: A close-up of the mesh shows how the vertices are connected in various directions to one another, forming small triangles in the process. The larger the triangles, the less detail in that portion of the model.

5 TEXTURED SHOTS: The system generates a color texture for the mesh based on the thousands of images taken during mapping. In this way, the texture is a faithful representation of how the artificial reef looked at the time the mapping took place.

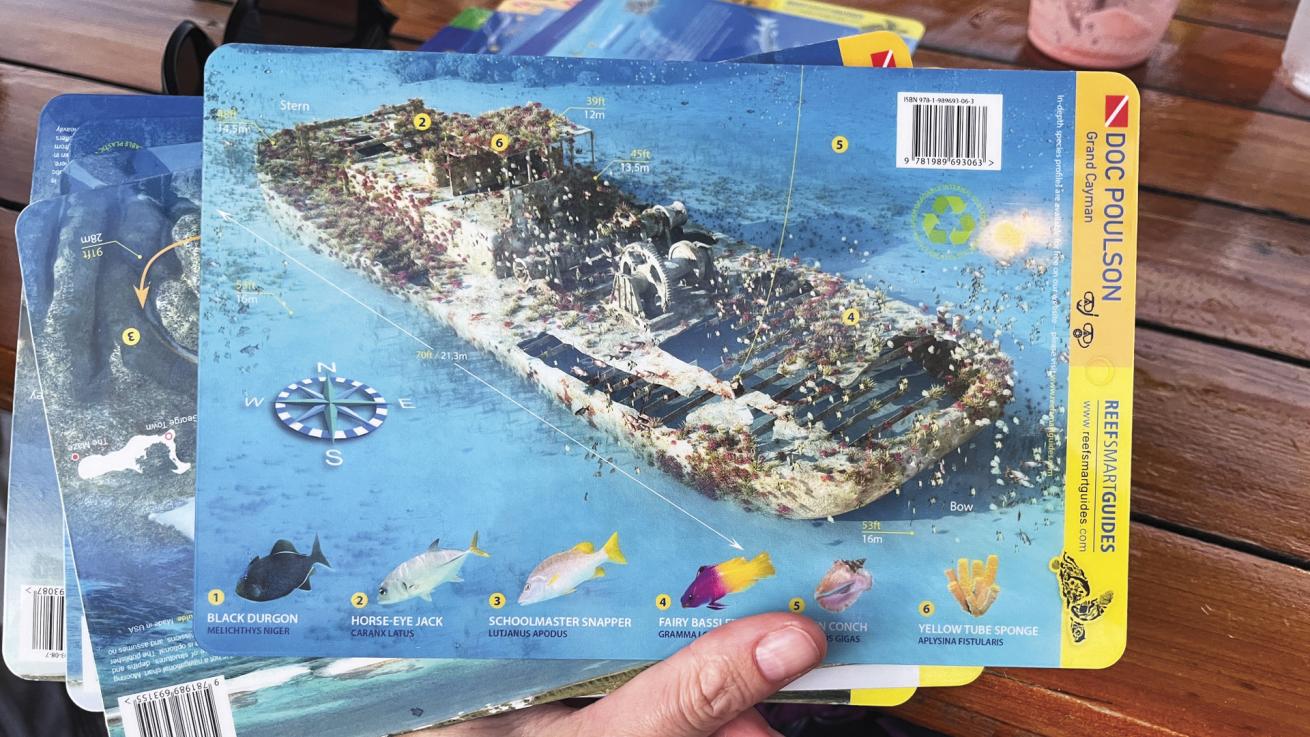

Reef Smart GuidesReef Smart Guides’ waterproof laminated briefing cards.

The final step involves Reef Smart Guides’ co-founder and graphic design guru Otto Wagner, who adds many of the bells and whistles divers need to better understand the environment they love to explore, like compass, depths, routes and species. Otto makes entire underwater scenes pop in the 2D designs that Reef Smart Guides creates, such as waterproof handheld cards, briefing charts, shoreline signage and their expanding series of guidebooks. The result is a 3D model, an invaluable tool allowing divers to virtually explore a site before the dive even begins.

View the 3D models—featuring augmented reality—of the USS Kittiwake as well as several other sites Reef Smart Guides mapped in Grand Cayman: Amphitrite and the LCM David Nicholson and Doc Poulson wrecks.

At some point, our waitress stops by to refill drinks and curiously asks what brings us to the island. Ian, ever the enthusiastic ambassador for his work, explains that we are here to map some of the local underwater features. Eager to share a tangible piece of our project, he stands up and pulls out his phone. With a few taps, he brings up an augmented-reality model of a wreck. The waitress watches in astonishment as Ian places the virtual wreck on the floor, allowing her to walk around and explore as if she were diving the site herself.

I can’t help but smile. Introducing people to the underwater world we love really could be as simple and fun as this is.

Related Reading: Delve Into Tec Diving on a Red Sea Vacation

Candice LandauOur waitress at Sunset House goes on her first AR dive.

The following morning, we set out to dive our hotel’s house reef, an easy shore dive that grants us access to two notable features we want to map: the iconic mermaid of Sunset House, known as Amphitrite, and the LCM David Nicholson, a U.S. Navy landing craft wreck.

I’m pleasantly surprised to find one of Reef Smart Guides’ maps is a permanent fixture at the entrance to the site. A group of divers is gathered around it, planning their dive. I wonder what they’d think if they could scan QR codes on the map to view augmentedreality representations of each feature.

Ian circles Amphitrite, colloquially known as the mermaid or the Siren of Sunset House. Designed and crafted by Simon Morris, Amphitrite is 9 feet tall and rests in about 50 feet of water, poised looking out to open ocean at the Sunset House reef.

An hour later we’re back on shore, washing gear and wrapping up. In just two short days I’ve been sold on the value of photogrammetry and the potential for it to change our underwater experience. Not only will 3D and AR maps make dives easier to plan and safer as a result, but they’ll also be useful tools for monitoring change over time—in reefs for example—and for mapping historical underwater features. It feels as though we’re on the cusp of a new era in diving, one in which the mysteries of the deep become more accessible than ever before.

What is Reef Smart?

Reef Smart Guides was formed in Montreal in 2016 by several avid divers profoundly missing tropical diving. Ian Popple and Peter McDougall met as marine biology graduate students, and creative director Otto Wagner was a design graduate from a nearby university. Together they developed a system for 3D mapping reefs and wrecks, which they field tested in Bonaire. Today, ReefSmart Guides’ 3D models of wrecks and reefs help divers and snorkelers explore underwater sites, as well as raise awareness, improve safety and help dive operators and resorts attract more divers.