Why Scuba Diving Regulators Freeze

How can a reg freeze in 50°F water?

“I think a lot of divers don’t realize it, but the physics of it all are really complicated,” says Mike Ward, president of Dive Lab in Panama City Beach, Florida, where ScubaLab conducts objective testing of regs each year.

Ward should know. A retired U.S. Navy diver, for almost 20 years he’s been studying why regs freeze, icing them into failure in Dive Lab’s ANSTI breathing simulator.

Scuba Diving magazineHow to avoid a frozen regulator

The many variables that determine whether a reg fails in cold water include tank pressure, breathing/flow rate, dive time, reg design and water temperature, Ward says.

Tank pressure and flow rate are key because they work together to make the reg cold. As air flows from the tank through the reg’s first stage and pressure drops, the gas rapidly expands and cools. The bigger the pressure drop and greater the flow, the colder it gets.

“It’s basically how air conditioning or refrigeration works,” Ward says.

The longer the dive time, the colder the reg can get.

Reg design is important because first stages with more mass and surface area (like ribs) can better draw heat from the water. Second stages that isolate the frigid inlet-valve area from moist exhaled air, and that have exhaust designs that minimize water entry, can better stave off freezing, Ward says.

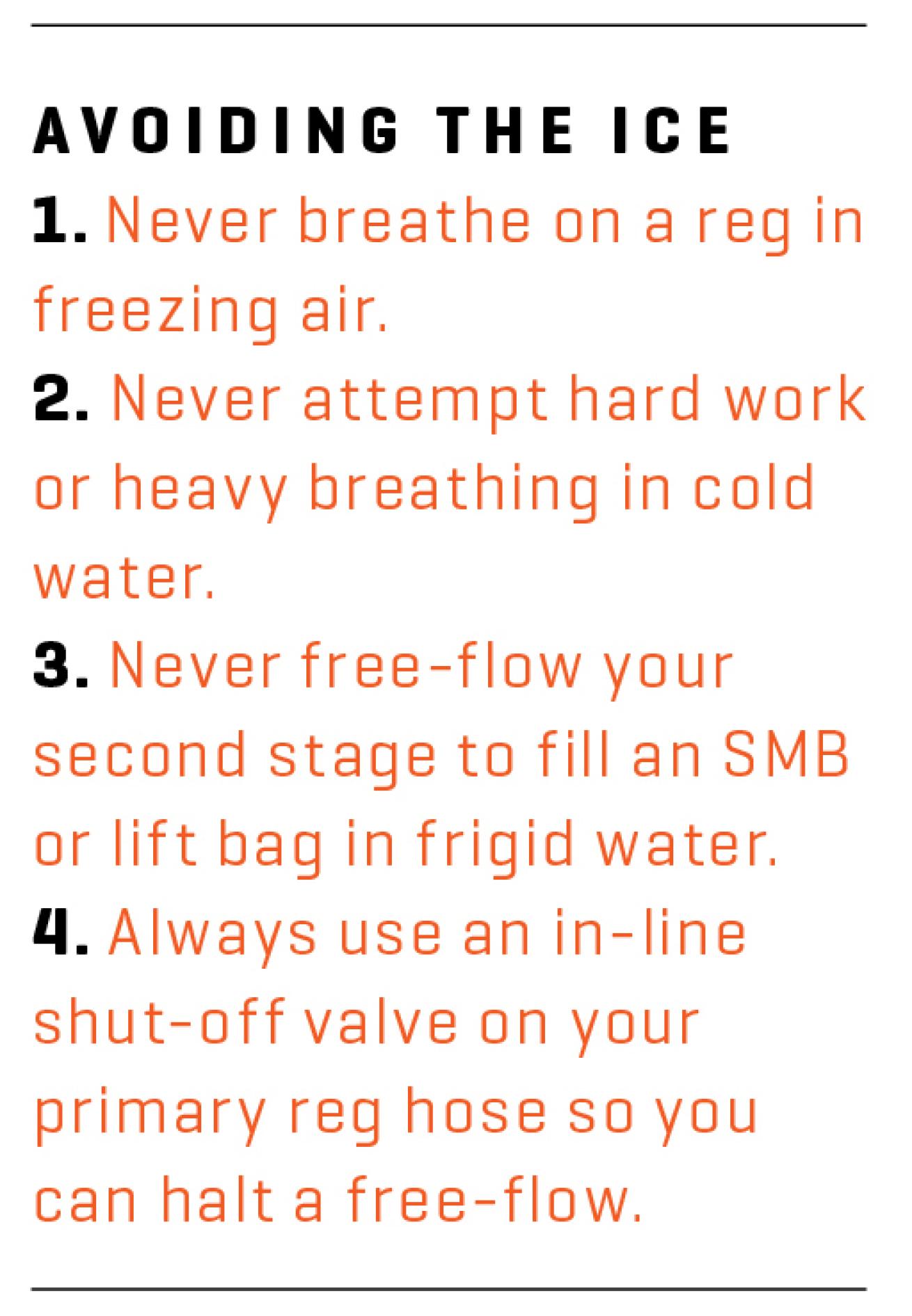

Water temperature’s role is somewhat counterintuitive because it’s the water’s warming ability that keeps the reg from freezing. (That’s why training emphasizes not breathing on a reg above the surface in subzero air, where it can quickly ice up.)

“The water is actually your friend,” Ward says. But once water gets below about 40°F, it doesn’t have enough heat to warm the reg as fast as it can be chilled. There are a variety of ways a reg can fail. Ice on the second-stage inlet valve can block the valve from closing after an inhalation. Thick ice around the first stage can block water flow to the diaphragm or sensing ports, causing a free-flow.

None of this requires water anywhere near freezing. We’ve watched Ward freeze regs into free-flow in as little as 10 minutes in water as warm as 50°F.

But the colder the water, the more quickly things can go wrong, as Ward demonstrated following this year’s reg testing at Dive Lab, when he ran a cold-water reg on the simulator in 38°F water with temperature sensors inserted into the low-pressure hose where the air exits the first stage, and where it enters the second stage. (Gas is coldest leaving the first stage and warms as it passes through the hose, which is itself warmed by the water.) After just a couple of minutes of heavy breathing (25 large breaths a minute) with tank pressure at 3,000 psi, the lowest temp reached about minus 3°F leaving the first stage and about 26°F entering the second stage. After five minutes, ice was forming on the first stage.

Mike Ward/Dive LabA frozen regulator at Dive Lab

By 10 minutes, as ice built around the second-stage hose fitting, we did some of the things cold-water training emphasizes not to do.

Pressing the BC inflator for five seconds sent the first-stage temp down almost instantly to about minus 9°F. A single five-second press of the purge was enough to send the first-stage temp below minus 16°F and the second stage below 0°F. It’s worth noting that in our demo, the reg was just below the water’s surface. But, as Ward’s research has shown, the chilling effect is even greater at depth because of the increased air density. While well-designed regs are more resistant to freezing, Ward says, divers should understand that in frigid water, powerful physical forces are working against them.

“In the right conditions, you can make any reg freeze,” he says. “That’s nothing against the reg; it’s just physics.”

To learn more, download Ward’s detailed report of his research, “Scuba Regulator Freezing: The Chilling Facts” here.