Scuba Diving Iceland Beyond Silfra

Franco BanfiA composite shot brings together the topside and underwater thrills of heli-diving in Iceland.

Perched on the edge of the Atlantic, Iceland is one of the most geologically active places on Earth. Home to hundreds of volcanoes, geysers, smokers, fissures and hydrothermal vents, it straddles the rift zone between the North American and European continental plates and lies just below the Arctic Circle, with the small off shore island of Grímsey the only part of the country that actually touches that latitude. Most visitors come to take in the stark volcanic landscapes, visit the thundering waterfalls, tour historic cities, and hope to see the mesmerizing northern lights vanishing in a kaleidoscope of green and red. Scuba divers journey here to submerge in some of the clearest fresh water on the planet.

Iceland is a country of contrasts. Above and below we feel the power of nature, amplified by the clarity of the air and water, which reflects the contrast of colors and scents. Blue is the natural color of the purest water and sky I’ve ever seen. Cold, wet and slow, it fills the freshwater fissures, distinctly different from the red warmth, fire and intensity of active lava flows from countless volcanoes (although many more are dormant). The black of basalt rocks and the darkness of the long winter nights are in total contrast to the pure white of the untouched snow covering the glaciers, the whipped-creamlike clouds running in a pure blue sky, and the almost 24 hours a day of shimmering light in June.

Franco BanfiA scuba diver inside the volcanic crack Nesgjá in Iceland.

Floating on Earth’s mantle, where continental plates meet and drift apart, Iceland is in never-ending motion, inspiring visitors to explore its most remote locations. At the same time, Icelanders respect and value time to relax, contemplate, and converse over a good meal. It’s a world worth exploring, from its famous and iconic places to the ones that are kept secret in the hearts of Icelanders.

Franco BanfiScuba divers at Davíðsgjá in Iceland.

CRYSTAL-BLUE PERSUASION

With luck, I bump into an Icelander who knows this country like the back of his hand, a world traveler who yearns to share the wonders of his island. From Davíð Sigurþórsson I happily discover that Iceland is more than famous Silfra and Strýtan — and I learn that those iconic places are more than just the classic images we have all admired.

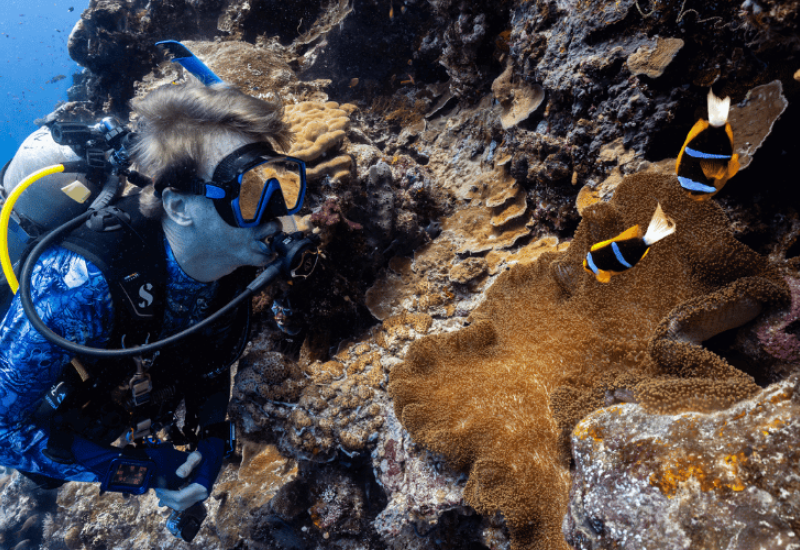

Crystal-clear blue is the dominant color of freshwater dives in Iceland. The best-known, Silfra and Davíðsgjá, are the two divable rifts in Thingvellir National Park, but there’s also the gem of Nesgjá, in the north of Iceland, and other unnamed spots. Silfra is a large freshwater spring — about 16 by 32 feet wide, 20 to 40 feet deep and more than 650 feet long — where water from the nearby glacier Langjökull surfaces and runs into the lake Thingvallavatn. It’s the most crowded spot in Iceland in the tourist season, and its main attraction is the clarity of the water, which gives divers and snorkelers the feeling of flying above the bottom. On sunny days, when there are ripples on the surface, the light breaks into a rainbow, creating a beautiful display.

Nesgjá is shallower, shorter and smaller than Silfra, but amazingly beautiful, with its cobalt-blue glacial meltwater and geological formations ending in chiseled basalt rocks.

While entry and exit at Silfra is easy due to the large platforms and ladders leading to the water, diving Nesgjá requires a more frontier-style approach. You need a vehicle able to climb a snow-covered hill and cross the short route heading to the fissure. Then you have to walk a few yards in the snow, carrying your scuba diving gear, and climb basalt rocks until you reach the water and proceed to literally jump in from the edge of the crack.

Franco BanfiNesgjá as seen from above.

Then there are the fissures that have no name, the real “secret spots” beloved of resident divers, where you have the opportunity to dive only if you have the right guide. Some of them require “superjeeps” or a helicopter to access and must be carefully organized in advance. Scuba equipment is wrapped with a sturdy net that is hooked to the helicopter and dangles free during the transfer to the site. Early in summer, when the snow level is reduced, superjeeps can climb these lunar mountains and hills, helping with the transport of equipment, but the journey by vehicle can be uncomfortable.

There are no refill stations, no shops, nowhere to take shelter from blowing winds, no bathroom, no services if equipment fails. There is only the wild, with no frills: desert rocks covered with lichens, uncountable hidden crater lakes and lava fissures filled with pure, sweet water. With no other divers around but my buddy and Sigurþórsson, we spent hours cherishing the beauty of the mirrored surface and the play of light on the stunning tectonic scenes. There is no significant current in the fissures; most of the cracks are shallow, easy dives. Yet gliding between the American and European shelves, exploring the basalt landscape, it’s important to respect the demands of low- temperature diving (35 to 40 degrees F) and buoyancy control in a drysuit. But for the properly prepared scuba diver, these spots create a sense of calmness and relaxation — the paler the blue, the more freedom I felt.

Franco BanfiA wolf eel at Little Strýtan in Iceland

EMERALD DREAMS

Next on the spectrum is green, the color of growth, renewal and rebirth. I plunge into the emerald northwestern sea, close to Miðfjörður e Húnafjörður, where there are huge colonies of seals so shy, it was hard to interact before the almost-Arctic waters demanded an exit. In terms of the food chain, these rich, green waters are an important area for Iceland’s fishing industry.

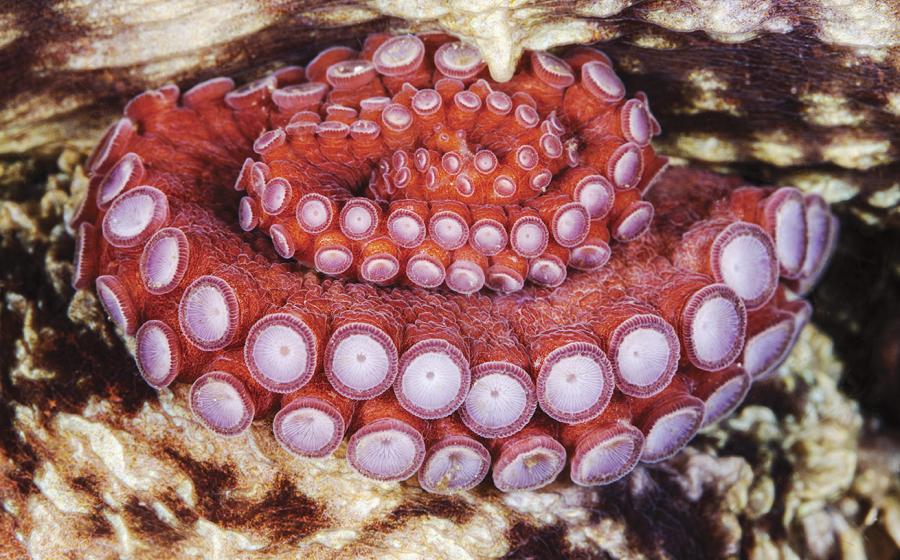

The northern waters are a paler green; in Eyjafjorður, close to Akureyri, dense phytoplankton and algae blooms support unbelievable ecosystems around the hydrothermal chimneys of Arnarnesstrytur, including wolffish, lump suckers, schools of inquisitive cod, crustaceans, and a plethora of invertebrates from giant sea cucumbers and anemones to nudibranchs. Here the highlight is Strýtan, a shallow, alkaline hydrothermal vent that has created a large cone reaching 180 feet from the seafloor. Scientists estimate more than 1,500 gallons per minute of 167-degree water pours from the cone. Strýtan started developing 10,000 years ago and is made from magnesium-silicate; it was one of the first protected underwater areas in Iceland.

Arnarnesstrytan — “little Strýtan” — is north of the village of Arnarnes, on the west side of the fjord. The system is comprised of hydrothermal chimneys in a 550-yard line. Many individual and overlapping chimneys rise to 30 feet above the seafloor. The cone-shaped stacks are covered with pink algae and mineral deposits.

Fluids from hydrothermal vents originate from seawater, which percolates into the oceanic crust and is heated at the top of magma chambers or in hot rock formations. The hot fluid, discharged from the seafloor, is anoxic and acidic. Elements dissolved in the hydrothermal fluid precipitate around the vents, commonly forming characteristic chimney-like structures. In such an extreme environment, diverse types of thermophilic microorganisms have been detected and isolated.

Franco BanfiGoðafoss, known as the “Waterfall of the Gods.”

WARM HEARTS, WARM LAND

Iceland appeals to scuba divers as warm and passionate as the generous people living here. In contrast to the cold temperatures, I found a warm welcome everywhere, and simple gestures of friendship that go straight to the heart. Stripped to its essence, this volcanic island exists on the beating heart of the living Earth, and this is reflected in the sincere and direct character of its open-hearted residents.

Iceland’s volcanic activity and bursting red lava continually generate new land and territory to be explored, much like the spirit and the nature of the Icelanders, continually meeting new friends who will be invited to come back again and again.

Franco BanfiSeals watching the scuba divers from afar in Iceland.

NEED TO KNOW

Dive Season Scuba diving in Iceland is done from late April to early October, to take advantage of the long daylight hours in summer.

Dive Conditions Freshwater temps are 35 to 40 degrees F, with visibility of more than 150 feet. Seawater temps are slightly warmer, from 40 to 43 degrees F. Visibility is much reduced, to around 40 feet in green seas.

Travel Tip SAS, Icelandair and low-cost airlines like Icelandic WOW air are all good options for getting to Keflavik International Airport in Reykjavik.

Dive Operators Our guide, Davíð Sigurþórsson, operates Iceland Dive Expeditions out of the capital city, Reykjavik (facebook.com/icelanddiveexpeditions.is; 011- 354-578-6200 or 011-354-770-3777).

Price Tag A day tour of the Silfra fissure, including transfers, guide, two dives, and all equipment and fees is about $400. A three-day dive tour, including five salt- and freshwater dives, a guide, tanks and transport from Reykjavik, is about $1,150. A five-day tour, including four nights’ accommodations, land and sea transfers, some meals, six guided dives and a snorkel, is about $3,150. Dives requiring a superjeep or helicopter are priced on request.

What It Takes Divers should be fit, in good health and comfortable diving in a drysuit with thick insulating undergarments, with at least a moderate amount of logged dive experience and drysuit certification.

Franco BanfiA lumpsucker at Little Strýtan.

Franco BanfiTips for photographing Iceland.

5 TIPS FOR SHOOTING IN ICELAND

1 Shoot using natural light as much as possible, even if this is a challenge.

2 Push the ISO of your camera as high as is tolerable without causing too much “noise.”

3 Lack of contrast can make it difficult to depend on autofocus in cold water. Sometimes it simply won’t work, so it’s important to always have access to manual focus.

4 Open your housing only in a low- humidity environment prior to diving to prevent fogging issues when submerging in cold water.

5 Find gloves that fit you and allow you to access small dials and buttons on your housing.

Underwater Photo Gear Franco Banfi uses a Canon EOS 5D Mark III and EOS 5DS, Canon EF 15mm f/2.8 fisheye, Canon EF 8-15mm f/4L fisheye and a sturdy aluminum housing with dome ports specially fitted for low temperatures.