Construction Unearths 15-Million-Year-Old Snaggletooth Shark Skeleton

15-million-year-old tooth and vertebrae from Snaggletooth Shark find

left: A fossil snaggletooth shark tooth (Hemipristis serra) from the Gibson’s find. It is still partially covered in the reddish-colored ocean-bottom sand that buried the dead shark during the Miocene. right: One of the fossilized spool-shaped snaggletooth shark vertebrae from the Gibsons' backyard. The shark skeleton was so close to the surface that grass roots are visible in one of the openings in the top of the vertebra that held the base of the neural arch.

S. Godfrey

This Halloween, the Gibson family in Chesapeake Bay, Maryland, had a surprising visit from the dead. While digging a foundation for the construction of his parent’s sunroom, Donald Gibson unearthed the 15-million-year-old grave of a snaggletooth shark. It’s also the most complete fossilized skeleton of the species ever found, including roughly 80 vertebrae and hundreds of teeth.

After the Gibson family called on archaeologists from the Calvert Marine Museum for excavation aid, the unexpected relic was identified as the extinct ancestor to Hemipristis elongata, now native to the Indo-West Pacific ocean region. Also known as the fossil shark, Hemipristis elongata is the only surviving member of the Hemipristis genus and listed as “vulnerable” on the IUCN Red List.

"I really hope that this fossil snaggletooth find will draw attention to the plight of the living snaggletooth shark," Godfrey said. "[Throughout] much of its range, its numbers have been severely diminished by over-fishing."

So how did this 15-million-year-old shark end up so well-preserved in the Gibsons’ backyard? Back when this particular shark was swimming, the Atlantic covered most of the coastal plane. As the Earth changed, sediment from the mountains flowed down rivers that fed into the Atlantic. According to Dr. Stephen Godfrey, Curator of Paleontology at CMM, the shark likely got caught in a storm-driven, underwater sand wave, which protected the shark’s delicate cartilage along with its unique teeth. One tooth is covered in smaller teeth that border both edges.

In December, CT scans will be taken of the skeleton, and for the first time archaeologists will be able to see the true dentition of this shark’s mouth.

"We can associate the size and shape of these snaggletooth teeth with the size and shape of its vertebrae, something that until now has not been possible," Godfrey said.

So, locals got more than just candy for Halloween. Those going by the Gibson residence could see archaeologists carefully extracting seriously rare history.

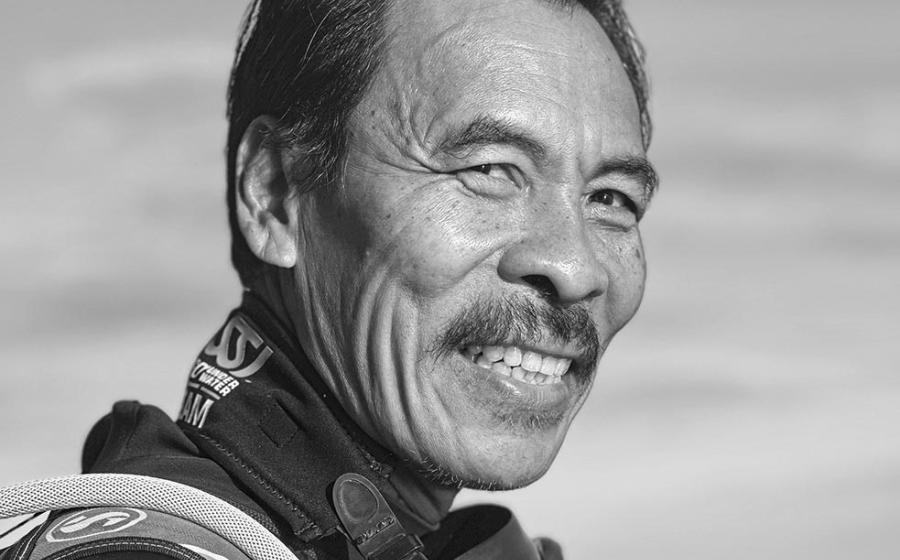

From left to right Donald Gibson, John Nance (CMM), Shawn Gibson, Jo Ann Gibson, and Pat Gotsis discuss how to proceed with the excavation of a 15-million-year-old fossil shark skeleton.Photo courtesy of S. Godfrey

More facts about the find from Dr. Stephen Godfrey:

These sharks have the largest serrations relative to the size of their teeth of any of the many different kinds of fossil sharks known from along Calvert Cliffs. At one time, these sharks were incredibly successful, their fossilized teeth being found around the world in marine sediments. So it is still a mystery as to why this kind of snaggletooth became extinct.

The backbone of the living snaggletooth shark (_Hemipristis elongata) is comprised of 180 vertebrae, including tiny ones that extend to the very end of its tail. There were probably about the same number of vertebrae in the extinct snaggletooth shark. So far, the Gibson family has found about 80. _

S. Godfreyleft: A fossil snaggletooth shark tooth (Hemipristis serra) from the Gibson’s find. It is still partially covered in the reddish-colored ocean-bottom sand that buried the dead shark during the Miocene. right: One of the fossilized spool-shaped snaggletooth shark vertebrae from the Gibsons' backyard. The shark skeleton was so close to the surface that grass roots are visible in one of the openings in the top of the vertebra that held the base of the neural arch.

This Halloween, the Gibson family in Chesapeake Bay, Maryland, had a surprising visit from the dead. While digging a foundation for the construction of his parent’s sunroom, Donald Gibson unearthed the 15-million-year-old grave of a snaggletooth shark. It’s also the most complete fossilized skeleton of the species ever found, including roughly 80 vertebrae and hundreds of teeth.

After the Gibson family called on archaeologists from the Calvert Marine Museum for excavation aid, the unexpected relic was identified as the extinct ancestor to Hemipristis elongata, now native to the Indo-West Pacific ocean region. Also known as the fossil shark, Hemipristis elongata is the only surviving member of the Hemipristis genus and listed as “vulnerable” on the IUCN Red List.

"I really hope that this fossil snaggletooth find will draw attention to the plight of the living snaggletooth shark," Godfrey said. "[Throughout] much of its range, its numbers have been severely diminished by over-fishing."

So how did this 15-million-year-old shark end up so well-preserved in the Gibsons’ backyard? Back when this particular shark was swimming, the Atlantic covered most of the coastal plane. As the Earth changed, sediment from the mountains flowed down rivers that fed into the Atlantic. According to Dr. Stephen Godfrey, Curator of Paleontology at CMM, the shark likely got caught in a storm-driven, underwater sand wave, which protected the shark’s delicate cartilage along with its unique teeth. One tooth is covered in smaller teeth that border both edges.

In December, CT scans will be taken of the skeleton, and for the first time archaeologists will be able to see the true dentition of this shark’s mouth.

"We can associate the size and shape of these snaggletooth teeth with the size and shape of its vertebrae, something that until now has not been possible," Godfrey said.

So, locals got more than just candy for Halloween. Those going by the Gibson residence could see archaeologists carefully extracting seriously rare history.

From left to right Donald Gibson, John Nance (CMM), Shawn Gibson, Jo Ann Gibson, and Pat Gotsis discuss how to proceed with the excavation of a 15-million-year-old fossil shark skeleton.Photo courtesy of S. Godfrey

More facts about the find from Dr. Stephen Godfrey:

These sharks have the largest serrations relative to the size of their teeth of any of the many different kinds of fossil sharks known from along Calvert Cliffs. At one time, these sharks were incredibly successful, their fossilized teeth being found around the world in marine sediments. So it is still a mystery as to why this kind of snaggletooth became extinct.

The backbone of the living snaggletooth shark (_Hemipristis elongata) is comprised of 180 vertebrae, including tiny ones that extend to the very end of its tail. There were probably about the same number of vertebrae in the extinct snaggletooth shark. So far, the Gibson family has found about 80. _