How Do Deep-Diving Cetaceans Avoid DCS?

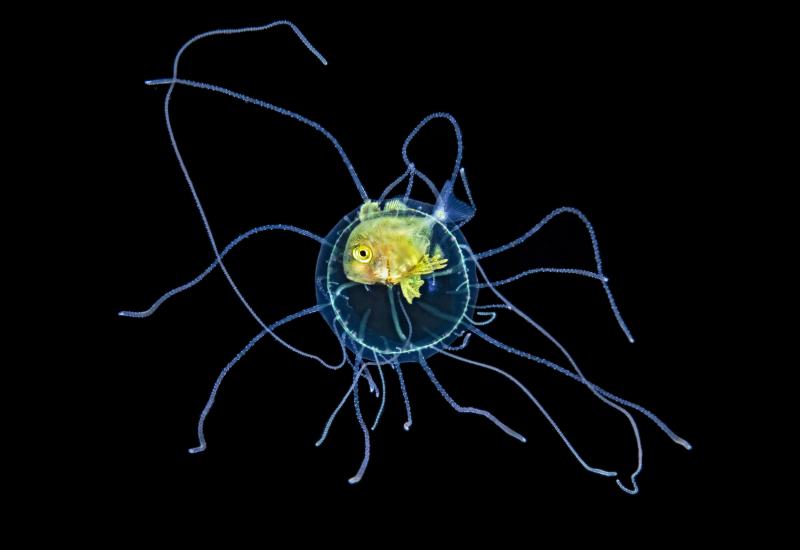

Shane GrossHow do deep-diving cetaceans avoid DCS? Whales and dolphins have a special adaptation that allow them to explore the ocean's depths.

Beaked whales can spend two hours beneath the surface. Dolphins descend down to 1,000 feet and routinely make as many as 20 dives in a row to 300 feet.

Good luck finding that type of profile on a dive table.

So, how do these mammals avoid getting hit with decompression sickness?

Special lung architecture helps protect them from the bends, according to a study by researchers at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Spain’s Fundacion Oceanografic.

When air-breathing animals dive underwater, increasing pressure causes nitrogen bubbles to collect in the bloodstream and tissue. Ascending slowly allows nitrogen to return to the lungs and be exhaled. Ascend too fast, and nitrogen bubbles don’t have time to diffuse back into the lungs. Instead, they begin to expand in blood and tissues, causing pain and damage — DCS, or the bends.

Under deep-sea pressure, the lungs of cetaceans — whales, dolphins and porpoises — create two different regions, one filled with air and one collapsed. This creates a gradient in the amount of blood flow and gas exchange, taking advantage of differences in solubility of oxygen, carbon dioxide and nitrogen.

By the Numbers

9,816: Depth (in feet) of the deepest known dive by a Cuvier’s beaked whale, nine times the depth of the Guinness World Record for the deepest scuba dive in seawater.

90: Approximate number of minutes a sperm whale can hold its breath underwater, while beaked whales can go without a breath for nearly two hours.

1,300: Approximate capacity of a blue whale’s lungs (in gallons), 800 times larger than that of a human.

“These animals have the ability to change that rate,” says biologist Michael Moore, senior scientist at WHOI and a study co-author. “They can manipulate the gradient to favor conditions that transfer oxygen and carbon dioxide but not nitrogen, so as not to increase the risk of DCS. Blood flowing mainly through the compressed region allows absorption of some oxygen while minimizing or preventing the exchange of nitrogen.”

The scientists observed this phenomenon by inflating the lungs from different animals and putting them in a hyperbaric water chamber to simulate dives to different depths. “We compared dolphin, seal and pig lungs, and found dramatic differences,” says Moore. “Terrestrial mammals just don’t have the anatomical and functional adaptations that marine mammals do.”

Marine mammals are not completely immune to DCS, however. Scientists have detected decompression gas bubbles in seals and dolphins that drowned at depth in gill nets. Fourteen dead whales in a 2002 stranding event linked to U.S. Navy sonar exercises had gas bubbles in their tissues — a sign of DCS.

“We know that loud noises are stressful for marine animals,” says Moore. “It can cause a fight-or-flight response, increasing heart rate and vascular dilation. That messes with this protective mechanism — with the way the animal has programmed its dive — and increases absorption of nitrogen in blood.”

The research doesn’t explain why DCS might cause a cetacean to beach, says co-author Andreas Fahlman.

“But just knowing that stress can cause failure of this adaptation means we might find ways to mitigate it,” he says. “The solution could be as simple as starting sonar at low levels so the animals don’t freak out, then increasing levels gradually to give them a chance to move away.”