Ask DAN: Is it Safe to Dive with Stingrays and Sea Urchins?

I’ve always loved being in the water and watching animal documentaries, so I decided to experience the underwater world for myself by taking a scuba diving certification course. I’ve earned my C-card, but I’m a little nervous about coming into contact with marine animals such as stingrays and urchins. Are these animals a serious threat to divers, and could I treat a potential injury?

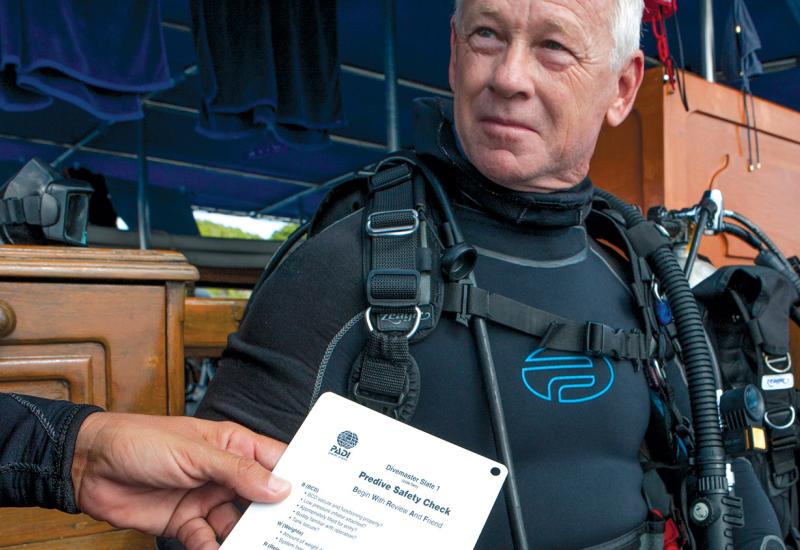

iStockStingrays can injure divers with a serrated barb at the end of their tail that has two venomous glands at its base.

Diving, swimming and even going to the beach offer the opportunity to observe marine animals in a peaceful and familiar environment. Unfortunately, inappropriate interactions with some marine life can lead to serious injuries. The good news is that these injuries are largely preventable, and with some simple forethought and education, water lovers can avoid injuring themselves and the marine life. Accidents do happen, however, and a significant number of divers sustain marine-life injuries every year. Below are best practices in dealing with some of the most common marine-life injuries divers experience.

Urchins

Sea urchins are echinoderms — members of the same phylum of marine animals as starfish, sand dollars and sea cucumbers. They are omnivorous, eating algae and decomposing animal matter, and have tubular feet that allow movement. Most urchins are covered in hollow spines that can easily penetrate a diver’s boots and wetsuit, puncture the skin and break off. Injuries caused by sea urchins are generally puncture wounds, associated with redness and swelling. The pain and severity of injury range from mild to severe, depending on the location of the injury and the compromised tissue, and life-threatening complications do occur but are awfully rare. You can prevent sea urchin injuries by avoiding contact — practice good buoyancy and be wary of areas where sea urchins may exist, such as the rocky entry to a shore dive. Treatment for sea urchin wounds is symptomatic and dependent on the type and location of the injury. Application of heat to the area for 30 to 90 minutes might help. Spines are very fragile, so any attempt to remove superficial spines should be done with caution. Wash the affected area first without forceful scrubbing to avoid causing additional damage if there are still spines embedded in the skin. Apply antibiotic ointment and seek medical evaluation to determine if there are any embedded spines or risk of infection.

Stingrays

Stingrays are frequently considered dangerous or threatening, largely without cause. Stingrays are shy and peaceful fish that do not present a threat to divers unless stepped on or deliberately threatened. The majority of stingray injuries occur in shallow waters where divers or swimmers walk in areas where stingrays may be. Stingrays can vary in size from less than 1 foot to greater than 6 feet in breadth and reside in nearly every ocean on the planet. Injuries from stingrays are rarely fatal but can be painful; they result from contact with a serrated barb at the end of a stingray’s tail, which has two venomous glands at its base. Wounds are prone to become infected, and the barb can easily cut through neoprene wetsuit material and cause lacerations or puncture wounds. Deep lacerations can easily reach large arteries. If a barb breaks off in a wound, it might require surgical care. Treatment of stingray injuries will vary based on the type and location of the injury. Clean the wound thoroughly, control bleeding and immediately seek medical attention. Due to the nature of stingray venom and the risk of serious infections, stingray wounds must be addressed by a professional.

Related Reading: How Your Fitness Impacts Diving

Abrasions

Accidental contact with rocks, corals, wrecks and any number of other hard surfaces can cause injuries. Divers with poor buoyancy in particular frequently come back from a dive with a few more abrasions than when they started. Abrasions can expose divers to microorganisms and increase the risk of infection, as well as cause some bleeding, particularly if damage is done to the skin in a highly perfused area, such as the head, hands or fingers.

How can I prevent abrasions?

You can prevent abrasions by mastering your buoyancy control and using mechanical protection such as gloves, hoods in overhead environments and a full-body wetsuit. Even in locations where thermal protection might not be necessary, a dive skin or thin wetsuit will protect your skin from being exposed and from the potential for cuts and scrapes.

How do you treat abrasions?

If an abrasion is minor, wash the area thoroughly with fresh water and apply an antiseptic solution, then control bleeding with sterile dressings. Afterward, let the area dry and cover it with triple-antibiotic ointment and a sterile bandage. If bleeding can’t be stopped easily, apply pressure to control bleeding and seek immediate medical care.

For more information on first aid and safe diving, visit dan.org/health.