Saving the Sharks With Art

Sharks are older than trees! These ancient predators have dominated our oceans for over 450 million years—long before dinosaurs roamed Earth. Sharks aren’t mindless killers; they’re beautiful, intelligent and essential to our oceans. Some can live for 500 years, reach speeds of 45 mph, have intricate social lives, use their tails to hunt or even glow in the dark.

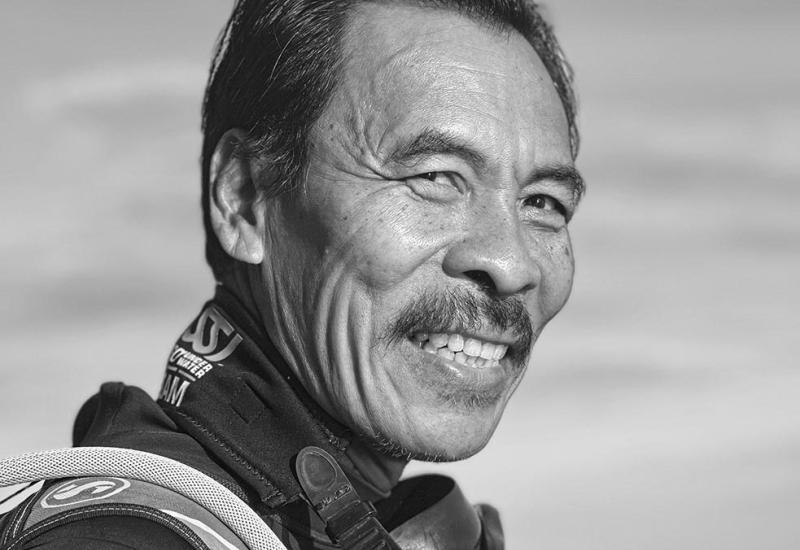

I used to fear sharks, but after a decade of documenting and exploring our oceans through art and storytelling, I have fallen in love with these misunderstood creatures that keep our oceans healthy.

Through my work, I witnessed firsthand a world where chondrichthyans—sharks, rays, skates and chimeras—are exploited and killed for food and as bycatch. It broke my heart. Yet, when I returned home and shared my experiences with my local community, I found that fear dominated their perceptions of sharks. Some even told me, “A good shark is a dead one.”

Related Reading: Conservationist and Retired U.S. Navy Diver Les Burke Named May '25 Sea Hero

That disconnect struck me. Having dived alongside sharks and seen the devastating realities of the shark fishing industry, I realized a crucial problem: People won’t protect what they don’t understand. That realization sparked my journey—a mission to bridge the gap, create connections and inspire people to care about what they once feared.

Through my art, I aim to encourage others to view these ocean guardians in a new light. The misconception that all sharks are like the one in Jaws couldn’t be further from the truth. Each species has unique behaviors, and every species is vital to our oceans.

Every second breath you take comes from the ocean. We need sharks to keep our oceans healthy. If sharks disappear, the ocean suffers, and so do we. It’s estimated that more than 100 million sharks are killed by humans every year. That’s 200 every minute. This fact is what inspired my project’s name: the 200 Sharks project.

The 200 Sharks project is an ongoing social media campaign that combines 200 illustrations of chondrichthyans with videos, storytelling and educational content. Beyond social media, the project includes poster prints and T-shirts, with a portion of sales supporting shark conservation.

I’ve completed about 20 illustrations so far and I expect to finish all 200 in about four years. I create these digital illustrations on my iPad because it allows me to create anywhere. Digital art is also faster than traditional methods. My watercolor paintings can take months to complete, whereas each 200 Sharks illustration takes just two days—a necessity for this timely project.

I select species that need urgent attention and involve my online community in choosing which creatures to highlight.

By the end of this journey, all 200 illustrations will be compiled into the 200 Sharks book—a collection of artwork, facts and stories designed to turn fear into fascination. I hope to win hearts and minds along the way. After all, we protect what we love.

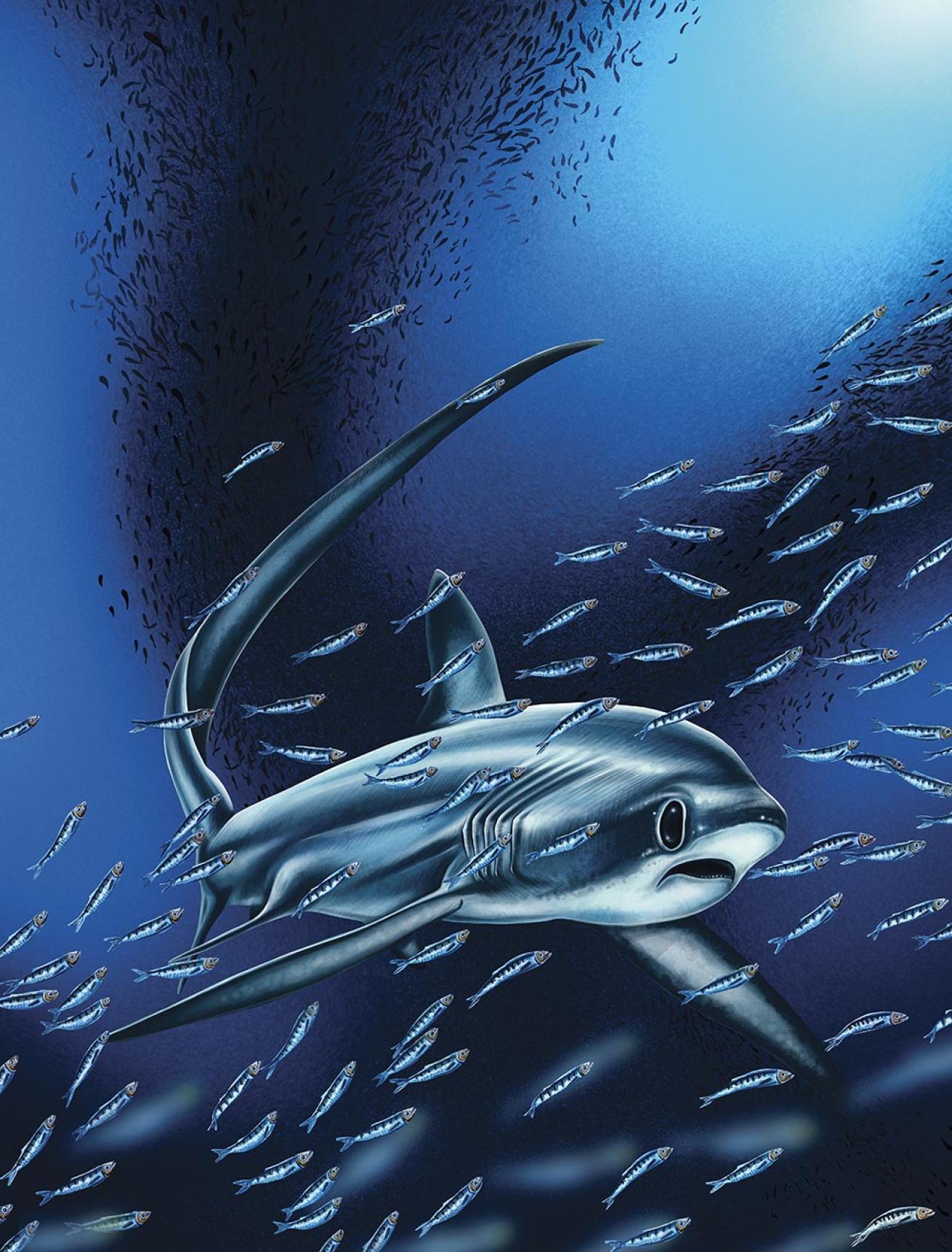

Blue Shark

One of the ocean’s bluest and most charismatic sharks, these nomads of the open ocean are a favorite sight for divers and ecotourism operations. Yet, this shark is also one of the most exploited species. Their fins are in high demand, driving intense fishing pressure, and they often fall victim to bycatch in longlines, which are used to catch many fish, including tuna. Their populations have declined by up to 80 percent in some areas. To help, we can reduce fish consumption, especially tuna caught on longlines, choose sustainably sourced seafood and raise awareness to inspire others to do the same.

Pyjama Shark

Named for their striped “pyjamas,” these sharks are native to the South African kelp forests. By day, they hide under rocks and in caves, emerging at night to hunt fish, crustaceans and octopuses. Their egg cases, known as mermaid’s purses, often wash up onshore. Though frequently caught as fisheries bycatch, they are legally protected from targeted commercial line fishing; as a result, their population is increasing. They are classified as Least Concern by the IUCN.

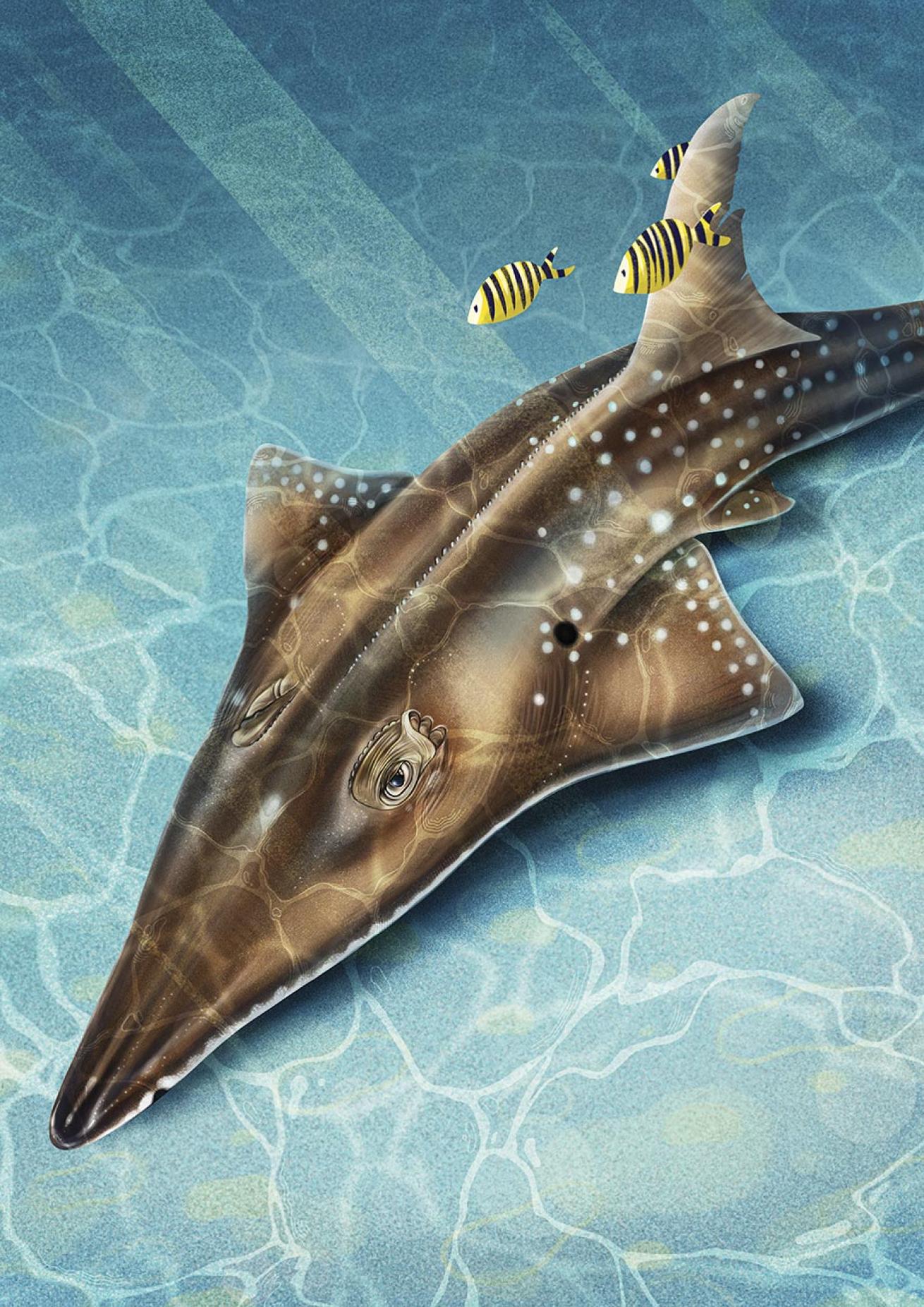

Smoothnose Wedgefish

The wedgefish is a bottom-dwelling, sharklike ray, typically found near the coast in shallow bays and river mouths. Unlike most sharks and rays, it can breathe while stationary by pumping water over its gills. Sadly, its fins are among the most valuable in the international fin trade, fetching hundreds of dollars each. Combined with bycatch and habitat loss, this has pushed wedgefish to the brink, leaving them critically endangered and largely unknown to science. This is a species in urgent need of attention.

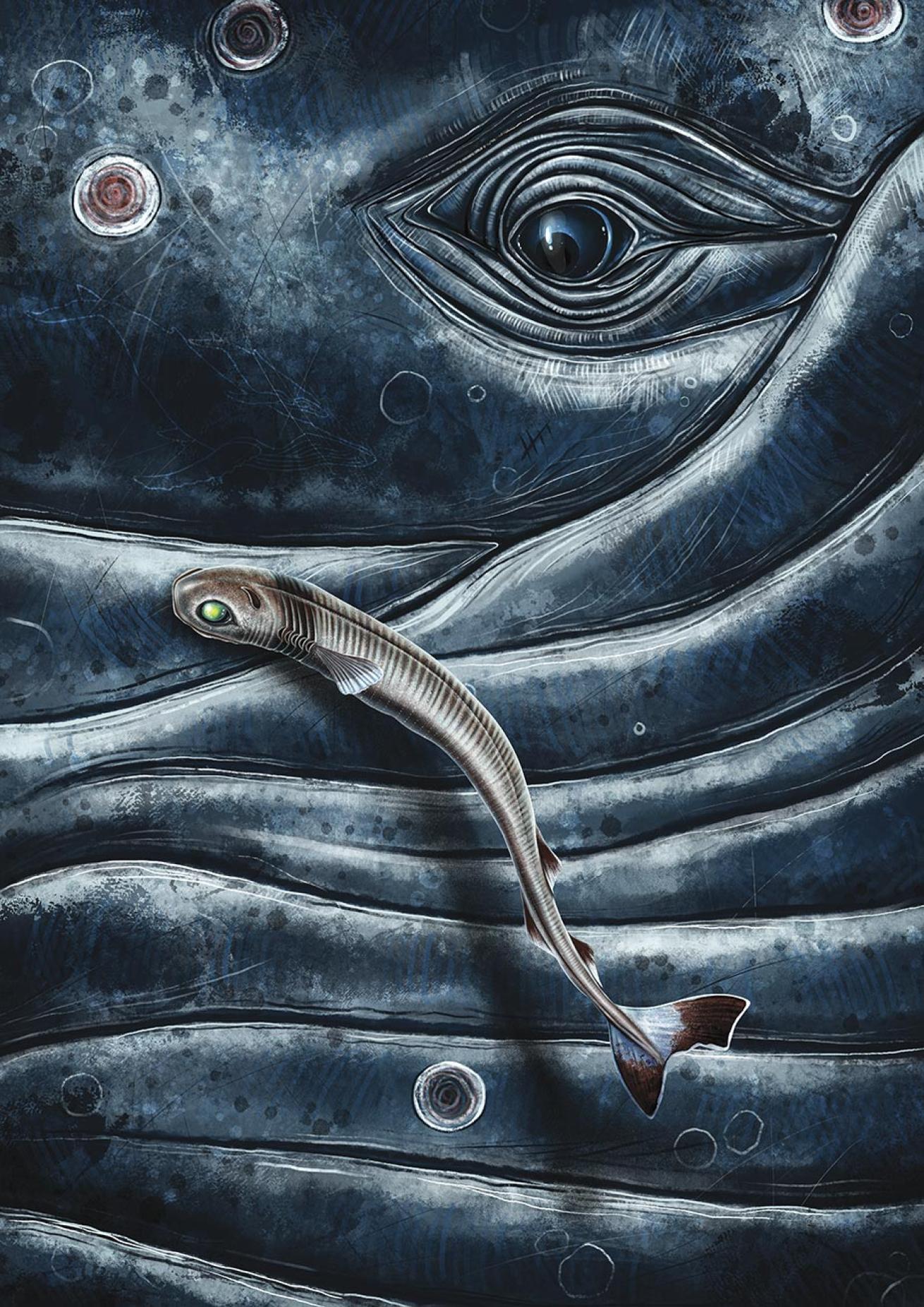

Cookiecutter Shark

This shark has one of the ocean’s most bizarre feeding strategies, taking perfectly round bites out of larger sharks and cetaceans. These deep-sea parasitic sharks even glow in the dark, using bioluminescent light organs to lure in their prey. It sounds like something from a horror movie. However, these little sharks are also helping scientists! Researchers track fresh cookiecutter bites on migratory whales to better understand the whales’ movements and how long they spend in warmer waters.

Pelagic Thresher Shark

Pelagic thresher sharks have incredibly lengthy tails that are as long as their bodies! They use their tails to whip schools of fish and squid at speeds of 80 mph, stunning them for an easy snack. They’re often spotted near drop-offs, narrow continental shelves and seamounts—so keep an eye out when exploring these hotspots. Sadly, they’re at risk of overfishing and habitat loss. Their slow reproductive rates make them particularly vulnerable, emphasizing the need for responsible fishing practices and marine conservation efforts.

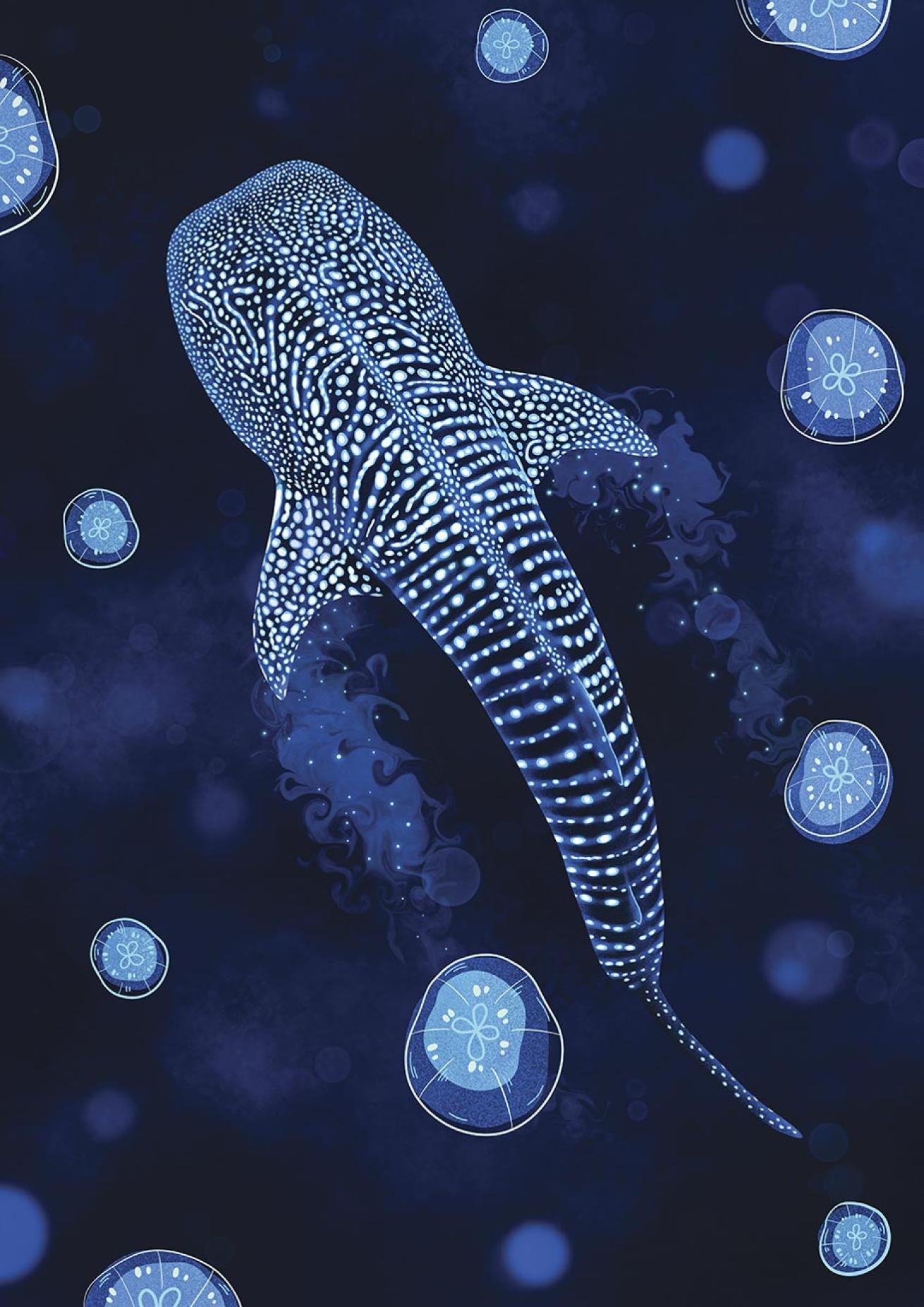

Whale Shark

The whale shark is the largest fish in the ocean and one of only three filter-feeding shark species. Despite their size, they feed on tiny prey, gulping up to 6,000 liters of krill- and plankton-filled water per hour. Their unique spots act like fingerprints, making them one of the most recognizable sharks. Listed as Endangered by the IUCN, their populations have declined by over 50 percent, with bycatch, fishing and vessel strikes being major threats. Whale shark tourism is worth millions of dollars yearly, proving they’re far more valuable alive than in a bowl of soup!

Related Reading: What 50 Years of Shark Surveys Have Revealed

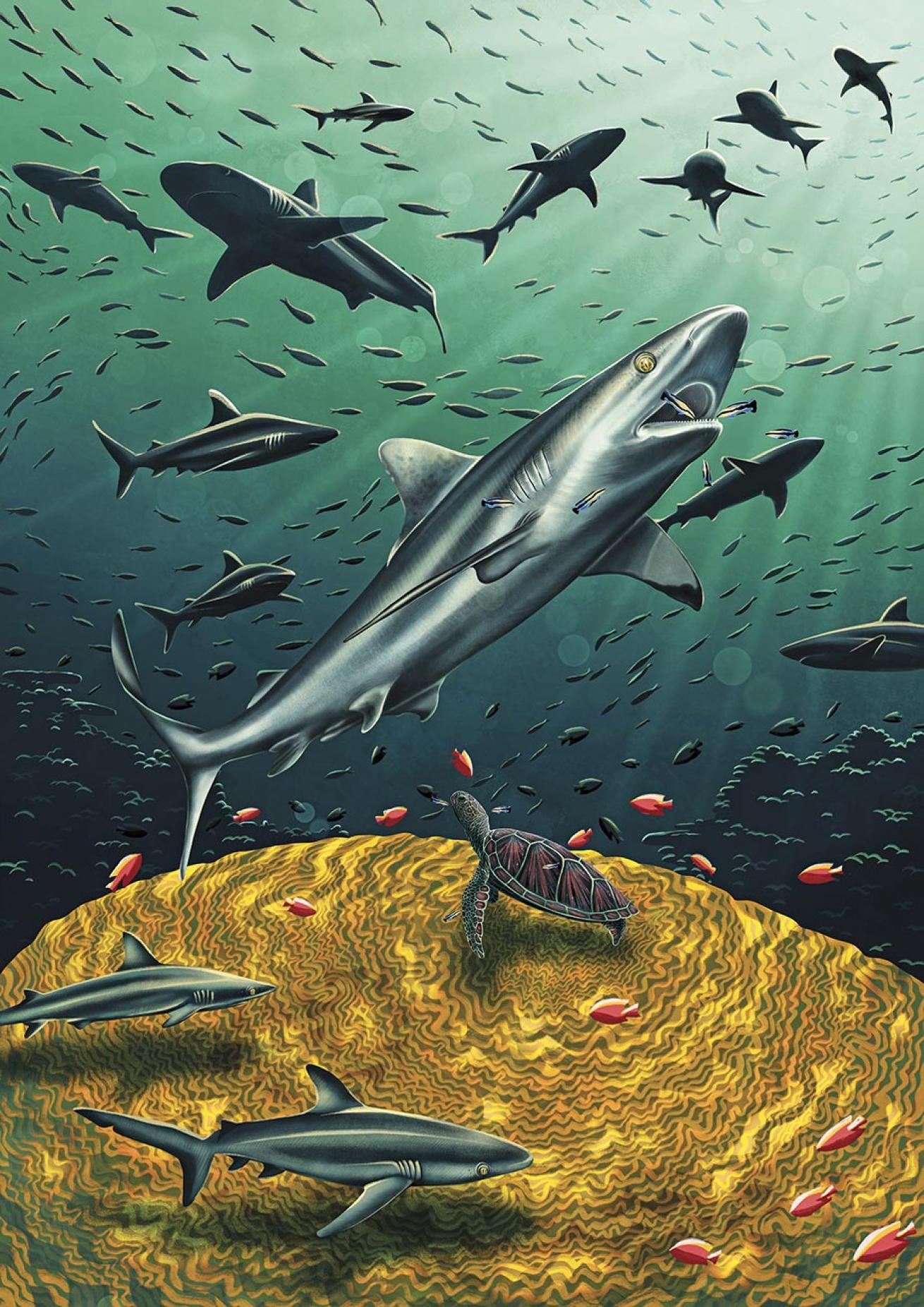

Gray Reef Shark

These strong swimmers are built for life on the move. They produce low-pitched sounds, which scientists believe are used for communication during mating or territorial disputes. These social creatures are threatened by the aquarium trade and unmanaged fisheries, where they are caught for their meat, fins, liver and skin. Closely tied to coral reefs, they are vulnerable to climate change, pollution and destructive fishing. As a key species for dive tourism in places such as Australia, they benefit from protected areas and shark sanctuaries. Their populations are slowly recovering in some areas.