Rediscovering a Passion for Diving in the Seychelles

Shutterstock.com/Will FalconA hawksbill turtle soars over a reef in Seychelles.

A slight movement catches my eye as a stonefish shifts its lumpy form in my periphery. Like a blob of brown curdled cream, it settles back into its nest of algae and coral that clings to The Dredger’s hull. Suspended in 82-degree water, 78 feet beneath the surface, I adjust my mask. I lose sight of him, only to find myself eye to eye with the venomous fish a moment later. His downturned mouth reflects the flicker of anxiety I‘d felt earlier on the boat. I’d recently completed a scuba refresher in the much cooler waters of Cape Town, but this was my first wreck dive in years.

“You’re good with air consumption, right?” Liz Fideria asks me on the boat. With over 7,000 logged dives, Liz is practically a mermaid. She and her husband Gilly run Big Blue Divers in Beau Vallon on Mahé, the largest of Seychelles’ 115 near-pristine Indian Ocean islands. I shrug my shoulders and sheepishly reply “I’m not sure,” wondering if my slight nervousness would reflect in my breathing. She flashes me a reassuring smile just before we roll backward off the boat. My mind wrestles to dispel negative thoughts about what could go wrong and I focus instead on what is in front of me.

Related Reading: Meet the Mountain Mermaid of Appalachia

Elise KirstenThe harbour at Beau Vallon, Mahé, Seychelles.

Courtesy Big Blue DiversA diver explores the exterior of the Dredger.

The Dredger was sunk in 1989 to create an artificial reef. As we near the upturned hull draped in soft coral, I notice a stream of yellowtail snapper (Ocyurus chrysurus). I adjust the mouthpiece of my regulator as the school envelops me, parting like a living curtain.

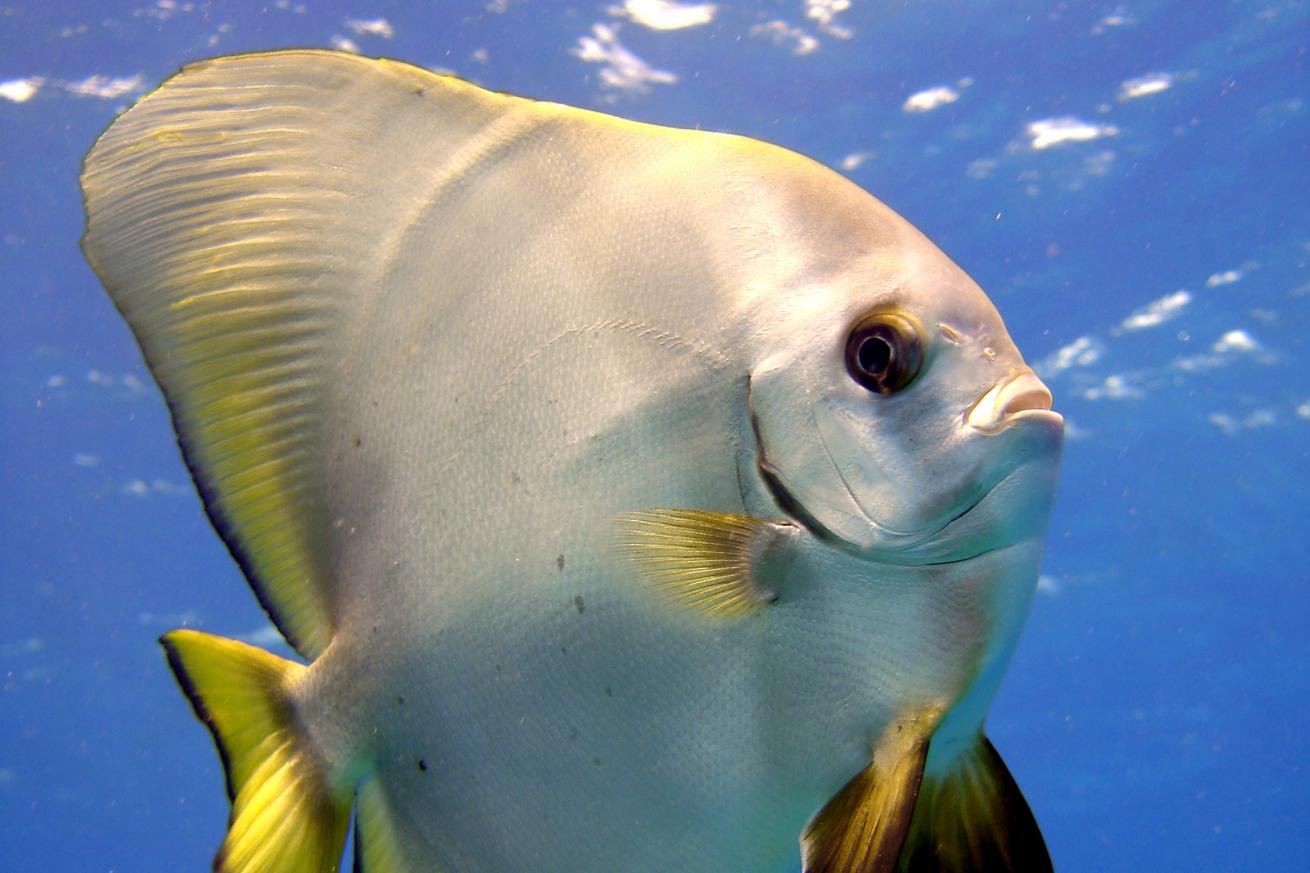

My dive buddy Amanda points out a 3-foot pipefish (Syngnathinae) moving gracefully along the wreck’s edge. A tiny pufferfish (Canthigaster valentini), barely larger than a golf ball, flits spryly between the coral. Longfin batfish (Platax teira) drift through the blue, and blue-spotted red coral groupers (Cephalopholis argus) linger in the shadows, their eyes tracking my movements. I’m enchanted by each creature’s uniqueness and filled with curiosity at what I’ll see next. Finning slowly, I spot another stonefish and realize that the nervous energy I’d felt earlier had dissipated to the sound of bubbles and rhythmic breathing.

Courtesy Big Blue DiversBatfish at the Aquarium, Mahé, Seychelles

Back on the surface for a quick break, Liz offers me sweet vanilla tea. “It’s popular here,” she adds, and I devour the delicious, refreshing treat, feeling grateful as we swap dive stories in the sun before heading to a second dive site known as the Aquarium.

We soon reach the dive site Aquarium, a reef illuminated in bright patterns of turquoise and gold that takes my breath away. We pause for a moment to joyfully observe the electric blue damselfish (Pomacentrus caeruleus) flit over coral gardens. Thirty minutes into our dive, Liz motions to my left. Resting on the reef five feet away is a critically endangered hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata), the first I’d ever encountered on a dive. Seychelles is home to the largest population of hawksbills in the Western Indian Ocean thanks to conservation efforts on islands like Cousin, where the nesting population has grown eightfold since the 1970s, when poaching was a massive threat. I am grateful to have seen one, and to the conservation efforts that make this possible.

Related Reading: Diving in the Georgia Aquarium

Courtesy Big Blue DiversDiver at the Aquarium, Mahé, Seychelles.

Just moments later, something pale and sinuous flickers in the corner of my vision. A small but strikingly white moray eel (Muraenida) with mouth agape reveals the sharp teeth that give its bigger cousins a fearsome reputation. Liz indicates that it’s time to surface. I hover for a moment longer, savouring the final moments of the dive. The feeling of freedom, the peace of the underwater realm and the visual richness of the marine life I’d encountered merge to awaken a passion that had unconsciously faded. I’d forgotten how alive I feel underwater.

Sitting at the stern with a salty tang on my lips and my hair blowing in the wind, I replay the dives in my mind. I’d arrived in Mahé uncertain about my diving ability but determined to take the opportunity to explore this pristine underwater destination. Now, I knew I’d be back. The Seychelles is simply intoxicating. The water is warm, the visibility is great and the fish are as vibrant as a box of colorful jewels. It was like discovering a new favorite flavor of ice cream—you can’t have just one taste.